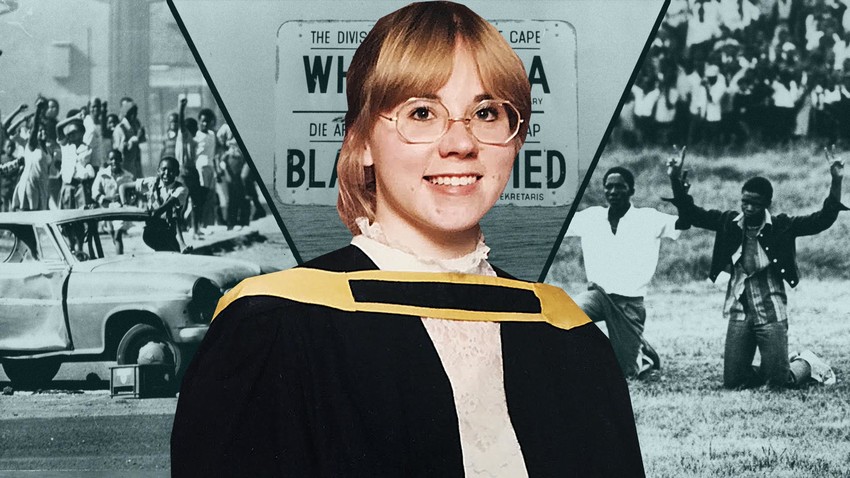

Recruited as a young woman by Nelson Mandela’s National African Congress to spy on the South African apartheid regime, Sue Dobson quickly rose up through the ranks and established contacts with the leading figures of the white minority government. Little did she know that her cover would soon be blown and she would need to employ all her skills — acquired in the USSR — to stay alive and free, against the odds.

Sue Dobson’s incredible story — which inspired a soon-to-be-released book and a movie — begins in South Africa of the early 1980s, a country where the minority rule ruthlessly enforced the existing apartheid regime and did away with those who dared to resist.

South African police beating Black women with clubs after they raided and set a beer hall on fire in protest against apartheid, Durban, South Africa.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesThrough her sister-in-law, 20-year-old Sue Dobson, an offspring of a privileged white South African family, a trustworthy graduate of a white-only school, entered the ranks of the National African Congress, a social-democratic political party that was outlawed in South Africa at the time.

While inside, she was recruited into the intelligence branch of the party and sent off to the Soviet Union to hone her military and intelligence skills.

“I was recruited into the ANC and I met with the head of military intelligence Ronnie Kasrils. He recruited me and suggested military training in what was then the USSR. My brief was to be trained in the Soviet Union and then to return to South Africa, where I would work undercover in a position that was close to the government. Which was exactly what I did,” said Dobson.

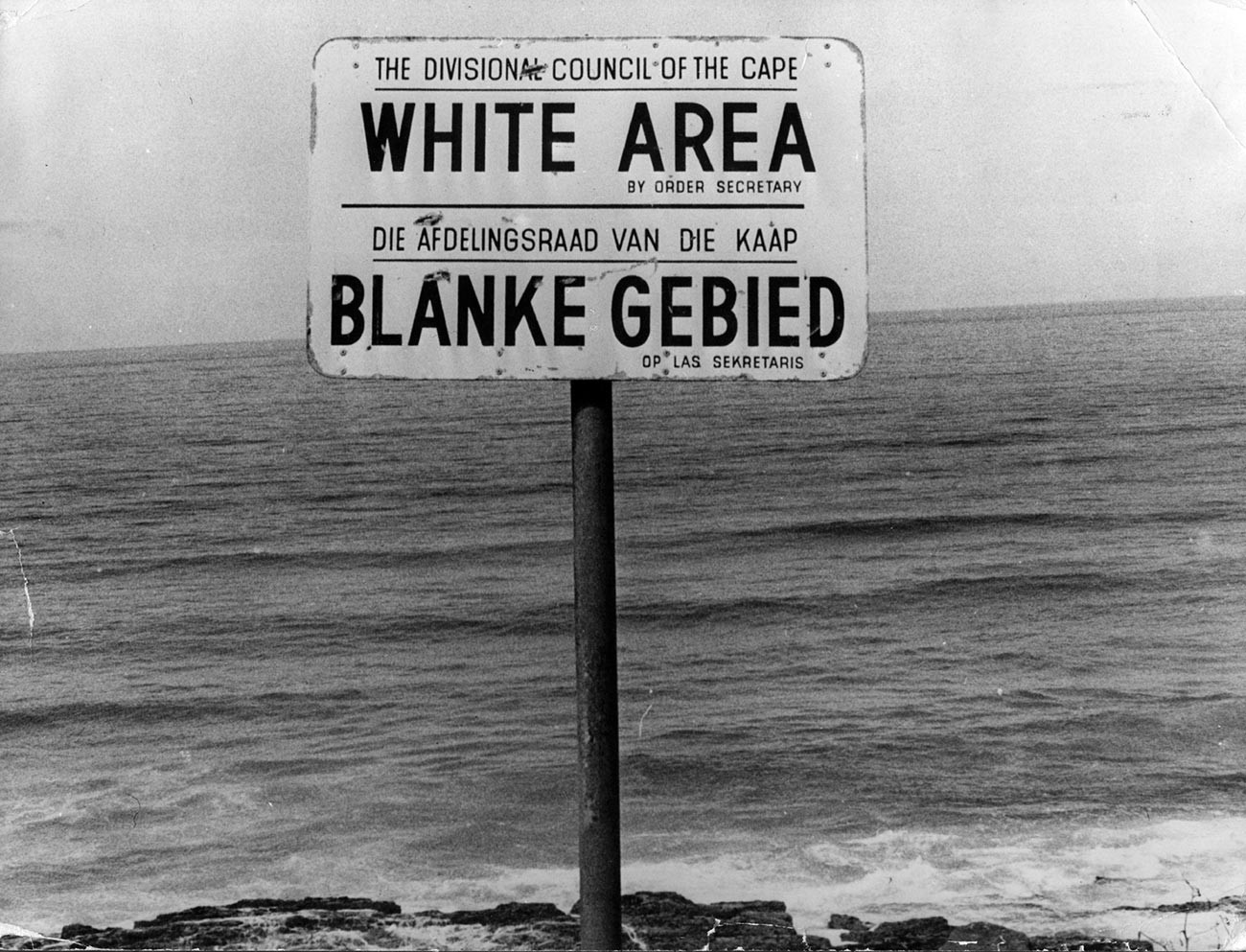

An apartheid notice on a beach near Capetown, denoting the area for whites only.

Keystone/Getty ImagesTo leave her country for months, Sue and her husband needed to develop a solid alibi as to not raise alerts back home.

“The plan was very carefully thought out. We had a legend where we told family and friends that we were going backpacking through Europe and that we were going to be away for approximately one year and after that we would return to South Africa and settle down. We collected as many postcards from as many destinations as we could. And we wrote those postcards and they were posted by Soviet officials in various Western European countries and sent home to South Africa so that it looked like we sent the postcards to friends and family from these destinations while we were in Moscow having our training,” said Dobson.

After the preparation phase was complete, the young woman and her husband were ready to head off.

In Autumn 1985, the couple landed at Sheremetyevo Airport in Moscow, the capital of the Soviet Union, a leading country of the socialist block that, at the time, proclaimed itself a champion of racial equality. In the midst of the Cold War, this meant the USSR would support the ANC, not only because of the party’s struggle for racial equality in South Africa, but also because helping to end the anti-Soviet white majority rule in the country would potentially empower Moscow to establish an important Cold War stronghold on the African continent.

But, for 20-year-old idealistic Dobson, who wholeheartedly believed in the ANC cause, the Soviet Union appeared like the promised land where racial equality and social justice reigned.

“We have been taught [in school] that the Soviet Union was something very different, that it was very bad. And I was astonished at just how ordinary it was and how beautiful the streets were. It was a time of perestroika and glasnost and Gorbachev was very popular at the time. It was quite interesting to see ordinary people in the streets demonstrating for peace and that was something that I have never seen before. At the time, it offered me a view of humanity that I had not seen before.” said Dobson.

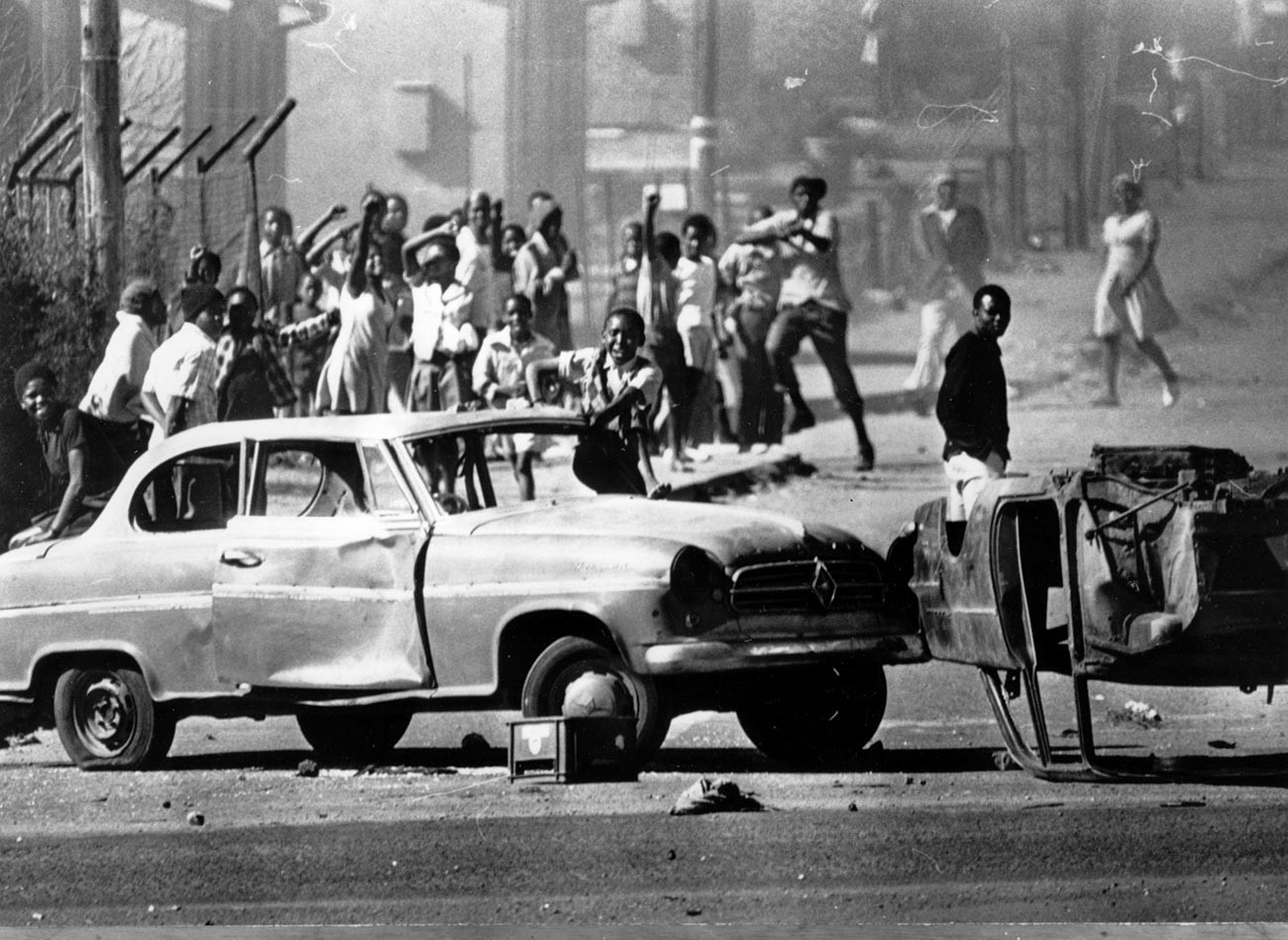

South African rioters in Soweto use cars as roadblocks during unrest stemming from protests against the use of Afrikaans in schools.

Keystone/Getty ImagesThe woman was so impressed with what she saw that she said she identified herself as a communist at the time.

“Since the fall of the Soviet Union and disintegration of the Eastern Bloc, there were a lot of things that people reconsidered. And some things are better in theory than they are in practice and we don’t necessarily know that. But, coming from a situation such as mine, I fervently believed the USSR offered a better alternative for the people of South Africa than what they had at that point in time. I think I would describe myself as a communist,” said Dobson.

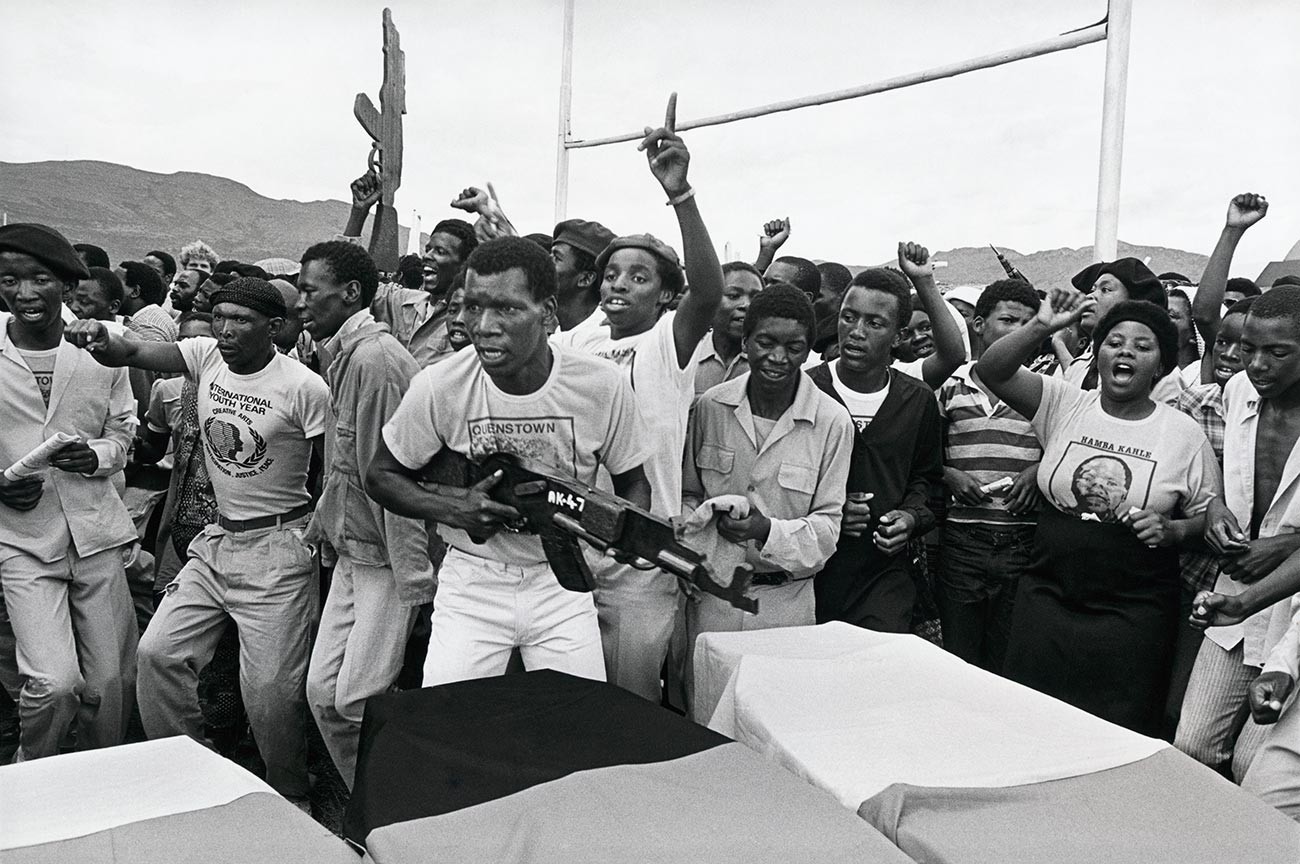

Mourners brandish replica wooden guns and sing in support of the banned African National Congress at the funeral of ANC militants killed in Queenstown, South Africa.

Gideon Mendel/Corbis/Getty ImagesImmediately after arrival, Dobson and her husband were quartered in a safe house on Gorky Street (currently Tverskaya Street), a stone’s throw from the Kremlin and the Red Square. For the next seven months, the couple would undergo extensive military and intelligence training led by Soviet instructors and aimed at honing the espionage and survival skills of the undercover ANC agents within the South African government.

“As my training progressed, it was important for me to pick up surveillance and counter-surveillance. It was important to understand how to pick up surveillance on foot, in a car, how surveillance teams change. There would be a surveillance team of maybe five or six people and my task would be to find those using as many techniques as possible: crossing a road, stopping suddenly to ask somebody time and see who’s behind you, getting on and off public transport. There were a lot of things taught to make you more vigilant. There were also explosives training, radio work, political instruction, weaponry — it was a well-rounded course. Later on, those things actually saved my life,” said Dobson.

When it was time to leave Moscow behind, Sue Dobson returned to her native South Africa as a trained agent. Little did she know, the skills and contacts she gained during her stay in the Soviet Union would soon come in handy when her cover would be blown.

Upon returning to South Africa in 1986, Dobson worked for a Pretoria-based newspaper, before she was employed by the government’s information bureau, where she gained invaluable insights into the South African government plans. For example, to discredit the SWAPO Party of Namibia.

Despite her rising importance as the ANC intelligence asset, Dobson was never provided an escape route in case her cover was blown.

“It was up to me and my handler to establish a safe route, to create a plan B. Unfortunately, that was never forthcoming, because Ronnie [Kasrils] never provided that. That was a shortcoming. I didn’t have any papers, I had no money, I had no documents, no safe houses, nowhere I could take refuge. That was a serious failing on part of my handler and my organization. That should not have been allowed to happen,” said Dobson.

Working as the ANC undercover agent in the ranks of the information bureau, Dobson gained access to members of parliament and ministers. Eventually, the young professional, who did not raise suspicions, was being considered for a post in the office of president FW de Klerk, a dream job of any ANC intelligence agent. The high office required another level of security clearance and a more thorough background check, however, which revealed the woman’s link to the ANC. Sue Dobson was “burned”, meaning that she had been exposed as a spy.

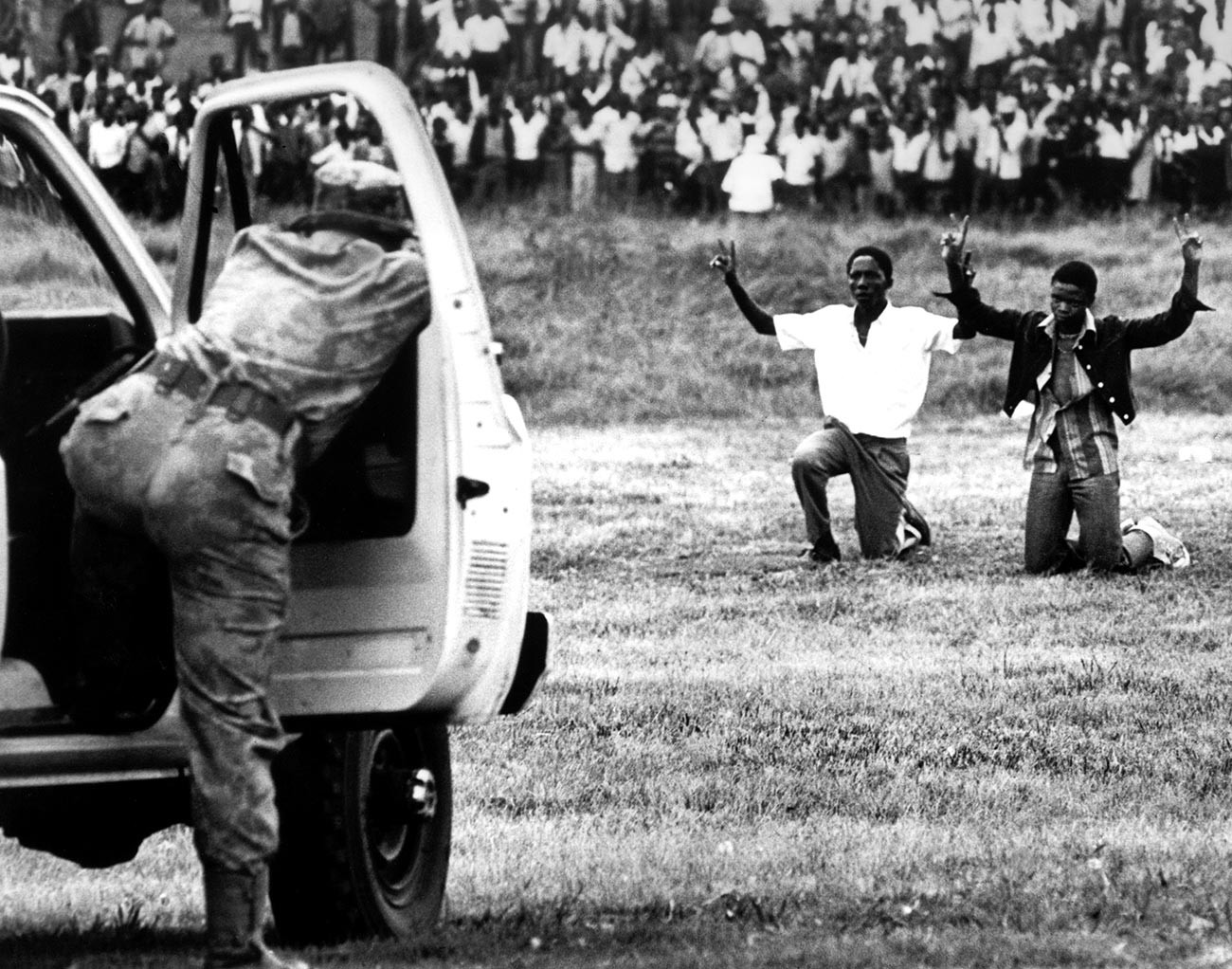

Soweto youths kneeling in front of the police holding their hands in the air showing the peace sign on June 16, 1976, in Soweto, South Africa.

Jan Hamman/Foto24/Gallo Images/Getty ImageCornered and left on her own against the whole might of the government, the woman had no other choice but to go all-in. She had to escape South Africa and reach the Soviet Embassy in neighboring Botswana, as she reasoned it was the only place where she could get help.

“I had to get myself out of a very difficult situation. If I hadn’t had the training, I probably wouldn’t have been able to do it. I was actually working in Namibia at the time when I realized my cover was blown. I needed to get into exile as quickly as possible, in order to save myself. But I couldn’t take a flight, as they would be expecting me to take a flight from Namibia to Europe. What I did was hire a car and actually drove the distance, which was something they didn’t anticipate me doing. I suppose what the training in the USSR did was it taught me to think out of the box,” said Dobson.

When the escapee arrived in Botswana, she suddenly noticed a tail and realized it was only a matter of time until the agents of the South African government would make a move to apprehend her.

“I knew I was under surveillance. I was arriving in Gaborone when I picked up the tail. There was a South African car on my tail. I realized it was probably getting close to a point where they would probably make the arrest. I managed to get to a hotel, a Holiday Inn in Gaborone. I got a room, went upstairs, checked surveillance, noticed that the car was parked in the parking area, along with mine. I realized then I didn’t have much time. I picked up the telephone directory and I looked for the number of the Soviet mission, bearing in mind there was no plan B. I had no instructions about what to do if things went bad. It was late in the evening. I took the chance and just hoped that somebody would answer. And they did.”

“I greeted them in Russian. I explained who I was, I explained about the danger and then said, ‘Please, could you help me, because no one else has been able to help me?’ The man on the phone said, ‘Meet me downstairs in 20 minutes.’ That’s what I did. I went out of the back entrance of the hotel and waited. A car came up to me and somebody told me to get in. I had no idea if it was him, I was taking the absolute risk. He identified himself and I heard his accent. He was Russian. Then he drove me to the Soviet compound in Gaborone,” said Dobson.

Dobson stayed inside the Soviet compound for a few days before the Russians put her on a plane to London.

“They got me on a flight to the UK. But it was right at the last minute. Just before the gate closed, they rushed me through. There was some arrangement with airport security. I remember my Russian friend speaking to the man at the gate and they beckoned me through. I managed to get to the UK safely,” said the woman.

Dobson said she picked London as her destination, because the location had been previously discussed with her handler. Had she been offered asylum in the Soviet Union, she might have reconsidered.

“I would have been very tempted to go to the USSR.”

Sue Dobson“I supposed I was geared to go to the UK, but if the invitation had been made, I would have been very tempted to go to the USSR,” she said.

Today, Sue Dobson lives a quiet life in the UK. Although she did visit her native South Africa when it was safe for her, she never had a chance to return to Moscow or personally thank her instructors and the Soviet diplomat who had come to her rescue years ago in Botswana. The woman hopes that in publicizing her story the words might reach their destination.

"I would have loved to go back. I would still love to go back."

Sue Dobson“I want to say thank you to those people who trained me, who looked after me and who saved me. Because they made such a difference to my life. I wouldn’t have been able to do the things I’ve done or have a life I’ve had without those people. I’m immensely grateful to them.”

Soon, however, Sue Dobson’s story will finally be told, both in book and film format. The woman believes this will be an important contribution to the history of South Africa. As to her feelings for Russia, Sue Dobson still loves the country which played a crucial role in her life, however short her stay in Moscow was.

“I would have loved to go back. I would still love to go back.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox