In June 1945, the Soviet Union was at the peak of its power: Nazi Germany had been defeated, the whole of Eastern Europe was firmly inside Moscow's sphere of influence, and the Red Army, the strongest in the world at the time, was preparing to enter the war against Japan and deliver a decisive blow.

In these circumstances, the Soviet leadership believed it was high time to exert diplomatic pressure on Turkey, with which it had a number of important military, political and territorial disputes. The Soviets’ newfound authority and enormous influence, as well as the fact that the Western allies desperately needed Soviet help in the war against the Japanese, convinced Stalin that dealing with Ankara would be like taking candy from a baby. Subsequent events proved otherwise.

Turkey's policy during WWII had provoked highly contradictory feelings in the Kremlin. On the one hand, Ankara’s proclaimed neutrality and refusal to let the Wehrmacht through its territory were welcomed by Moscow in every conceivable way.

On the other hand, in the darkest days of the Soviet-German confrontation, the Turks maintained a large grouping of troops on the USSR’s southern border. In the fall of 1941, at the invitation of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, Turkish Army Generals Ali Fuad Erden and Hüseyin Hüsnü Emir Erkilet visited the occupied Soviet territories.

The Kremlin believed that in the event of the defeat of the Red Army, and the fall of Moscow and Stalingrad, the Turks might invade the Soviet Caucasus. “In mid-1942, no one could guarantee that [Turkey] would not side with Germany,” wrote General Semyon Shtemenko in his memoirs. To repel a possible attack required forces that were urgently needed elsewhere.

Turkish Army Generals Hüseyin Hüsnü Emir Erkilet and Ali Fuad Erden in the USSR.

Public DomainMoreover, the USSR was convinced that Ankara had repeatedly violated the 1936 Montreux Convention regarding the status of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles, turning a blind eye to Kriegsmarine auxiliary warships entering the straits under the guise of merchant vessels. The question of Turkish sovereignty over the straits had vexed Stalin even before the war; now in 1945 he had the opportunity to address it.

Moscow was readying itself for a diplomatic conflict with Turkey, which the latter’s joining the anti-Hitler coalition on Feb. 23, 1945, did nothing to avert. In March of that same year, the USSR denounced the Soviet-Turkish Treaty of Friendship and Neutrality of 1925, and on June 7 the Turkish ambassador to the USSR, Selim Sarper, was summoned to a meeting with People’s Commissar (Minister) of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov.

Soviet border guards near the Turkish border in 1940.

Dmitry Debabov/SputnikThe Turkish side was notified that, since Ankara was unable to exercise proper control over the straits, henceforth they would be overseen jointly with the Soviet Union, whose navy would be provided with several bases in the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles.

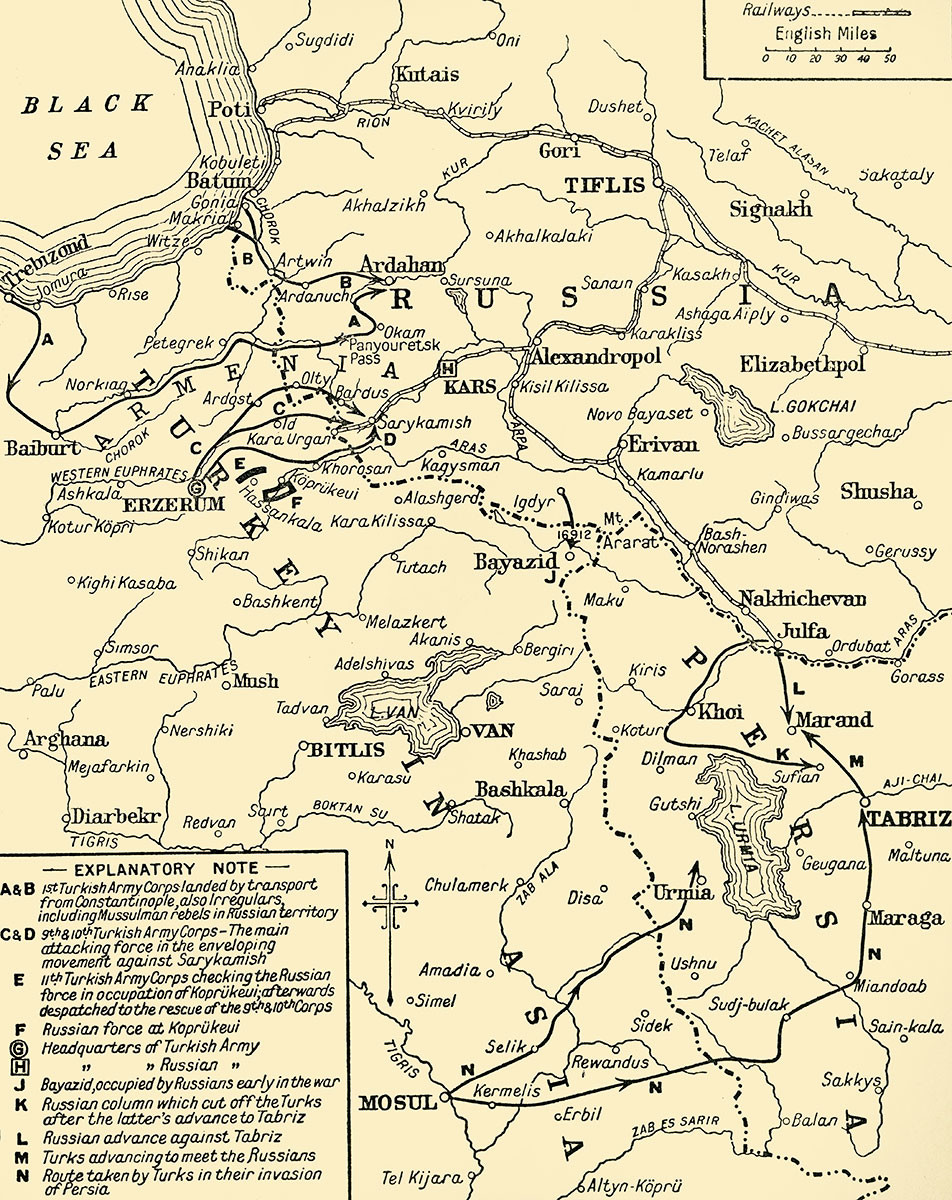

In addition, the USSR insisted on revising the Treaty of Moscow of 1921, by which the Bolsheviks had transferred to Turkey the cities of Kars, Ardahan and Artvin, plus the extensive surrounding territories, which had previously belonged to the Russian Empire. Since the governments of Lenin and Kemal Ataturk had been on friendly terms and jointly opposed the Entente, this concession was then regarded in Moscow as an important and timely step toward building a strong, long-term alliance.

In the late 1940s, however, the USSR viewed the situation through a very different lens. The Soviet press wrote about the “treachery of the Turks,” who had taken advantage of the weakness of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Caucasian republics, about the “forced removal” of small indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands, and about the need to reunite Soviet Armenians and Georgians with their brothers on the other side of the border. “There are no reasonable arguments against the return of these territories to their rightful owners, the Armenian and Georgian peoples,” stated the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs in a report for the country’s leadership in August 1945.

A Turkish officer inspects his soldiers at the Soviet-Turkish border.

Getty ImagesMoscow’s pressure provoked a sharp rise in anti-Soviet sentiment in Turkish society. Stalin was branded the “heir of the Russian tsars,” who for centuries had sought to seize the Black Sea straits. “The leaders of the Red order are the continuation of the Romanovs,” declared the Mejlis, the Turkish legislature.

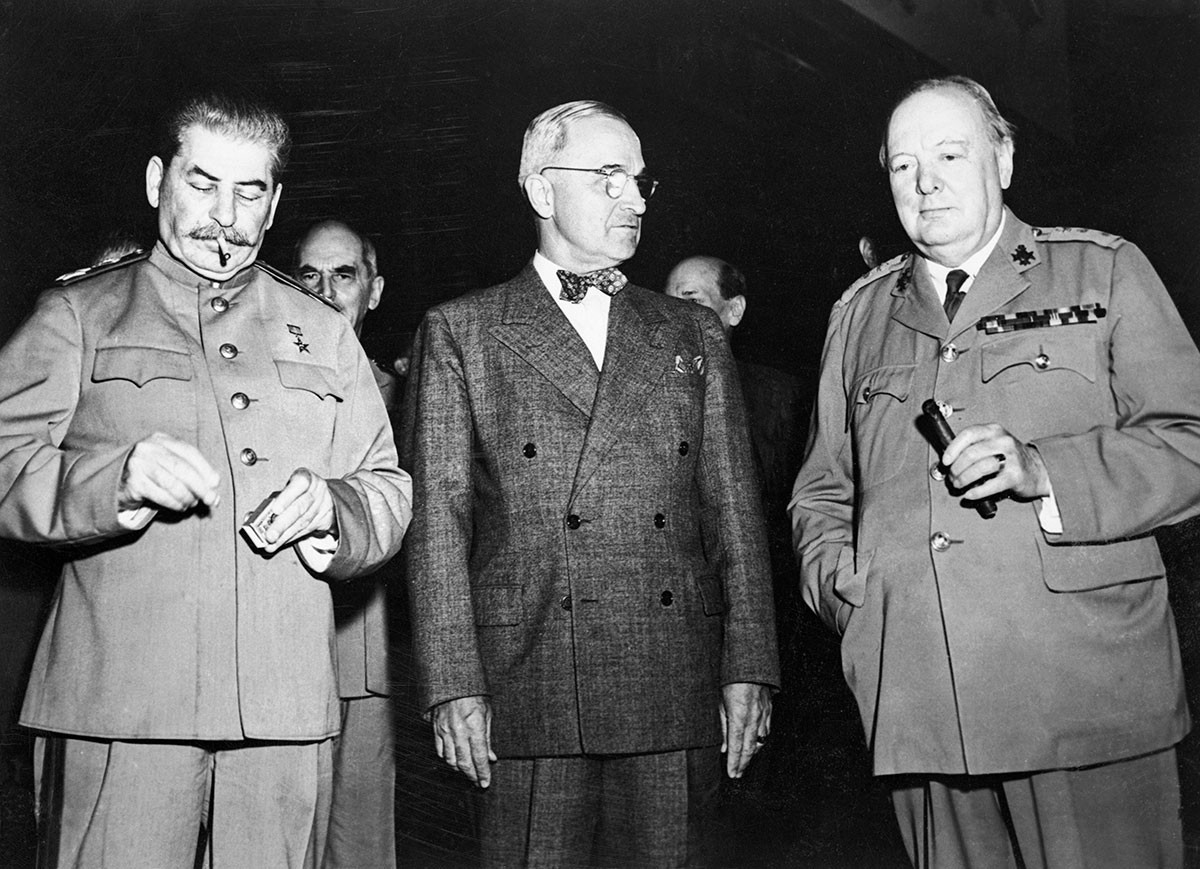

The question of the return of “territories legally belonging to the Soviet Union” and the revision of the status of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles was raised by the USSR in negotiations with the Western powers, too. “The Montreux Convention is directed squarely against Russia... Turkey has been granted the right to close the straits to our shipping, not only in the case of war, but also when Turkey considers there to be a threat of war, which Turkey itself defines...,” Stalin stated at the Potsdam Conference in July 1945: “It turns out that a small state supported by Britain can hold a large state by the throat and not let it pass... The issue concerns the free passage of our ships through the Black Sea and back. But since Turkey is weak [...] we must have some kind of guarantee that this freedom of passage will be ensured.”

Whilst verbally agreeing on the need to review the agreement on the straits, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Harry Truman diplomatically rejected all of the USSR’s demands for bases and claims to Turkish territories. Nor, as it turned out, was the Montreux Convention revised.

Joseph Stalin, Harry Truman, and Winston Churchill in Potsdam.

Getty ImagesAfter the defeat of the Japanese and the end of WWII, relations between the former allies deteriorated rapidly, with the Turkish question acting as one of the catalysts of the incipient Cold War. Churchill made a point of raising the issue in his famous Iron Curtain speech in Fulton on March 5, 1946, which effectively marked the beginning of the great standoff.

Its diplomatic pressure on Ankara brought no dividends to the Soviet Union. On the contrary, it expedited Turkey’s rapprochement with the U.S. and Britain. As early as 1952, it joined the North Atlantic Alliance.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, “in the name of preserving good neighborly relations and strengthening peace and security,” Moscow finally withdrew its claims on Turkey. Years later, one of the main players in those events, Molotov himself, described it as an “untimely, impracticable undertaking.”

American tanks in Turquey in 1952.

Getty Images“Stalin I consider to be a wonderful politician, but he made mistakes,” noted the former People’s Commissar.

In 1957, the new Soviet head of state, Nikita Khrushchev, gave an emotional assessment of the Stalinist policy: “We had defeated the Germans. It was head-spinning. Turks, comrades, friends. Let’s write a note, and they’ll immediately hand over the Dardanelles. No one is that foolish. The Dardanelles are not Turkey, it’s a nexus of states. We terminated the friendship treaty and spat in their faces... It was stupid. We ended up losing friendly Turkey and now have U.S. bases in the south, with our southern flank in the crosshairs...”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox