This Moroccan-born Spanish woman was one of the USSR’s most effective spies. Wholeheartedly devoted to the cause, she spent more than 45 years on a risky job spying for the USSR around the world. Yet, throughout the course of her clandestine career, her unquestionable allegiance to Soviet intelligence demanded unparalleled personal sacrifices.

For Soviet intelligence, África de las Heras was a boon. By the age of 28, the Moroccan-born Spanish woman was up to her elbows in political and military struggle in Spain, organizing an armed riot, hiding from state authorities and fighting with the Republican faction in the Spanish civil war. Most importantly for the Soviets, she was a self-proclaimed communist.

In 1937, África was recruited to the Soviet intelligence by Aleksandr Orlov, a Soviet secret agent based in Spain whose defection to the U.S. a year later would endanger the newly recruited undercover agent. Yet, in 1937, África de las Heras received her codename ‘Patria’ and received her first order from Moscow: to smuggle a large sum of money from Paris to Berlin.

África de las Heras.

Press Office of the Russian Foreign Intelligence ServiceTraveling under the guise of a Canadian citizen, África failed to cross the border by train, as her forged passport contained a mistake. Although she was not detained, the newly recruited spy faced a tough choice: either to abort the risky mission or to stake it all on delivering the cash. She chose the latter and successfully completed the mission. Her career as a Soviet intelligence officer had begun.

After Alexandr Orlov had fled his post, África’s mentors feared her identity and the true nature of her work would be revealed and called the agent off to the Soviet Union, her new homeland where she had never been before.

Rafael Videla, head of the Socialist United Party of Catalonia, José Gros and África de las Heras, Soviet partisans during the World War II, 1944.

Press Office of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service“She did not want to live in expensive hotels. ‘We came to fight, not to travel to sanatoriums,’ she used to repeat. But the intelligence [service] had not forgotten her [and provided with] studies, courses. She quickly and somehow very naturally mastered radio engineering and everything else,” said one of África de las Heras’s fellow students, who gave an anonymous interview to a Russian newspaper.

When World War II broke out, África saw it as an opportunity to go to the front line.

“With great difficulty, I was able to restrain my desire to jump for joy and shout at the top of my voice, ‘Hurrah! I’m going to the front! I am the happiest person in the world!’” África de las Heras was quoted as saying at the time.

On the Eastern Front, África, now a naturalized Soviet citizen, provided radio communication to the partisan detachment she was assigned to with a remarkable degree of devotion.

“I solemnly swore that I would not surrender to the enemy alive and, before I died, I would blow up the transmitter, the quartz, the ciphers with grenades,” she was quoted as saying.

A woman of subtle complexion, she had to endure the same hardships that all of the male members of the detachment faced. Stern África stoically endured the permanent stress and all the physical hardships of the front line but one: African-born, she often found the notorious Russian frost unbearable.

“One day [the commander of the partisan detachment] saw the little Spanish girl, all shivering, warming her hands over the fire and her stiff, crooked fingers wouldn’t warm up. And then, Kuznetsov [the commander] instantly took off his sweater, gave it to [África] and she, tiny as she was, went from head to toe into his warmth,” recalled África’s student.

Soviet intelligence officer Nikolai Kuznetsov, the commander of the partisan detachment, in the uniform of a German officer.

TASSAlthough the cause she was fighting for prevailed in the war, África lost her fiancé, a Byelorussian officer killed in action. Mourning, she did not know yet that her supervisors in the Soviet intelligence would arrange her personal life as they deemed beneficial for their business.

Immediately after the war, however, África was made an undercover Soviet spy. As the Cold War was gaining momentum, the Soviet Union worked on extending its spy rings in various countries in the west. África de las Heras was to become one of the USSR’s chief assets abroad.

The service to her new motherland demanded an unprecedented personal sacrifice from África: she had to cut all ties between her and her friends and family members, including her sister, who resided in Europe.

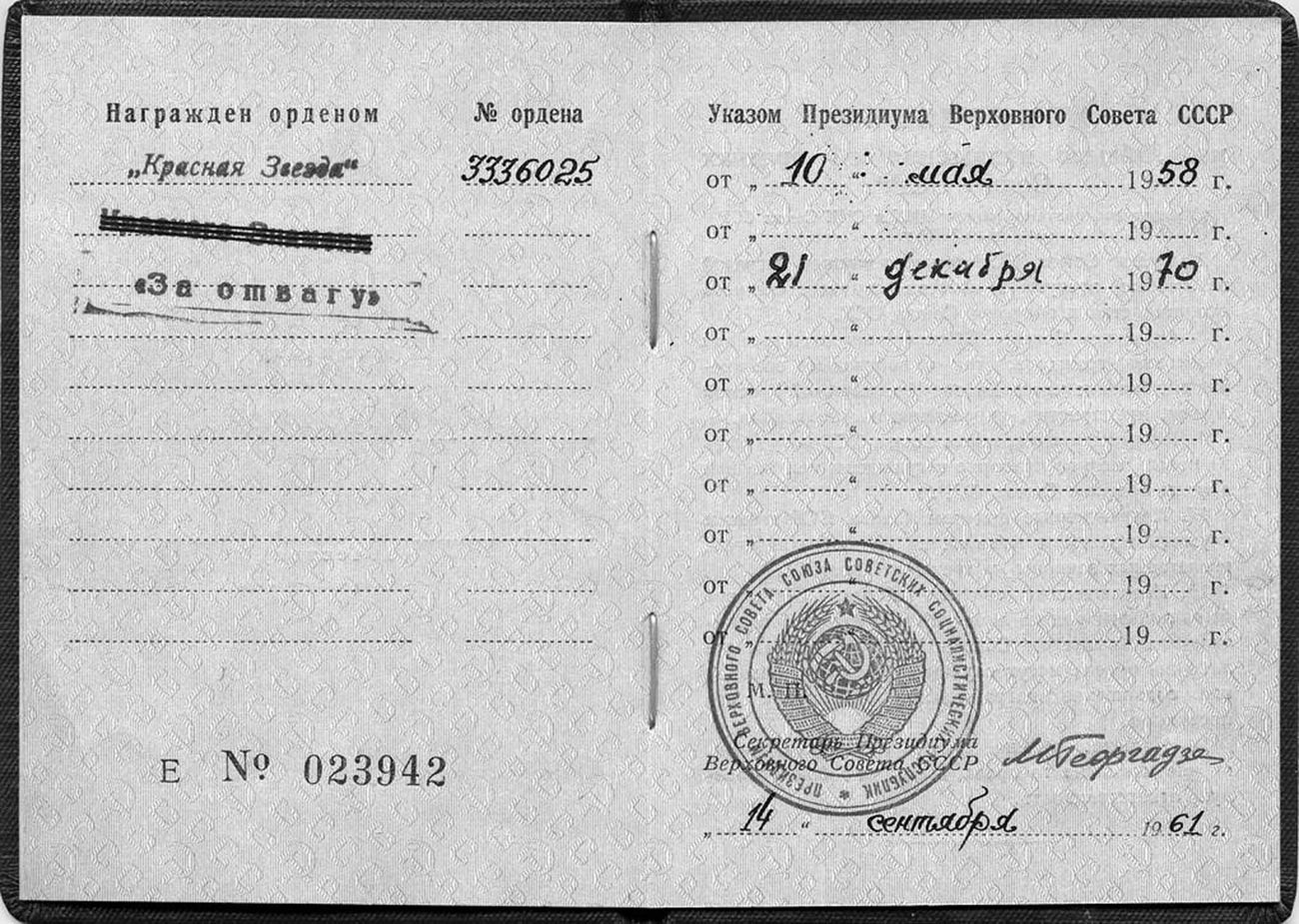

A record in Africa's Soviet Order Book.

Press Office of the Russian Foreign Intelligence ServiceAs an intelligence officer, she worked in Berlin, Paris and then, in 1948, she was stationed in South America, where she formed and managed a network of informants under the cover of an antique store in Montevideo, Uruguay, for 20 years.

To strengthen her cover and enhance her espionage efforts, Moscow judged its female agent might require help in the form of a husband. In 1956, she was informed she would be joined by a comrade who would play the role of her husband. Giovanni Antonio Bertoni, an Italian-born Soviet intelligence officer, soon arrived and, gradually, the couple developed a personal relationship in addition to professional.

Giovanni Antonio Bertoni, an Italian-born Soviet intelligence officer.

Press Office of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service“Without hesitation, she accepted the proposal from her superiors and entered into a marriage with a stranger. Although África and Bertoni formed the couple at Moscow’s behest in order to facilitate the important intelligence missions assigned to them, their marriage turned out to be a happy one,” wrote historian Vladimir Antonov in his book about Soviet intelligence.

África de las Heras.

Press Office of the Russian Foreign Intelligence ServiceWhen her partner and husband died in 1964, widowed África stayed to work in South America for three more years before she left for Moscow, where she taught spycraft to the next generation of Soviet intelligence officers.

“My homeland is the Soviet Union. It is ingrained in my mind, in my heart. My whole life is connected with the Soviet Union... Neither the years nor the difficulties of the struggle have shaken my faith. On the contrary, difficulties have always been a stimulus, a source of energy for my further struggle. They give me the right to live with my head held high and my soul relaxed and no one and nothing can take this faith away from me, not even death,” she is said to have written in the later years of her life.

The legendary and decorated Soviet spy died on March 8, 1988. Colonel África de las Heras is buried in Khovanskoye Cemetery in Moscow.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox