Alexey Bogolyubov. Battle of Kronstadt.

Public DomainFor almost the entire 17th century, Sweden basked in the glory of great power status. Its army and navy, considered among the strongest in Europe, won a string of brilliant victories in numerous wars, and with them vast new possessions along the shores of the Baltic Sea, effectively turning it into a Swedish lake.

Nils Forsberg. Gustaf II Adolf before Battle of Lützen.

Gothenburg Museum of Art (CC BY 3.0)This state of affairs was radically altered during the course of the Great Northern War of 1700-1721, in which the Swedes locked horns with a coalition of Russia, Denmark, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Saxony. Despite some early successes, defeat in the Battle of Poltava on July 8, 1709, was followed by further failures on land and at sea. At last, in 1721, Sweden was forced to sign the Treaty of Nystadt, under which it ceded to Russia the territories of Livonia (central and northern Latvia), Estland (Estonia), Ingria (today’s Leningrad Oblast and the city of St. Petersburg) and south-eastern Finland.

Alexander Kotzebue. The Victory at Poltava.

HermitageIn Stockholm, however, the defeat was seen only as a temporary setback. The Swedes were confident they would soon regroup and exact revenge. It was a question of when, not if. In 1734, at a meeting of the Secret Committee of the Riksdag (the national legislature), which handled foreign policy and defense, it was decided to do everything necessary “to return Russia to her erstwhile borders.” Active preparations for military action began four years later when hawks hungry for war with Russia came to power – the so-called “Hats” faction, known because members wore the distinctive tricorne hat. (Their dovish opponents they contemptuously referred to as “Caps” – short for nightcaps.)

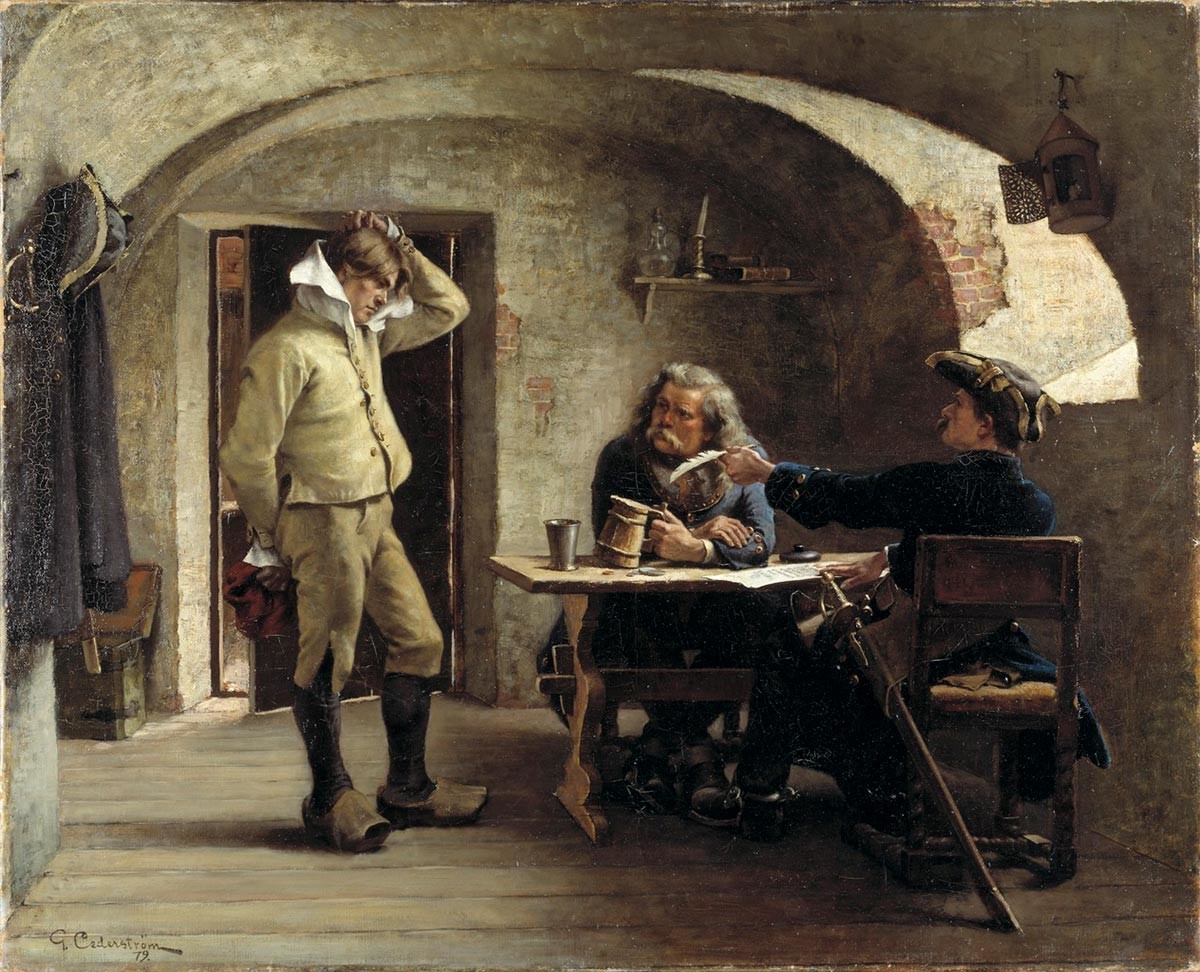

Gustaf Cederström. Recruiting Sergeants.

NationalmuseumOn August 8, 1741, the Kingdom of Sweden declared war on Russia, the official reason being the assassination two years earlier by Russian officers of Swedish diplomatic courier Malcolm Sinclair, who was actively working to bring about a Swedish-Turkish military alliance. Having learned from Sinclair’s documents about Swedish war plans, Russian Empress Anna Ioannovna imposed a ban on bread exports to the country’s northern neighbor, which became a second casus belli. The goal of the campaign was to reclaim all of Sweden’s lost territory, or, at the very least, if things do not go according to plan, Ingria.

Johan Henrik Scheffel. Portrait of Malcolm Sinclair.

EuropeanaStockholm believed that a war with Russia would be quick and victorious. By now, the young Ivan VI had ascended the Russian throne, and a power struggle had broken out between rival court factions. But the Swedish threat was neutralized by the brilliance of the Irish-born Russian commander Peter von Lacy. In August 1741, he routed the enemy at the Battle of Villmanstrand, and exactly one year later his troops surrounded and forced the surrender of the main forces of the Swedish army at Helsingfors (Helsinki). “Henceforth, almost the entire territory of Finland came under Russian control. The defeat of Sweden was practically a foregone conclusion,” wrote Baron Ivan Cherkasov to Vice-Chancellor Alexey Bestuzhev-Ryumin. Swedish commanders Henrik Magnuss von Buddenbrock and Karl Emil Loewenhaupt were found responsible for the failure, recalled and executed.

Portrait of Peter von Lacy.

Public DomainAccording to the terms of the Treaty of Åbo, concluded on Feb. 3, 1743, Russia returned the captured territory of Finland to the Swedes, save for a small piece of land with the fortress of Neishlot (Savolinna). This made it possible to push the border even further away from St. Petersburg. In addition, Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, who had replaced Ivan VI on the throne following a palace coup, demanded that Prince-Bishop Adolf Frederick of Lübeck be recognized as the heir to the Swedish throne. He was the uncle of Prince Karl Peter Ulrich (the future Peter III of Russia), whom the Russian empress, as his aunt, chose as her successor. Elizabeth’s protégé did indeed become king of Sweden in 1751, but that did not bring any dividends to Russia.

Gustaf Lundberg. Portrait of Adolf Frederick, King of Sweden.

HermitageA new attempt to restore Sweden to great power status and throw Russia back from the Baltic coast was made in 1788 by Gustav III. This time the Swedish approach was more careful and cunning – they commenced hostilities right in the middle of the Russian-Turkish war of 1787-1791, when the bulk of the Russian army and navy was tied up in the south. As a pretext for declaring war, a group of Swedish soldiers, dressed in Russian uniform, staged a false-flag attack on the Swedish border crossing at Puumala.

Pehr Hilleström. King Gustav III of Sweden and a Soldier. Episode from the Russian War 1789.

NationalmuseumThe Swedish army won a number of victories in Finland, but advanced into Russian territory with caution. The plan centered on achieving victory at sea and on landing troops close to St. Petersburg. Military action in the Baltic region proceeded with varying success until the Battle of Vyborg on July 3, 1790, when the Swedish fleet was blocked in Vyborg Bay. Losing almost 20 ships and approximately 5,000 men, the Swedes managed to break out, but had to abandon plans to take the Russian capital.

Ivan Aivazovsky. Sea battle near Vyborg.

Public DomainRussia was on the verge of victory when the Swedish fleet accomplished the incredible, smashing the enemy on July 10, 1790, in the Svensksund Strait. More than 500 ships on both sides took part in the largest naval battle ever seen in the Baltic Sea. The Russian fleet lost 35 ships and 7,000 killed and wounded. Another 22 ships were captured by the Swedes, whose own losses were limited to just five small vessels.

Johan Diedrich Schoultz. Battle of Svensksund.

Maritime Museum“The destruction of the enemy was terrible, and the last moments of the battle were gruesome and horrible,” the commander of the Swedish fleet, Gustav III, wrote to his wife Sofia Magdalena of Denmark: “Night fell, there was burning and screaming all around... I hope that if we continue to act thus, then we shall kindly compel the haughty Katarina [Empress Catherine II] to forgive us for our mistakes and sue for peace.” When the dust settled, neither side had achieved a decisive advantage, and the Treaty of Värälä was concluded on Aug. 14 of that same year on status quo terms.

Alexander Roslin. Portrait of Gustav III of Sweden.

NationalmuseumHaving failed in its endeavor, Sweden gave up trying to force a renegotiation of the Treaty of Nystadt. Less than 20 years later, the country itself had to go on the defensive. In 1808, with the support of Napoleon Bonaparte, Russia launched a war against its northern neighbor, culminating in “the greatest national catastrophe in the long history of the Swedish state” — the loss of all of Finland.

Helene Schjerfbeck. Wounded Warrior in the Snow.

Finnish National GalleryIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox