Early in the morning on November 5, 1952, the residents of Severo-Kurilsk were woken up by strong underground tremors. It was two minutes to four in the morning.

The walls of houses cracked and swayed, plaster came down, ceiling lights rattled and crockery, books and photographs fell to the floor. In their fright, people jumped out of their beds and rushed outside without getting dressed. A volcanic eruption? It was only to be expected: on Paramushir Island in the Pacific Ocean where Severo-Kurilsk is situated, there are 23 volcanoes, five of which are regarded as active. The nearest one, Ebeko, was just seven kilometers away and gave regular reminders of itself by spewing out volcanic gases.

But, that morning, the volcanoes remained dormant and had nothing to do with what was happening. The town had 40 minutes left to live.

The strong tremors were caused by a powerful earthquake in the Pacific Ocean measuring 8.3 on the Richter scale. The epicenter was under the ocean floor at a depth of 30 km and 200 km from the coastline. The tremors continued for another half an hour and, during this time, 700 km of coastline were subjected to damage: from the Kronotsky Peninsula to the northern Kuril Islands.

The Kuril Islands of Paramushir

NASAThe damage was notable, but not catastrophic. No-one was hurt as a result of the tremors. Later, in his report about what had happened, the chief of the Severo-Kurilsk police department, P. M. Deryabin, would write: “On the way to the district police department I could see cracks in the ground five to 20 cm wide. Arriving there, I saw that as a result of the earthquake the building was broken into two and the stoves were shattered.”

By that time, the perceptible tremors had already ceased and “the weather was very calm”. But soon, the silence was interrupted by a loud noise and crashing sound coming from the sea, which was 150 meters from the police station. “Looking across, we saw that a high wall of water was advancing towards the island from the sea. <...> I gave the order to open fire with handguns and to shout ‘the water is coming!’ while, at the same time, heading towards the hills,” Deryabin wrote.

At the time, not everyone could make out that it was the water that was coming. Some people thought that the shouting was about “war” not “water” and, when the wave hit the island, they decided that the island had been attacked. People fled. The wave was not that high, just over a meter. The first wave flooded and destroyed the first houses closest to the sea. About 10-15 minutes later, the water started to recede and many people went back to their houses to collect their surviving belongings. It was a fatal mistake.

The ocean retreated, but then hit the town with a second tsunami, producing a devastating 10-meter-high wave. Meeting no particular resistance on its way (the first wave had swept away a considerable part of the obstacles), the water rushed at great speed into the interior of the island.

That morning, in addition to Severo-Kurilsk, a large wave also hit Mussel Bay on Onekotan Island (9.5-10 meters) and Piratkov (10-15 meters) and Olga (10-13 meters) bays on Kamchatka. But, Severo-Kurilsk was its main victim: In a matter of minutes, an entire town with a population of 6,000 was washed away.

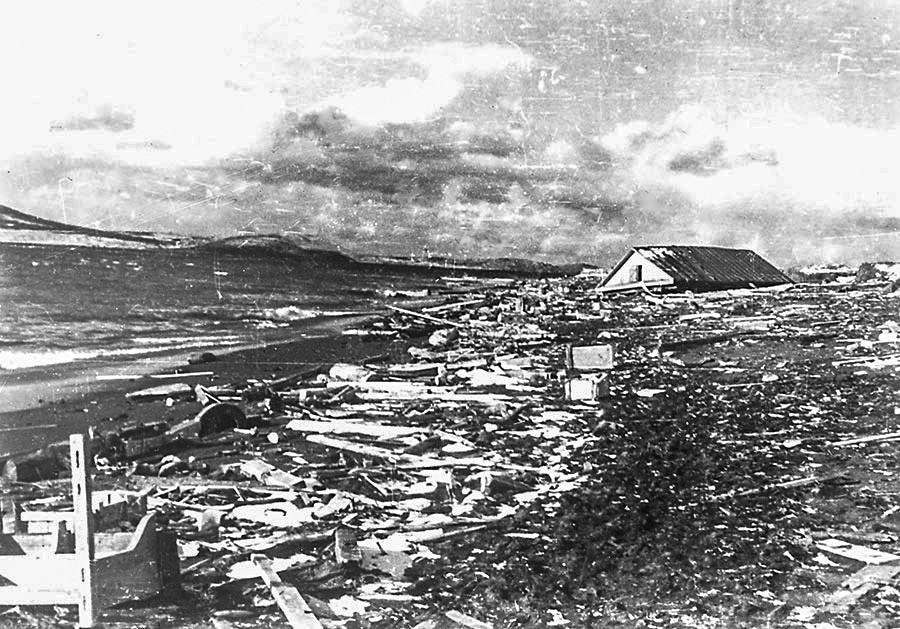

Then a third wave came. Weaker than the second, it finished off the destruction and carried out to sea almost everything that remained on the coast.

“For 20-30 minutes (the duration of the two enormously powerful, almost simultaneous waves) there was a terrible noise in the town caused by the rushing water and crumbling buildings. Houses and the roofs of buildings were thrown around like matchboxes and carried out to sea,” the police chief recalled.

Afterwards, B. E. Piip, head of the Kamchatka volcanological station of the USSR Academy of Sciences, would write in his diary: “A small part of the town located on the terrace sections, as well as the power station and radio communication station, survived. The radio station was constantly sending out an SOS but in a somewhat incoherent manner, so that Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky couldn’t understand anything.” A tsunami warning service didn't yet exist in the USSR at the time.

After the disaster, Piip sailed by boat along the coastline to record the height of the tsunami for a special commission of inquiry. He was told tragic stories in different places. “For example, two sailors in their underwear and vests remained in the water from 5 am to 5 pm, holding on to the wreckage of a house. When they were rescued, one of them collapsed and died upon getting ashore, while the other one survived. <...> For a long time the sea yielded up the corpses of the dead, littering the seashore with them.”

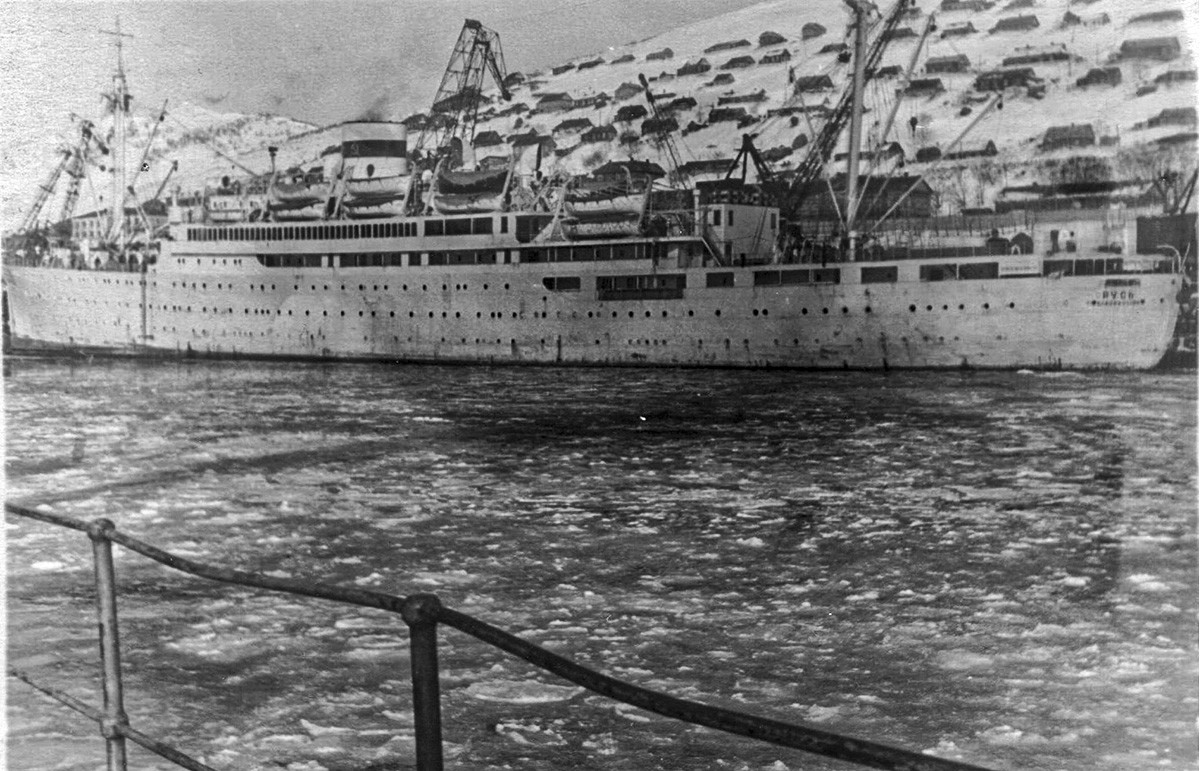

An aircraft that arrived at Paramushir in the early morning discovered that Severo-Kurilsk had been swept away. The whole gulf was full of fragments of houses, beams and barrels, to which the survivors clung. An air and sea evacuation was immediately declared. It was the evacuation of border guards and army units that had been present in the town that, according to researchers, caused the Severo-Kurilsk disaster to be immediately hushed up.

Pravda, the newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, printed not a word about the disaster in the Far East either the next day or in the days that followed. Izvestiya was also silent. Aware that its readers would have seen the aftermath of the devastation with their own eyes, the regional newspaper, Kamchatskaya Pravda, failed to go to press on November 8, 9 and 10. On November 11, it reported the news, but a completely different piece of news: “With enormous elation and enthusiasm the Soviet people have celebrated the 35th anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution.”

The facts about the disaster were only partially declassified in the early 2000s, when access was allowed to official navy records (the Ministry of Defense records are still under wraps). According to these archives, a total of 2,336 people were killed in the disaster in the Northern Kurils. At the same time, historians believe that the tsunami of November 5, 1952 claimed at least 8,000 lives and that almost 2,000 of these were children and teenagers, while only civilians and only those whose bodies were found and identified were included in the statistics.

The disaster had one important consequence: In 1956, the USSR set up a seismic and meteorological service whose duties included the detection of earthquakes at sea and early warning of tsunamis.

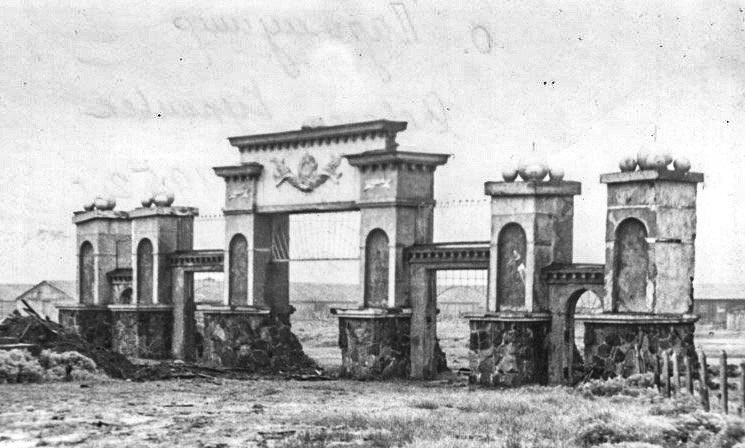

New Severo-Kurilsk, in a high place. 1954

Family archive of G.I.DavydkinAs for Severo-Kurilsk itself, the town lived through difficult times after the tsunami. Many people who were evacuated decided never to return, because the fishery processing plants and depots, which were the main local employers, were badly damaged and had to close. The military contingent was also significantly reduced. The situation only got worse when, in 1961, the migration of herring ceased in coastal waters, dealing another blow to Severo-Kurilsk’s principal industry.

The town was rebuilt in the wake of the tsunami, but it was moved closer to the volcanic hills - to the ancient marine terrace located more than 20 meters above sea level. Even this location is not ideal - now Severo-Kurilsk is in the path of mudflows from eruptions of the Ebeko volcano. The town has 2,691 inhabitants today and it is the only populated area on the entire island.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox