“His knowledge of military science was excellent. He set clear objectives and checked the execution of his orders in an intelligent and tactful manner. He paid constant attention to his subordinates and, perhaps like no-one else, was able to appreciate and develop the initiative of his subordinate commanders. He gave a lot to other people, but, at the same time, was capable of learning from them… I can’t think of a more thorough, more efficient, hardworking and comprehensively gifted man.” This was how the talented Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov spoke of the no less talented Marshal Konstantin Konstantinovich Rokossovsky, one of the main architects of the USSR’s victory over Nazy Germany.

Konstantin Rokossovsky and Georgy Zhukov.

Evgeny Khaldey/МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruA native of Warsaw (which was then part of the Russian Empire), Rokossovsky began his combat path in the cavalry on the battlefields of World War I. The two revolutions that followed in 1917, the collapse of autocracy and the disintegration of the army and country forced him, like other Poles of the 5th Kargopol Dragoon Regiment, to choose between participating in the creation of a resurgent Poland or dedicating himself to the struggle for the “power of workers and peasants” and the “victory of world revolution”. While Konstantin Konstantinovich’s comrade-in-arms and cousin Franz Rokossovsky left for Warsaw, he himself joined the Bolsheviks.

Konstantin Rokossovsky in 1917.

V.KardashovKonstantin Rokossovsky, however, didn’t end up fighting against his own homeland in the Soviet-Polish War, which broke out in 1919. For most of the Civil War, he fought against the Whites in the Urals, Siberia and the Far East, where he rose to the rank of cavalry regiment commander.

Konstantin Konstantinovch’s successful military career, not to mention his life, could have been cut short during the Great Terror - the period of massive political repression in the Soviet Union in the late 1930s. On August 17, 1937, Divisional Commander Rokossovsky was arrested on suspicion of working for Polish and Japanese intelligence. For two and a half years, he had to drift from prison to prison and endure interrogations until, in March 1940, thanks to the efforts of Army commander 1st rank Semyon Timoshenko, he was released and reinstated in his rank and rights. “He never spoke about it, even with those closest to him,” recalled his grandson (and namesake) Konstantin Rokossovsky. “Only once, when my mother, many years after the war, asked him why he always carried a pistol with him, he replied: ‘If they come for me again, I won’t give myself up alive.’”

In the course of arduous defensive battles against the Wehrmacht in the summer of 1941, Rokossovsky proved himself to be a capable and resolute military commander. With meagre human and technical resources at his disposal, on July 28, he managed to recapture the town of Yartsevo (one of the first liberated Soviet towns) from the Germans, delay the enemy’s advance on Moscow and to ensure that the remnants of two Soviet armies encircled in neighboring Smolensk could escape.

Soviet troops in Smolensk.

Global Look Press“As we fight outside Moscow, we need to think of Berlin. Soviet troops will definitely be in Berlin,” Rokossovsky told a Krasnaya Zvezda [Red Star] newspaper correspondent in October 1941. In that most difficult phase of the battle for the capital, his 16th Army defended the northwestern approaches to the city in the face of a colossal enemy onslaught. Fighting for every meter, his troops halted the Germans and, in early December, took part in the Red Army’s large-scale counter-offensive, which pushed the Wehrmacht 100-150 km away from the city. “It would be difficult to name any other military commander to have operated so successfully in both defensive and offensive operations in the last war… Endowed with the gift of prescience, he almost always unerringly guessed the enemy’s intentions, preempted them and, as a rule, came out triumphant,” recalled Chief Marshal of Aviation Alexander Golovanov.

Rokossovsky was one of the architects of ‘Operation Uranus’ to encircle and destroy the 6th Army of Friedrich Paulus at Stalingrad. In the Battle of Kursk in the summer of 1943, after which the Wehrmacht conclusively lost the initiative in the war, he organized the defences on the north side of the Kursk Salient so skilfully that he deprived German troops of any chance of breaking through. “The troops of the Central Front fulfilled their assignment,” the commander wrote in his memoirs, A Soldier’s Duty. “With their stubborn resistance they sapped the enemy's strength and thwarted his advance… We did not have to draw on HQ reserves and managed without them because we had deployed our forces correctly, concentrating them on the sector that represented the greatest threat to the troops of the front.”

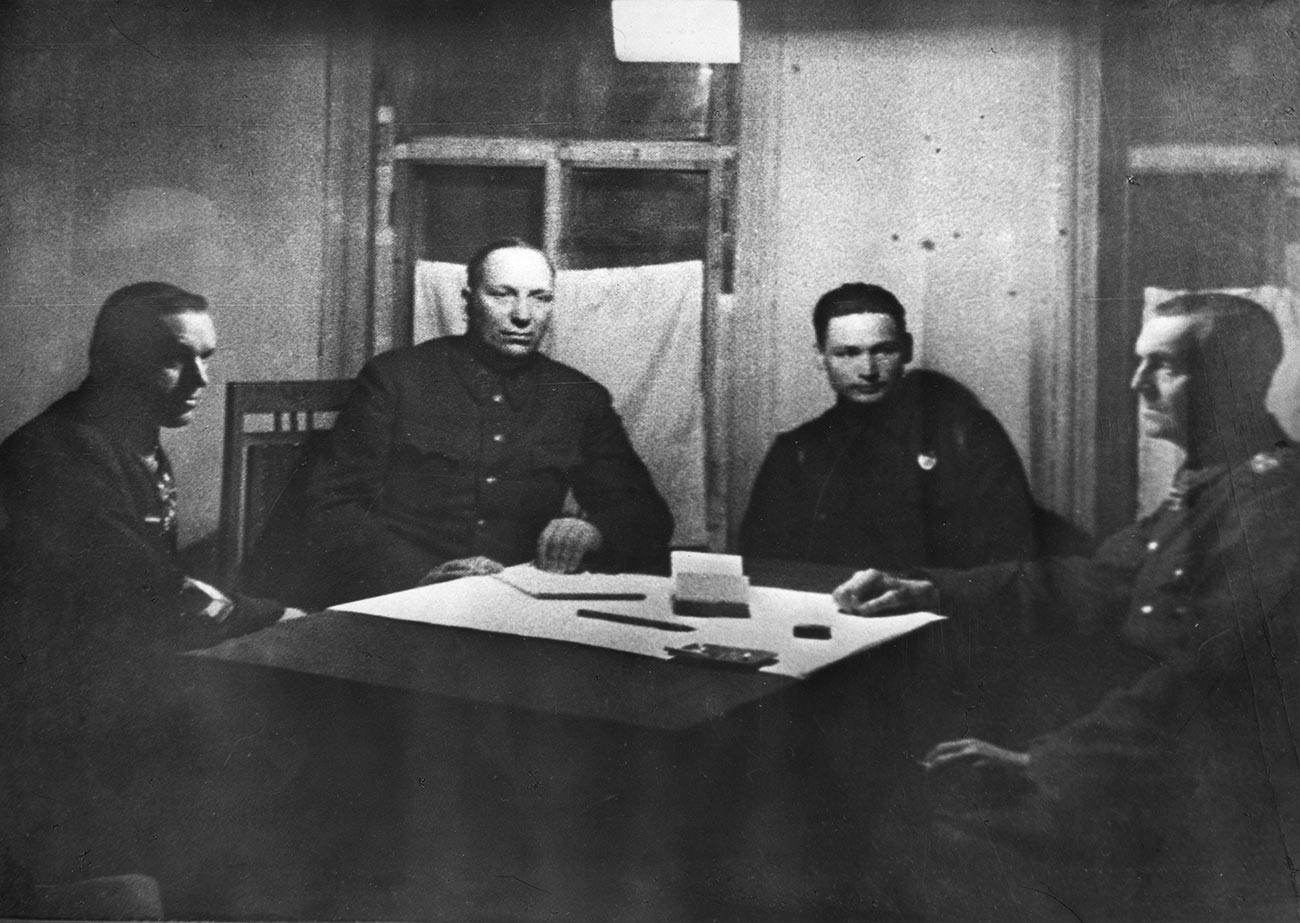

Rokossovsky and Friedrich Paulus.

Sovfoto/Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesIn 1944, Konstantin Konstantinovich was in command of the forces of the 1st Byelorussian Front, which was the main strike force in ‘Operation Bagration’. In just two months of that summer’s “Soviet blitzkrieg”, the Red Army advanced almost 600 km westwards, liberating the entire territory of Byelorussia and part of the Balticsand eastern Poland. The German Army Group Center was completely crushed and the Army Group North found itself with its back to the wall. On June 29, Rokossovsky, whom his enemies dubbed ‘General Dagger’, was given the title of Marshal of the Soviet Union.

In November 1944, when the forces of the 1st Byelorussian Front were ready for a rapid advance into the heart of Germany, Konstantin Konstantinovich was, out of the blue, appointed commander of the 2nd Byelorussian Front. In his memoirs, Rokossovsky recalled a telephone conversation with Stalin: “It was so unexpected that, in the heat of the moment, I immediately asked: ‘Why this disfavor of being moved from the main area of operations to a secondary sector?’ Stalin replied that I was mistaken: The sector to which I was being transferred was part of the overall western area of operations, in which the forces of three fronts would be operating - the 2nd Byelorussian, the 1st Byelorussian and the 1st Ukrainian Front; and the success of this decisive operation will be dependent on the close coordination of these fronts… If you and Konev fail to advance, Zhukov will not advance either,’ the Supreme Commander-in-chief said in conclusion.”

Rokossovsky was more candid in conversation with his close friend, counter-intelligence officer Lt-Gen Nikolai Zheleznikov. “I am the most unfortunate Marshal of the Soviet Union. In Russia, people viewed me as a Pole and, in Poland, as Russian. I was supposed to have taken Berlin - I was nearer than anyone else. But Stalin rang me and said: ‘Berlin will be taken by Zhukov.’ I asked the reason for this disfavor. Stalin replied: ‘It's not a disfavor - it’s politics.’” In the end, the forces of the 2nd Byelorussian Front under Konstantin Konstantinovich’s command smashed the enemy in East Prussia and Pomerania and pinned down the German 3rd Panzer Army, preventing it from taking part in the Battle of Berlin.

Marshal Zhukov, Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery and Marshal Rokossovsky in Berlin.

Public DomainAfter victory, the Marshal temporarily returned to the country of his birth. He commanded the Northern Group of Soviet Forces stationed in Poland. In October 1949, at the request of the president of the Polish People’s Republic, Bolesław Bierut, and with the consent of the USSR leadership, Rokossovsky assumed the post of Polish Minister of National Defence, in which he remained until 1956. Konstantin Konstantinovich was the only Marshal of the Soviet Union in history to be Marshal of Poland, as well.

Konstantin Rokossovsky commands the Victory Parade in Moscow, 1945.

Legion MediaIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox