Napoleon’s defeat in 1812 was devastating. In ‘Political and Military Life of Napoleon’, Antoine-Henri Jomini wrote that Napoleon deployed more than 300,000 troops in direct invasion of Russia (while the total number of the Great Army was more than 600,000 at the time).

During the Battle of Berezina (26-29 November 1812), the last scraps of the Great Army tried to flee Russia and there were just 20-30 thousand remaining. About 90% of Napoleon’s army were killed or wounded during the Russian campaign.

However, in the European newspapers, this defeat was attributed mainly not to the military prowess of Russians, but to the harsh cold the French army experienced.

"On the main road. Retreat" by Vasiliy Vereschagin

Vasiliy Vereschagin / Museum of the 1812 Patriotic War / Public domainNewspaper ‘Le Monitor universel’ was Napoleon’s main weapon of propaganda. During the 1812 campaign, ‘Le Monitor’ published bulletins that informed the French about the war, often authored by Bonaparte himself. The Emperor understood that the soldiers of his army would, too, read the bulletins and he felt the need to encourage them during the campaign. The bulletins, Russian scholar Anastasia Nikiforova writes, emphasized the feats of Napoleon’s soldiers and kept silent about the victories of the Russian army.

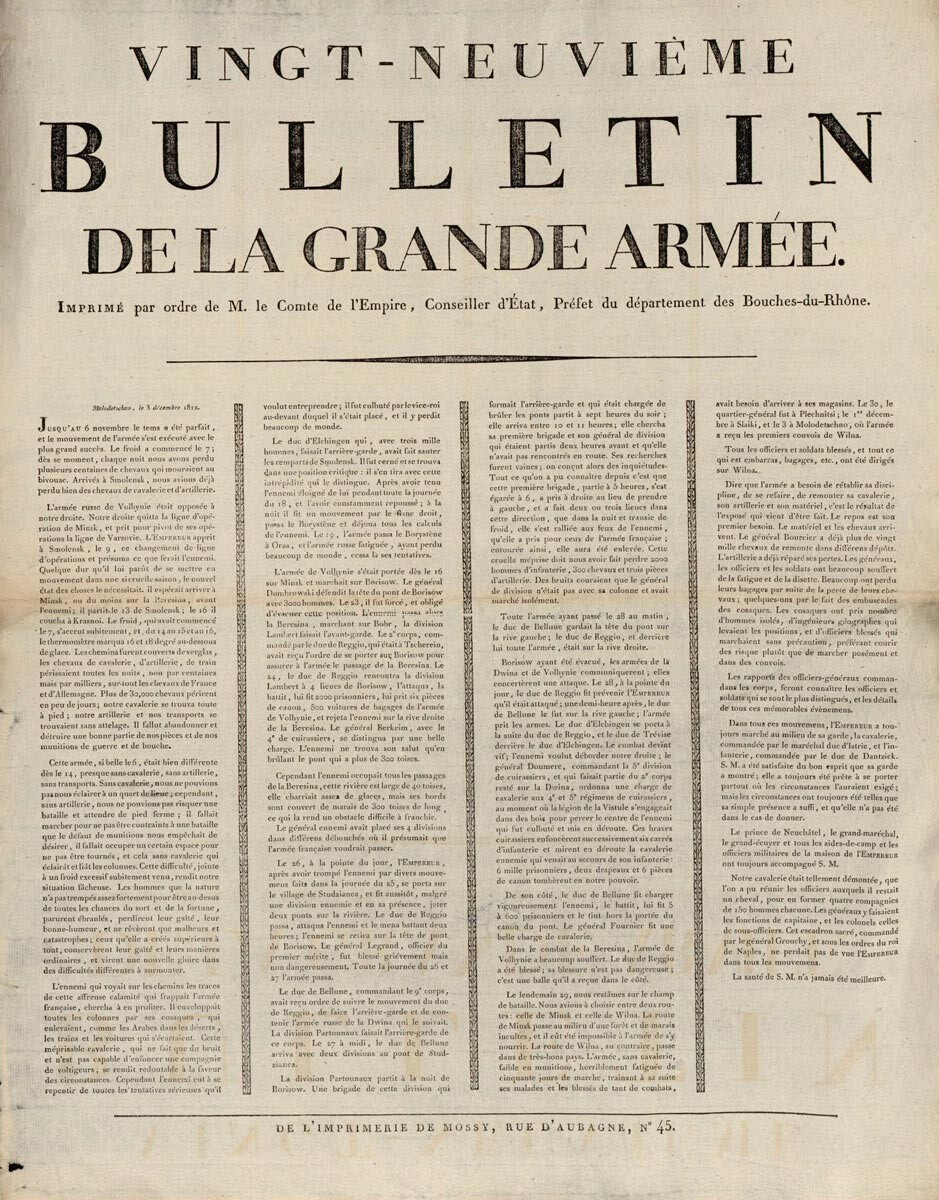

The bulletins regularly informed their readers about the weather. On October 26, the 24th bulletin wrote: “The weather is very good. The first snow fell yesterday. In twenty days, it is necessary to be in our winter quarters.” However, the final, 29th bulletin, that concluded the defeat of the Great Army, complained about the weather as the worst nightmare of the campaign!

A page from the 29th Bulletin of the Great Army.

Public Domain“On November 14, 15 and 16, the thermometer was sixteen and eighteen degrees below zero. The roads were covered with ice; cavalry, artillery and baggage horses were killed every night, not by hundreds, but by thousands, especially German and French. Our cavalry was left without horses, artillery and baggage, without means of transportation. We were forced to abandon and destroy most of our guns, ammunition and food. The army, which was still in order on the 6th, on the 14th looked completely different; it almost completely lost its cavalry, artillery and vehicles,” the bulletin concluded.

It all looked like it was only the frost, and not the Russian army, that deprived the French of their cavalry, artillery and had inflicted an utter defeat on them! Didn’t the French soldiers see winter before? Of course they did.

In 1795, the French army warred the Netherlands during a harsh winter. When Russian and French armies clashed at the Battle of Eylau (February 7-8, 1807), temperatures were freezing, still, the French maneuvered on the frozen lakes and rivers during a blizzard. So winter couldn’t be new for them.

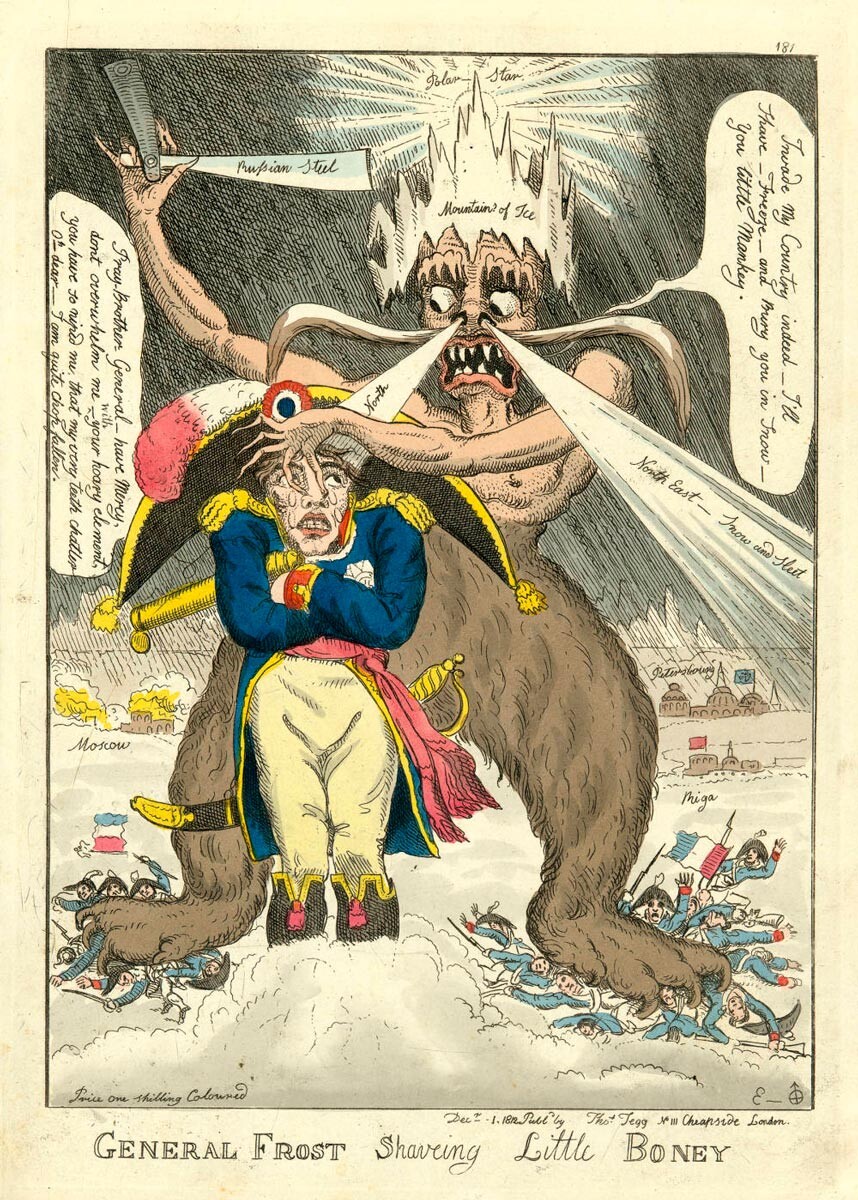

General Frost Shaveing Little Boney, William Elmes, 1812.

University of Washington / Public DomainHowever, the legend of the deadly cold that Napoleon created was readily accepted not only by the French public, but by the British press and public, as well. Great Britain still was one of Russia’s main international rivals and it wasn’t profitable for them to praise the military and strategic skills of Russian generals and officers. It was much more convenient to say that the French army was defeated because of the cold – this way, Russians wouldn’t seem so powerful and menacing. The very words “General Frost” were apparently coined by William Elmes, the creator of a British cartoon ‘General Frost shaveing little Boney’ (see above). But what did Russians themselves have to say about this?

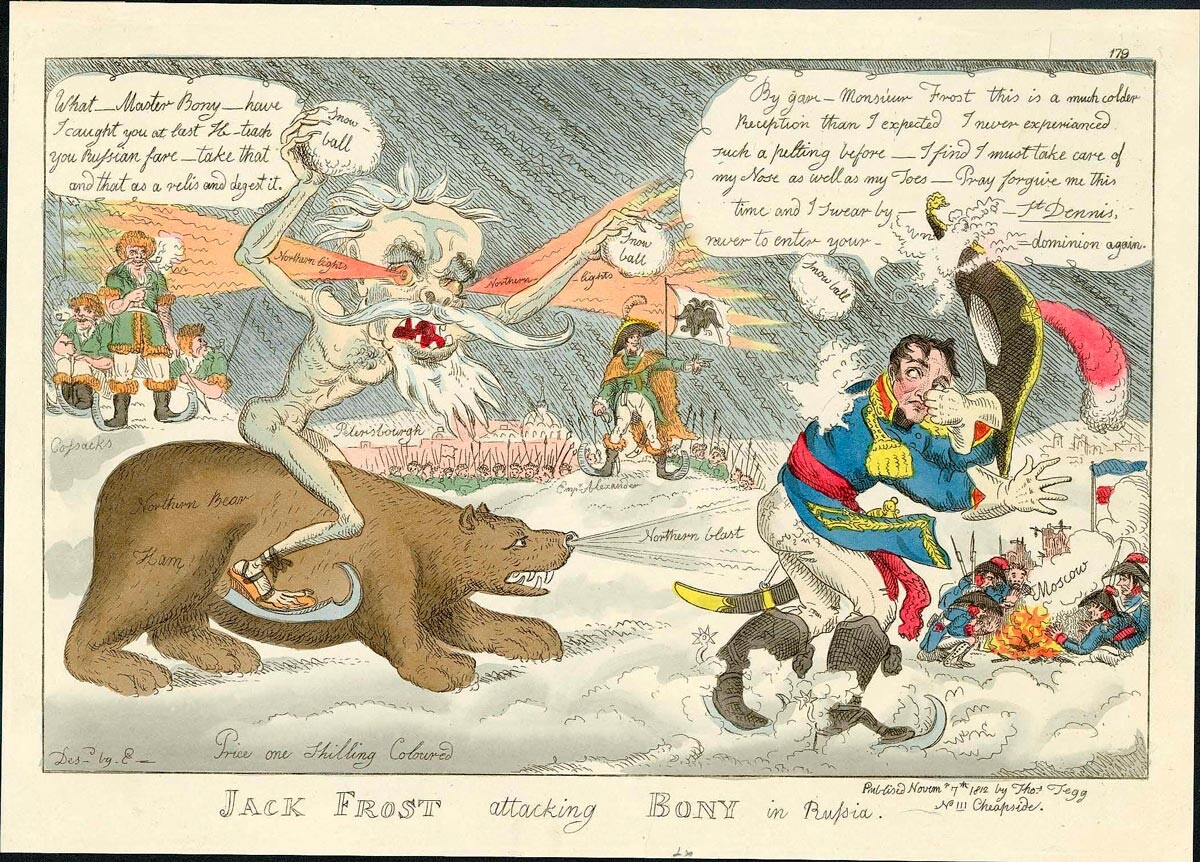

JACK FROST attacking BONY in Russia, William Elmes, 1812

Public DomainDenis Davydov, a general and leading partisan commander in 1812, fiercely opposed the idea that Napoleon’s army died solely from the cold. In his article devoted specially to this topic, Davydov quotes Georges de Chambray, French artillery general who took part in the campaign and was captured by Russians at Berezina:

“The cold, dry and moderate, which accompanied the troops from Moscow to the first snow, was more useful than fatal [for the army]. On October 27, it was 5 below zero. November 9 – 15 below zero, and November 12 and November 13 – 21 below zero,” de Chambray wrote. These last two days were actually the coldest and then the thaw stroke, which actually hindered some of the French troops from advancing Berezina – the river wasn’t frozen and thousands perished in the water.

"Battle of Eylau, 1807," by Jean-Antoine-Siméon Fort, 1807.

Palace of Versailles / Public DomainGeneral Jomini straight off opposes the idea of winter being the main reason for Napoleon’s defeat. “The main reasons for the unsuccessful venture to Russia were attributed to the early and excessive cold; all my adherents repeated these words to satiety. This is completely false. How could they think I didn’t know about the timing of this annual phenomenon in Russia…! Not only did winter come no earlier than usual, but its arrival on November 7 was later than it happens every year,” Jomini wrote. “This cold did not exceed the cold of the Eylau campaign. But, at Eylau, my army was not upset, because it was in a land of abundance and that I could satisfy all its needs. The opposite happened in 1812: the lack of food and everything necessary caused the troops to scatter.”

"Napoleon at the Borodino Heights," by Vasiliy Vereschagin

Vasiliy Vereschagin / State historical museum / Public domainWe already know how Mikhail Kutuzov lured Napoleon into Moscow, trapping him there, and that this strategy of destroying Napoleon’s army by exhaustion was actually devised by Barclay de Tolly. So the main reasons for Napoleon’s defeat were purely military, not related to weather or low temperatures.

Indeed, the Great Army, scattered and disorganized, wasn’t properly supplied. The partisan movement also played one of the main roles in the defeat – everywhere Russian peasants encountered French soldiers, they most likely killed them.

Denis Davydov by George Dawe

State Hermitage / Public domain“Peasants of the nearby village terminated a team of the Teptyar Cossack regiment of the Russian Imperial Army, consisting of sixty Cossacks,” Davydov recalls in his memoirs. “The peasants mistook these Cossacks for the enemy, because of their impure pronunciation of the Russian language.” Teptyars were Bashkir people, and they knew Russian. Just not well enough. The peasants killed them nevertheless, so great was the hatred for the invaders. In such conditions, and also chased and attacked by the Russian army during the retreat, the French army was doomed.

Sir Walter Scott, in his book ‘The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte’, wonders: “If frost and snow in Russia are such insurmountable disasters, powerful enough to destroy entire armies, then how did these circumstances not enter into the calculations of a general so famous [as Napoleon], who conceived an enterprise so huge? Does it never snow in Russia? Is frost in November a rare phenomenon there?”

“Napoleon foresaw,” Scott concludes, “that a cold would come in October. In July, he foresaw the need to collect food supplies sufficient for the food of his army. But, carried away by impatience, in neither case did he take measures to overcome either hunger or cold, which he foresaw.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox