January 1st wasn’t always a holiday in Russia. It became official on December 23, 1947, when the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree "On declaring January 1st a non-working day.” Before that, Russians had to go to work on the first morning of the New Year. However, January 1st wasn’t always the first New Year morning in Russia. In the past, Russians celebrated their New Year in September, and even earlier – in March!

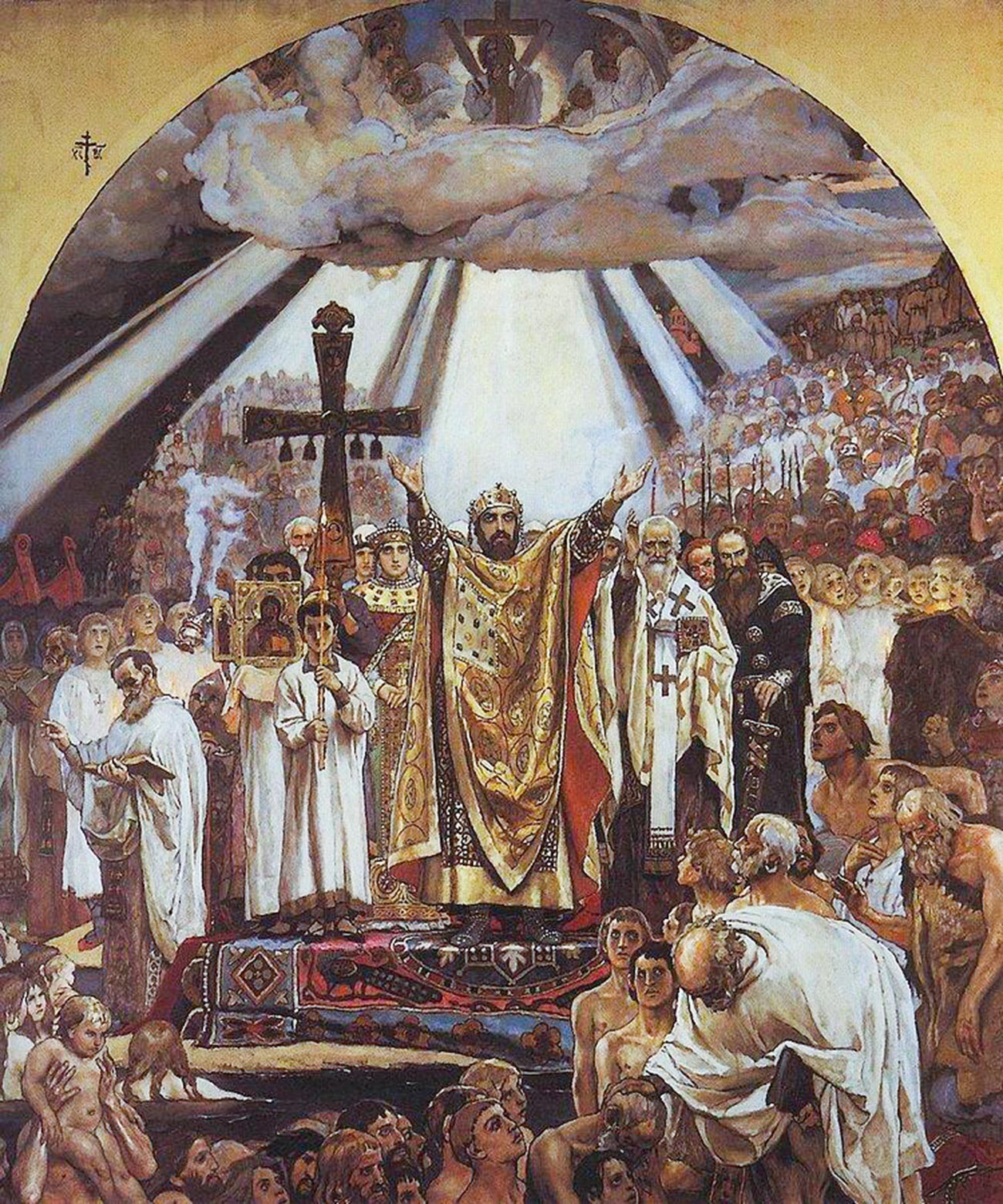

"The Baptism of Rus'" by Viktor Vasnetsov

Viktor VasnetsovIn ancient Russia, the New Year was celebrated on March 1st. Why exactly on this day? Historians are still uncertain. The first hypothesis suggests this was simply because the agricultural year starts in March. Another assumption is that pre-Christian Russians somehow adopted March 1st as the first new year’s day from the first month of the ancient Roman calendar, which had 10 months.

When in 988, Russians were introduced to Christianity, the first day of New Year stayed the same – because Kievan Rus’ started using the Byzantine calendar. The Byzantine Empire, that introduced the Russian lands to Christianity, used a calendar (also called “Creation Era of Constantinople” or “Era of the World”), created in Constantinople (modern Istanbul) in 353.

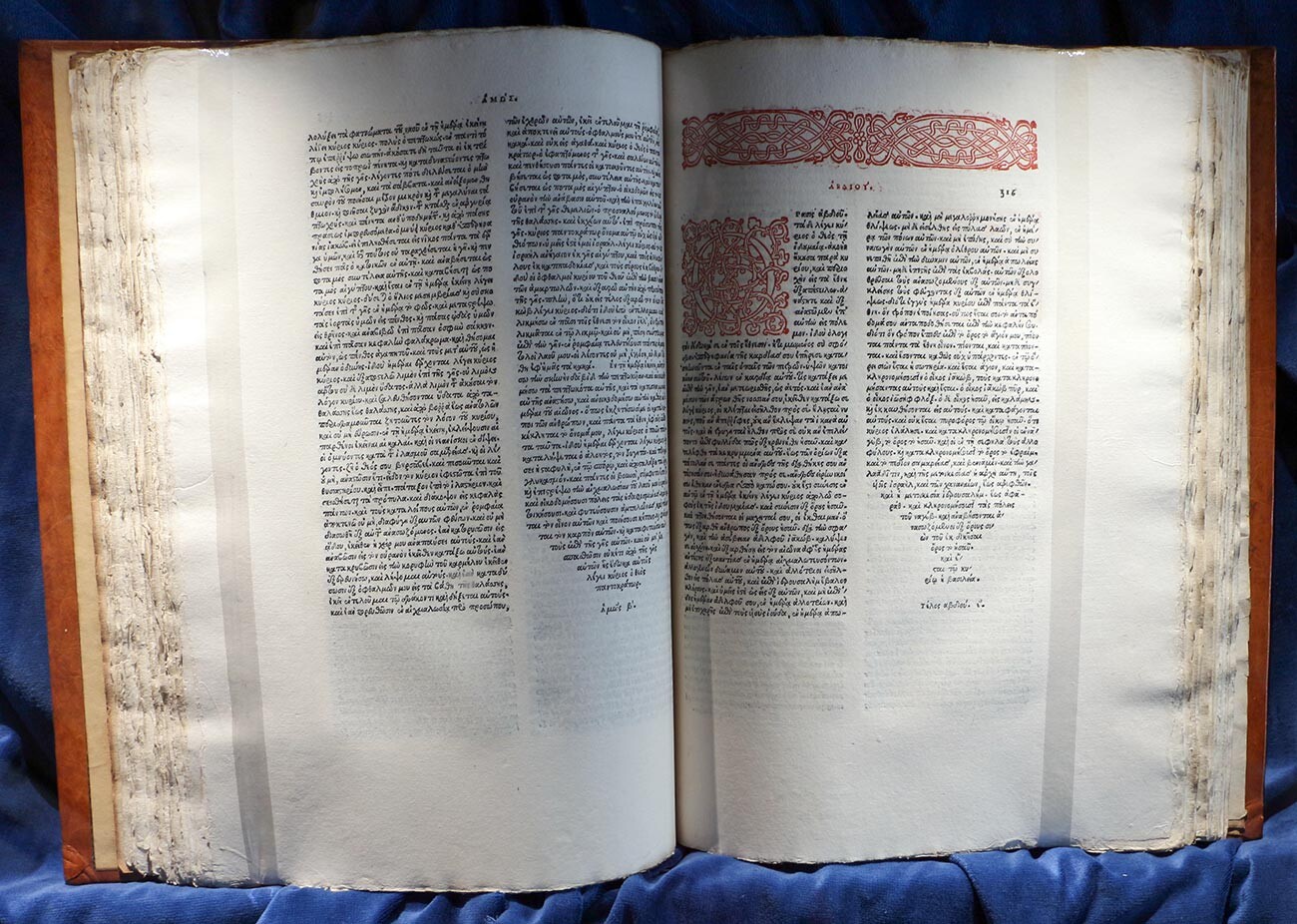

This calendar started from the creation of the world – according to Septuagint (the earliest known Greek translation of the Hebrew bible), it happened around 5508 years before Jesus Christ was born. From approximately the 7th century, the Byzantine New Year started on March 1st – so it was very fitting for Russians. Their first year was 6496 in the Byzantine calendar. However, the same year, the Byzantine Empire moved the beginning of the year to September 1st.

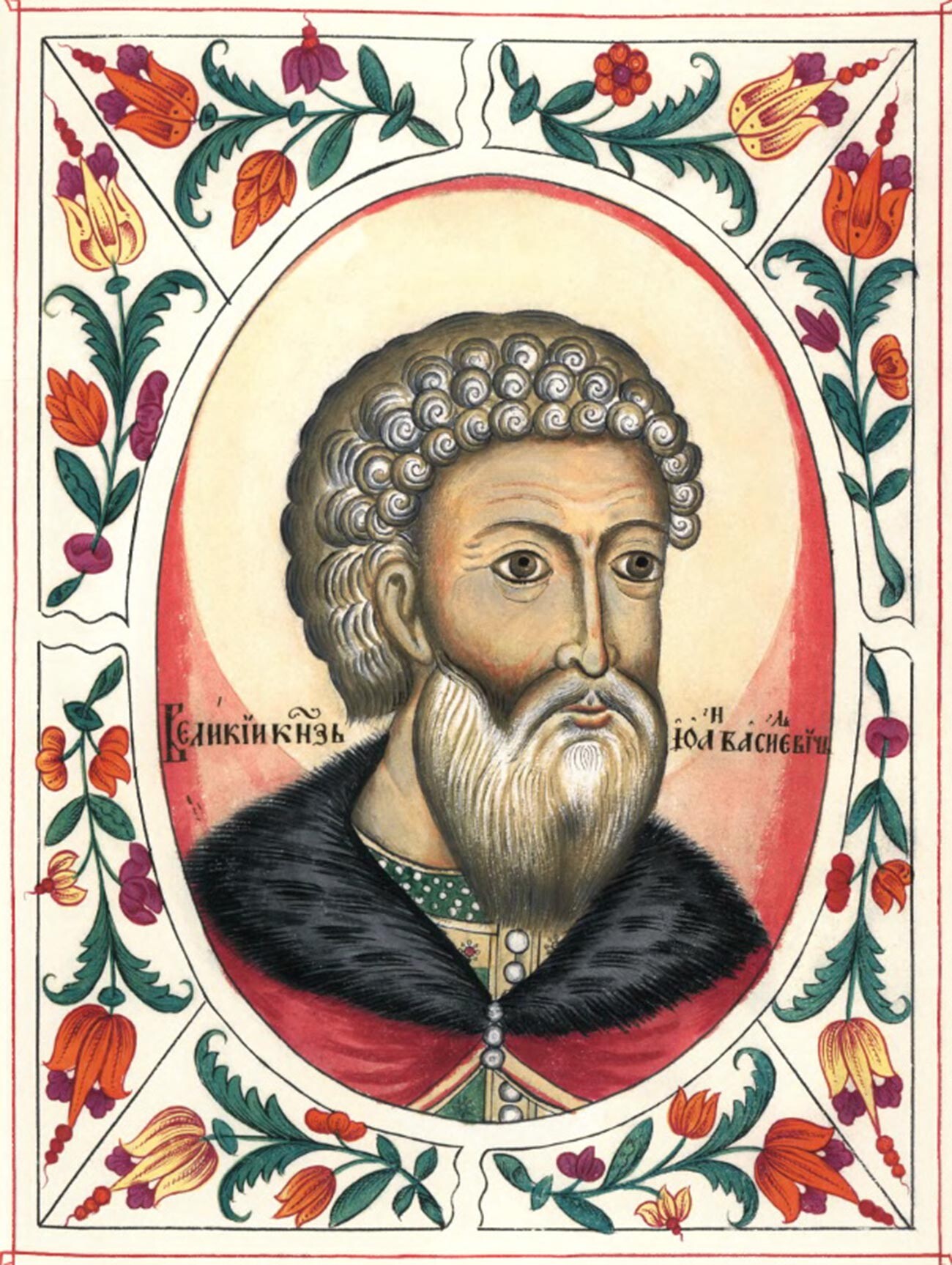

Ivan III of Russia

From the 10th century until 1492 in Russia, both September 1st and March 1st were used as the first days of the New Year. In daily life, New Year was celebrated in March. September was used in dating official documents like agreements, contracts, certificates, but more importantly, the Orthodox Church celebrated the New Year on September 1st – just like the Byzantine Empire.

But 1492, counting from the Creation, would have been the year 7000-7001. According to many prophecies that circulated in the (very superstitious) Russian society of the late 15th century, this was the year when the Antichrist would descend – the end of the days. Most Russians, even the noblest and most educated ones, believed these prophecies.

On September 1st, 1477, Maria Yaroslavna, the mother of Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow, even sent the massive sum 495 rubles (a mature stallion at the time cost 6-10 rubles) to Kirillo-Belozersky monastery as an endowment. “According to the terms of the endowment, the monks had to constantly pray to God for the family of the Moscow princes for 15 years, that is, exactly until September 1, 1492,” historian Nikolay Borisov writes.

Most Russians believed in the End of the Days as well – sources show that in 1492, the number of trading deals was significantly lower than in 1491 or 1493. However, most of Moscow’s Orthodox hierarchy and civil authorities didn’t treat the prophecies seriously. Dmitry Trakhaniot, a Greek diplomat and religious scholar in Ivan III’s service, noted in his letters that neither Jesus himself, the prophets, or the saints spoke about the end of the world after seven thousand years from Creation, and this was nothing more than human speculation. The absolute truth is contained only in the words of Jesus Christ: “But about that day or hour no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father.”

The Aldine Bible, an edition of the Bible in Greek begun by Aldus Manutius, and published in Venice in 1518 by the Aldine Press. It is the first complete Bible printed entirely in Greek (the Old Testament in the Septuagint) to be published.

Sailko (CC BY 3.0)Indeed, nothing “eschatological” happened on September 1st, 1492 (or, year 7001 in the Byzantine calendar system). Instead, the Moscow Council of the Orthodox Church decreed that the New Year should start on that day – in daily life, and the New Year in March must be dropped altogether. This decision had political reasons behind it.

Almost 40 years previously, in 1453, Constantinople was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, and in 1472, Grand Prince Ivan III of Moscow married Sophia Palaiologina, the niece of the last Byzantine Emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos. Marrying her, and 20 years later, installing September 1st as the new New Year, Ivan III sent a plain message to the world: now, after the fall of Byzantium, only the Moscow state could be a truly devout Orthodox state. This political and religious concept, later known as “Moscow, third Rome,” was developed by Ivan III’s successors on the Moscow throne.

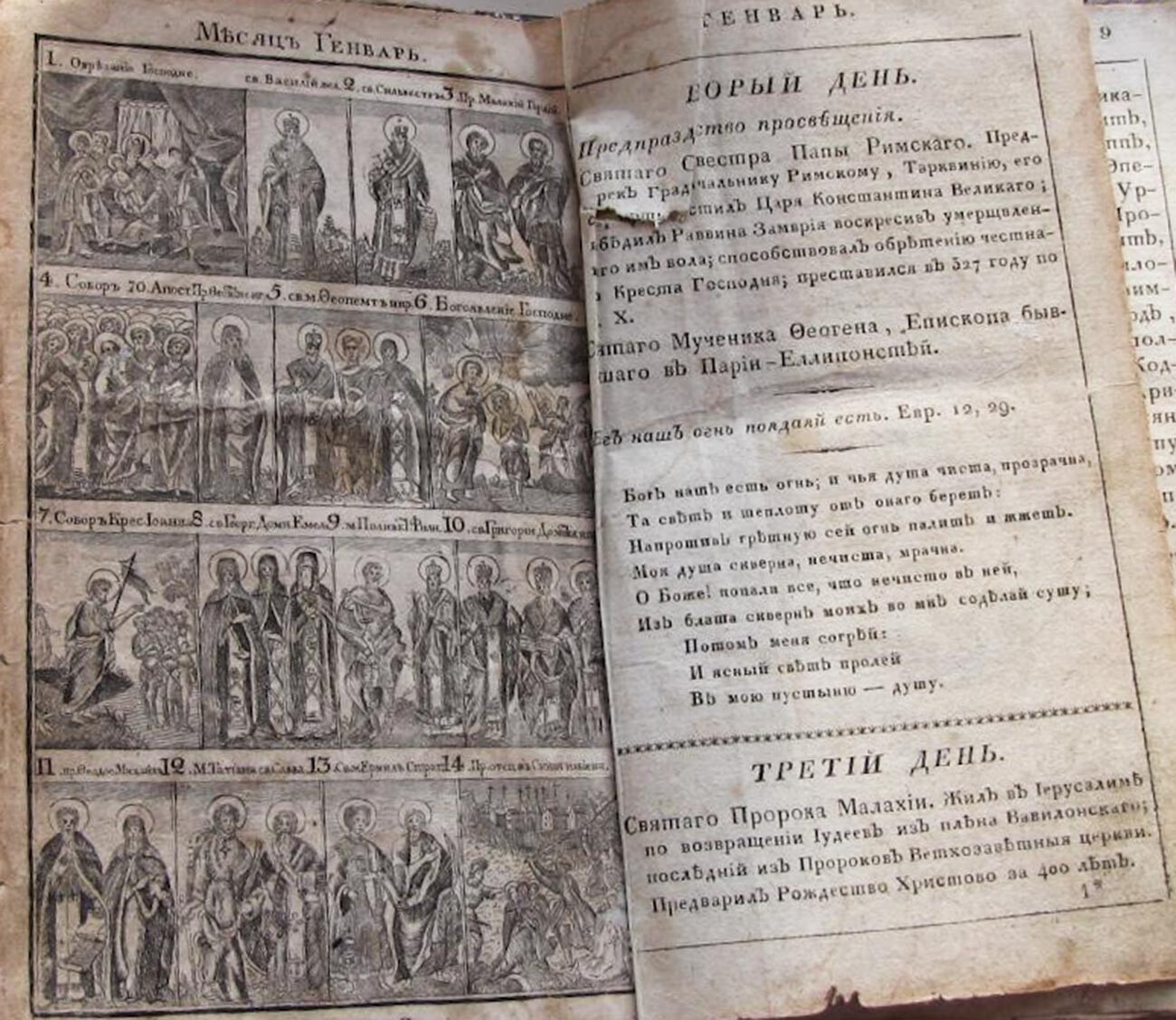

A Russian calendar of the 19th century

For more than 200 years, 1492-1699, Russian people, as well as the Russian Orthodox Church, celebrated New Year on September 1st. It became a solid tradition.

Meanwhile, Europeans lived by completely different calendar systems – first, the Julian calendar (known as “Old Style”), and, starting from 1582, the Gregorian calendar that we still use today (also known as “New Style”). Both these calendars started from the Nativity of Christ, not from the first day of Creation. They were also much easier to calculate and read than the Byzantine calendar, and the year began on January 1st, not in March or September.

Peter the Great considered international trade one of the key factors of Russia’s development. He understood that in order to successfully trade with Europe, Russians must not only look more like Europeans, and know foreign languages – they must have the same New Year as the Europeans.

Different New Years created a problem: in Europe, early September was a typical working month when deals were made and contracts signed – meanwhile, in Russia, people celebrated New Year and had a week or more off. For Peter the Great, it meant only one thing – money being lost.

On December 19, 7208 (Byzantine style), Peter issued a decree: the day of December 31, 7208, would be followed by January 1, 1700. The year 7208, thus, turned out to be the shortest for Russia, since it lasted only four months – from September to December.

In the same decree, Peter also issued recommendations on how the New Year should be celebrated “the European way.” After prayer, the tsar wrote, one needs to decorate one’s house and gates with pine, spruce or juniper branches and congratulate each other on the beginning of the New Year and the new century.

Nobles were ordered to arrange festive shooting from small calibre cannons, muskets and pistols. Peter also recommended that from January 1 to January 7, people were free to use fireworks, and light festive lights in their yards.

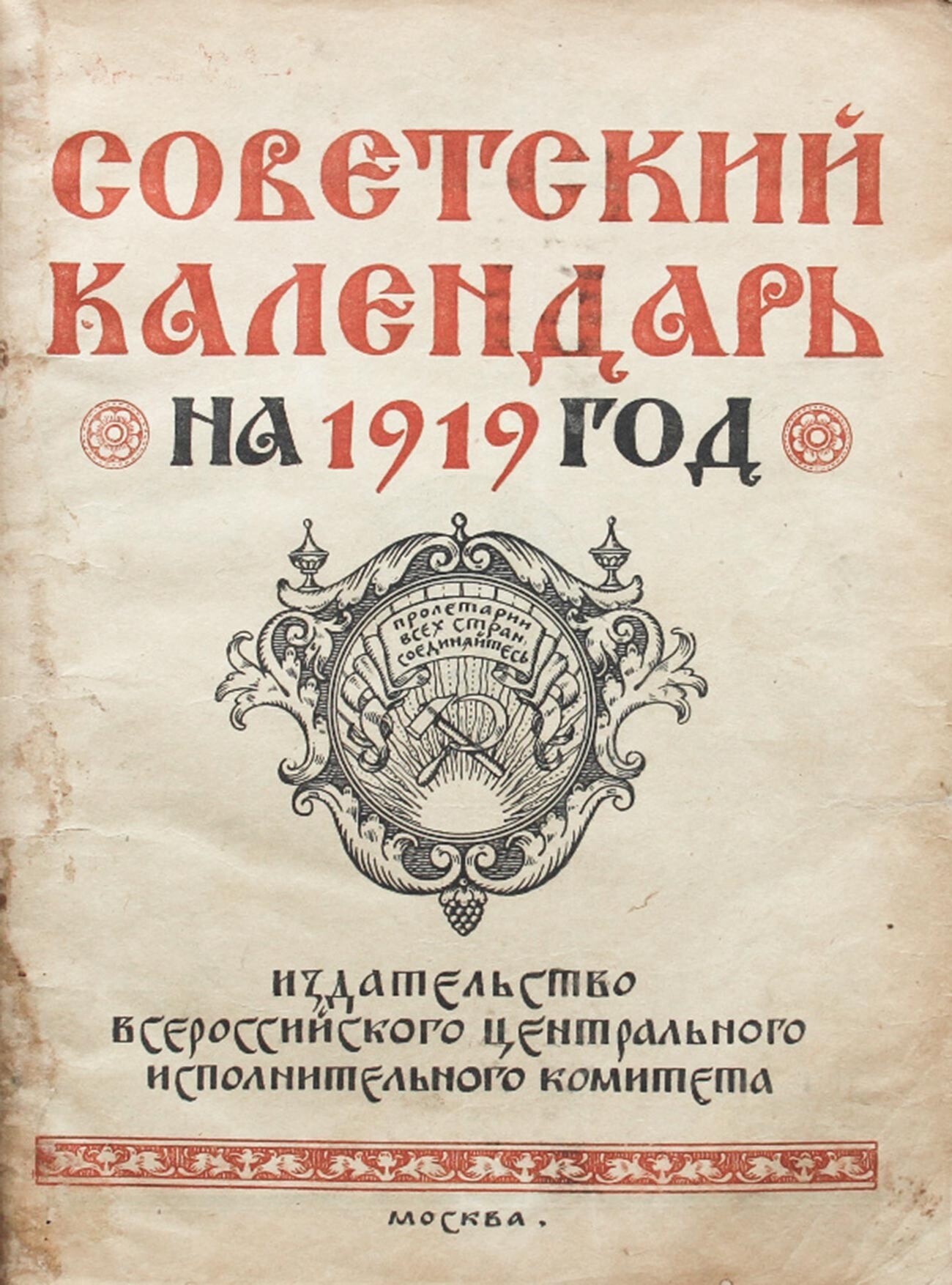

A cover of a Soviet calendar

Public domainHowever, Peter didn’t adopt the Gregorian calendar in the course of this reform – because it was created by Pope Gregory XIII, a Catholic, and the Russian Orthodox church at the time strictly opposed Catholicism. The Russian church stayed with the Julian calendar. Between 1700-1918, Russian and European calendars differed by more than 10 days.

In 1918, the Gregorian calendar was adopted by the Bolsheviks. By the beginning of the 20th century, the difference between the Julian and Gregorian calendars was 13 days. On January 26th (Julian calendar), 1918, the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin signed a decree that introduced the Gregorian calendar in Russia: after January 31st, Old Style, February 14th, New Style, followed. Just like Peter the Great, Lenin “stole” some time from Russian history, but not as much as Peter did – just 14 days.

Finally, Russia and most of the world started living by the same calendar. However, the Russian Orthodox Church has kept the Julian calendar. Because of this, the Orthodox New Year still starts on September 1st, Julian calendar (September 14th, Gregorian style).

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox