Russia started to build its own zeppelins even before World War I, but still, most of the Russian airship fleet consisted of adopted foreign models or aircrafts ordered abroad. In 1920, the first Soviet zeppelin appeared - it was an ‘Astra’ airship repaired and renamed as ‘Krasnaya Zvezda’ (“Red Star”). Three years later, an organisation called the Air Center appeared that was tasked with developing the Soviet zeppelins. However, not many successful airships were built. One of the best was the ‘Komsomolskaya Pravda’ (“Komsomol Truth”).

The ‘Komsomolskaya Pravda’ airship.

Pavel Kirukhin/novodevichye.comZeppelin construction became more active after the establishment of the ‘Dirizhablestroy’ (“Zeppelin Construction”) enterprise based at Dolgoprudny (28 kilometers north-west of Moscow) that united everyone connected with airships. Umberto Nobile, a famous aeronautical engineer and Arctic explorer, was invited from Italy and headed the technical management of the organisation. The work at ‘Dirizhablestroy’ resulted in the appearance of eight airships and the biggest of them was a zeppelin with the identification index ‘SSSR-V6’, built in 1934. It was named in honor of ‘Osoaviakhim’ - an organization that worked to improve the defense capacity of the USSR. In general, the construction of the SSSR-V6 was based on the Italian ‘N-4’ airship, but with significant changes according to the previous Soviet airship experience. The SSSR-V6 was 104.5 meters long and 18.8 meters in diameter - much bigger than any previous Soviet airship and could carry up to 8.5 tons of cargo. The first flight of ‘Osoaviakhim’ took place on November 5, 1934. Umberto Nobile commanded the crew himself. This flight lasted one hour and 45 minutes. Other test flights had also proved that the airship was good enough to be regularly used.

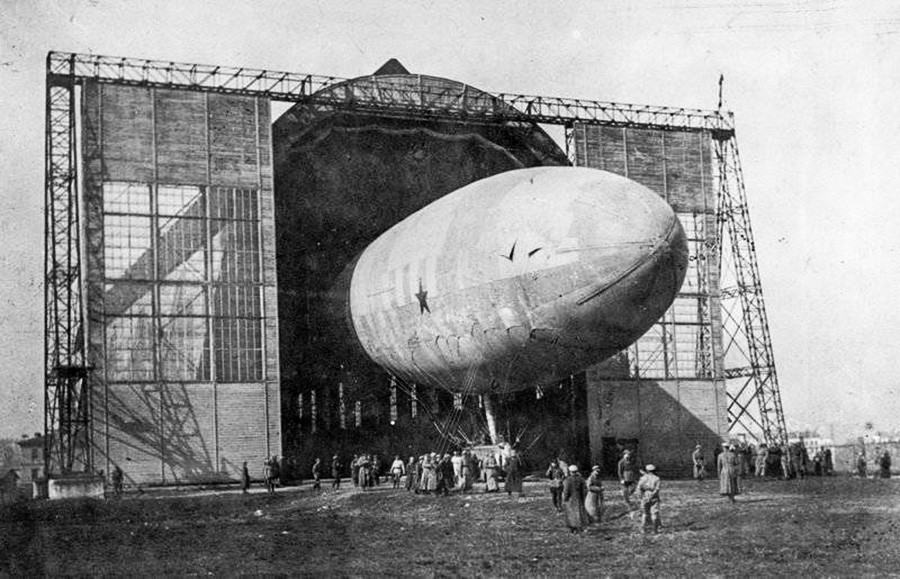

The inflation of SSSR-V6 hull.

Pavel Kirukhin/novodevichye.comAt the same time, the zeppelin industry didn’t develop much, in comparison with the airplane sector. For example, in 1937, airplane pilots set 23 different records (including the legendary flight of Valery Chkalov), while the aeronauts had absolutely nothing to boast about. All the enthusiasts understood that they had to perform something remarkable to save the industry. They chose the SSSR-V6 to try to set a record and figured out that the best thing the airship could perform was the longest flight without landing and refueling. The German LZ 127 ‘Graf Zeppelin’ airship held the record: It spent 119 consecutive hours in the air in 1935.

SSSR-V6 ‘Osoaviakhim’ airship.

Public domainThe preparations took two weeks. All the instruments and the airship itself were thoroughly checked, the hull was filled with fresh gas and varnished. The flight started on September 29, 1937, at 6:48 a.m. The 16 crew members didn’t actually have a task to set a record, they were just told to fly as long as they could. Their route was planned previously and was 2,800 kilometers long. The aeronauts had to fly over several big cities like Novgorod (now Veliky Novgorod, 490 kilometers north-west of Moscow), Kazan (720 kilometers east of Moscow) and Kursk (460 kilometers south-west of Moscow). Ivan Pankov, the crew commander, remembered later that at the beginning, the SSSR-V6 rose to an altitude of 100-150 meters, because it was overloaded with 5.7 tons of fuel. To mark their way, the crew had to throw down message bags (small containers with parachutes) when they reached appointed places like Novgorod.

The following day, the aeronauts got into a cyclone. Pankov told Soviet journalists it was the hardest part of the route: the zeppelin went through thick clouds and under heavy rains for 20 hours. On October 1, the crew changed the route and turned a little to the west to get out of the bad weather. There is also an unsubstantiated rumor that the aeronauts had just lost their way, due to radio-compass failure. Nevertheless, they didn’t reach Kazan and, instead, headed to Ivanovo (250 kilometers north-east of Moscow).

SSSR-V6 in the sky above Moscow.

Pavel Kirukhin/novodevichye.comAfter the cyclone, the crew didn’t meet any new difficulties and, on October 3, reached Vasilsursk (520 kilometers east of Moscow) - the settlement where they were to turn and head directly back to Moscow and finish the flight. After more than 100 hours of the flight had passed, the crew understood their task was fulfilled, but they had enough resources to continue and ground control let the SSSR-V6 spend an extra 24 hours in the air and land on October 5 at 5 p.m. This is why the crew turned from Moscow to Vladimir (180 kilometers north-east of Moscow), then came back and landed at approximately 5:15 p.m. So, the flight of SSSR-V6 lasted 130 hours 27 minutes - a new world record. However, the Soviet administration was quite sceptical about this achievement: the crew was only awarded with some money and the airship industry didn’t receive any extra financing.

The SSSR-V6 crew after the flight.

Pavel Kirukhin/novodevichye.comAfter its triumph, the SSSR-V6 ‘Osoaviakhim’ continued operating. At the beginning of 1938, the airship was going through preparations for a flight to Novosibirsk (2,800 kilometers east of Moscow), but this plan was suddenly cancelled. A group of four Arctic explorers, headed by Ivan Papanin, got into trouble in the Arctic Ocean: they were manning a polar station on a drifting ice floe, which had suddenly cracked. Icebreakers were sent to save the explorers, but some members of SSSR-V6 crew on February 4 wrote a letter to Joseph Stalin asking to let them try to fly to Murmansk (1,500 kilometers north-west of Moscow) and then to the polar station to get to the explorers faster than the ships. The proposal was accepted and, on February 5, the SSSR-V6 with 18 people on board started the journey which would soon turn into a tragedy. The following day, the airship lost its way, hit a mountain called ‘Neblo’ and caught on fire near the town of Kandalaksha (200 kilometers south-west of Murmansk). Thirteen crew members died. The others got away with minor injuries and were soon rescued from the crash site by locals.

The monument at the place of the crash.

Pavel Kirukhin/novodevichye.comViktor Pochekin, the fourth officer and the catastrophe survivor, recalled that on February 6, the airship flew into heavy snow and clouds. At 7:30 p.m. Georgy Myachkov, the navigator, cried that a mountain was in front of SSSR-V6. Ivan Pankov, the second commander, steered the zeppelin upward to gain altitude, but it collided and a fire started. The results of an official investigation said that before the crash, the airship was going at an altitude of 300-350 meters, while the Khibiny Mountains located in that area are more than a kilometer high. Also, the idea of Pankov to steer upward was wrong - the crew should have thrown out all the dry load to gain altitude faster. At the same time, the bad weather and darkness let Myachkov see Neblo just about five seconds before the crash. The investigation commission also considered the crew wasn’t well prepared, either: For example, Pochekin (one of the enthusiasts of the journey) confirmed during the interrogation that he only found out he had been chosen for the flight on departure day. All these problems led to the catastrophe.

The burial site of SSSR-V6 ‘Osoaviakhim’ crew at Novodevichy Cemetery.

Pavel Kirukhin/novodevichye.comIvan Papanin’s team was saved on February 19, but the Soviet airship industry died with the SSSR-V6. Only a couple of zeppelins were built after the tragedy. And, in 1940, the Soviet administration found the airship industry to be futureless and shut the program for good.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox