There was a case in the early years of Queen Elizabeth II’s reign, when she had to give a pardon to a couple of Soviet deep cover agents. On September 23, 1969, she signed two acts regarding Peter and Helen Kroger. There, Her Majesty admitted they were convicted for secret transmission of information that broke the Official Secrets Act 1911, but ordered to release them the next day after her pardon issue. By that time, they had served eight years of their sentences.

The agents’ true names were Morris and Lona Cohen, but nobody in the UK knew that. Soon, they were used in an exchange for Gerald Brooke, who was convicted in the USSR for spying for the UK. A month after their release, the Cohen couple arrived in Moscow via Warsaw.

Russian spies Morris and Lona Cohen leave London's Heathrow Airport on a BEA flight bound for Warsaw, 24th October 1969.

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesActually, the USSR wasn’t their homeland: Morris (born in 1910) was a son of Russian Empire immigrants and Lona (born in 1913) - a daughter of Polish ones. They were both born in the U.S. Morris recalled he had dreamed of the USSR since his childhood: “I wished to see the motherland of my ancestors with half an eye. As I grew older, this wish became stronger.” His and Lona’s destiny was to live there one day. Yuri Andropov, who was the KGB (‘Committee for State Security’, a Soviet organization that was, in particular, in charge of foreign intelligence services) head at the time, helped the Cohens become citizens of the USSR.

How could it happen that two Americans became Soviet agents? Their political ideas played a key role there. Morris was a dedicated antifascist and communist, so, in 1937-1938, he fought on the side of International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. There, a stationery agent named Alexander Orlov noticed Cohen and invited him to work for the NKVD (‘People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs’, a notorious organization in charge of foreign intelligence). Orlov wrote a report about Morris to Moscow saying: “I’m sure he was driven not by love of adventure, but by his political ideas.” Morris was given a codename ‘Luis’ and returned to the USA as a Soviet agent.

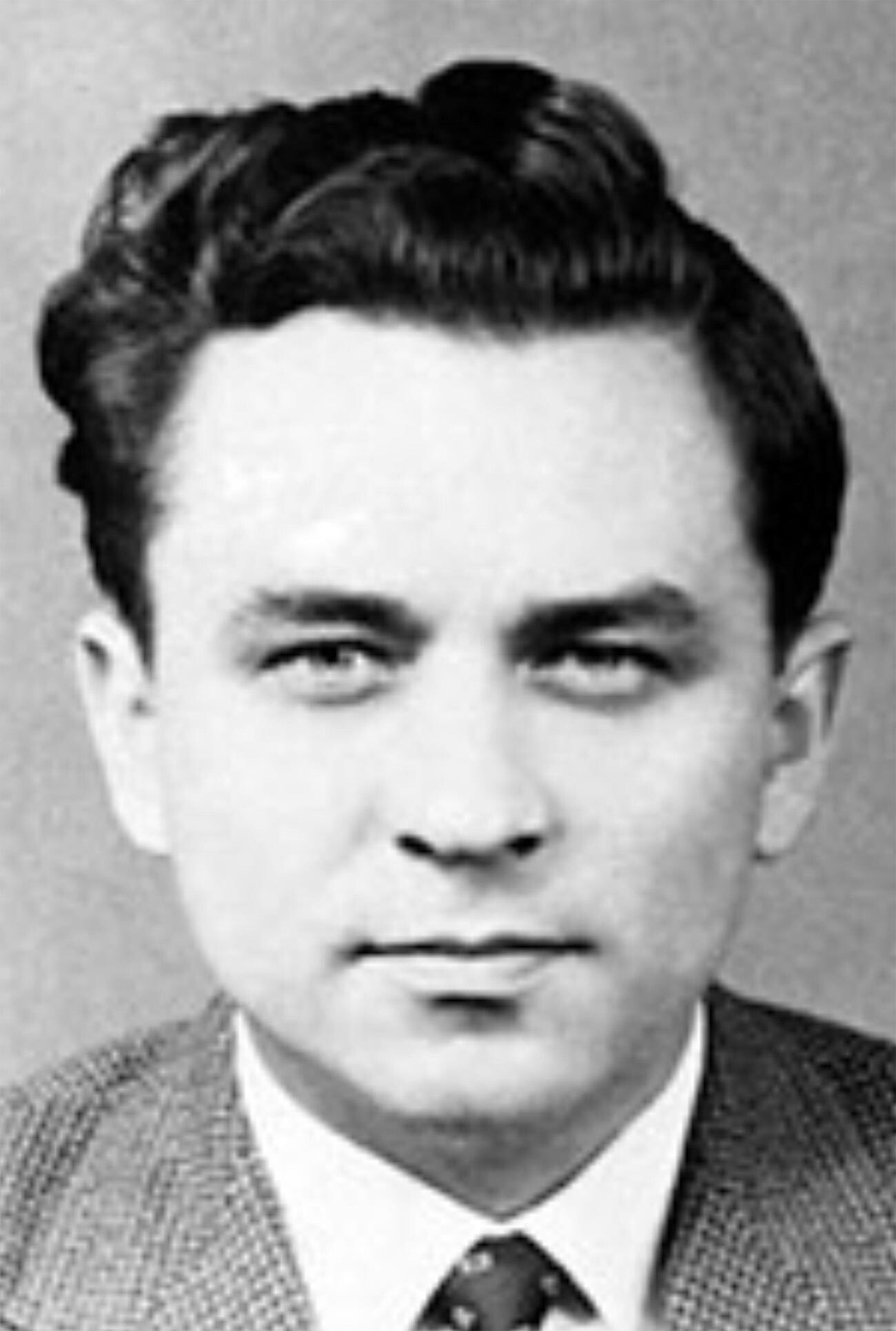

Morris Cohen.

Public domainEven before Morris went to Spain, he met Lona (full name - Leontine Theresa) Petka, also a communist, at an antifascist rally in New York. They got married in 1941. Lona soon began to guess the secret work Morris was doing. He recalled: “Then I couldn’t decide for a long time whether I had to involve Lona into cooperation with Soviet intelligence or not. Of course, I understood there was no sense in playing hide-and-seek.” Lona became a deep cover agent, too, and received the codename ‘Leslie’.

Lona Cohen.

Press PhotoThe Cohens were very talented as recruiters. Their group was called ‘The Volunteers’, because the Americans worked for the idea and accepted only the money that was required to perform their operations. Before World War II, the couple had the task of getting a draft of the newest aircraft machine gun, but they instead got in contact with a plant worker, who even gave them the gun itself, piece by piece. It was sent to Moscow with the help of the Soviet embassy.

In 1942, Morris was called up for military service and sent to Europe to fight the Nazis. Lona then worked with the Manhattan project informers. Morris involved a scientist from the Los Alamos nuclear weapons laboratory, who was codenamed ‘Perseus’. Lona had to meet him in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to obtain some secret documents and then to deliver them to the agents in New York. When she was boarding the train to New York, the police suddenly started checking everyone’s luggage. The documents were hidden in a Kleenex box. Lona pretended to have a runny nose and took the box out. Colonel Dmitry Tarasov recalled: “When they started looking through her things, she handed that box directly in the checker’s hands. She started fumbling in her things herself and did it until the train began to move,” The police helped her get onto the train and gave her back the Kleenex box - nobody even looked at it.

When Morris came back from World War II, the Cohens continued their activities together. They cooperated with agents William Fisher (‘Mark’) and Yuri Sokolov (‘Klod’) until 1950, when the situation had become dangerous for the Cohens - they were close to being disclosed like many Soviet agents were at the time. Sokolov tried to persuade them to leave for the USSR. He recalled: “The Cohens’ safety was doubtful. In the heat of the moment, they [the American officials] might not just arrest them, but do whatever they wanted <...> we had to take measures, save them, evacuate them from the country.”

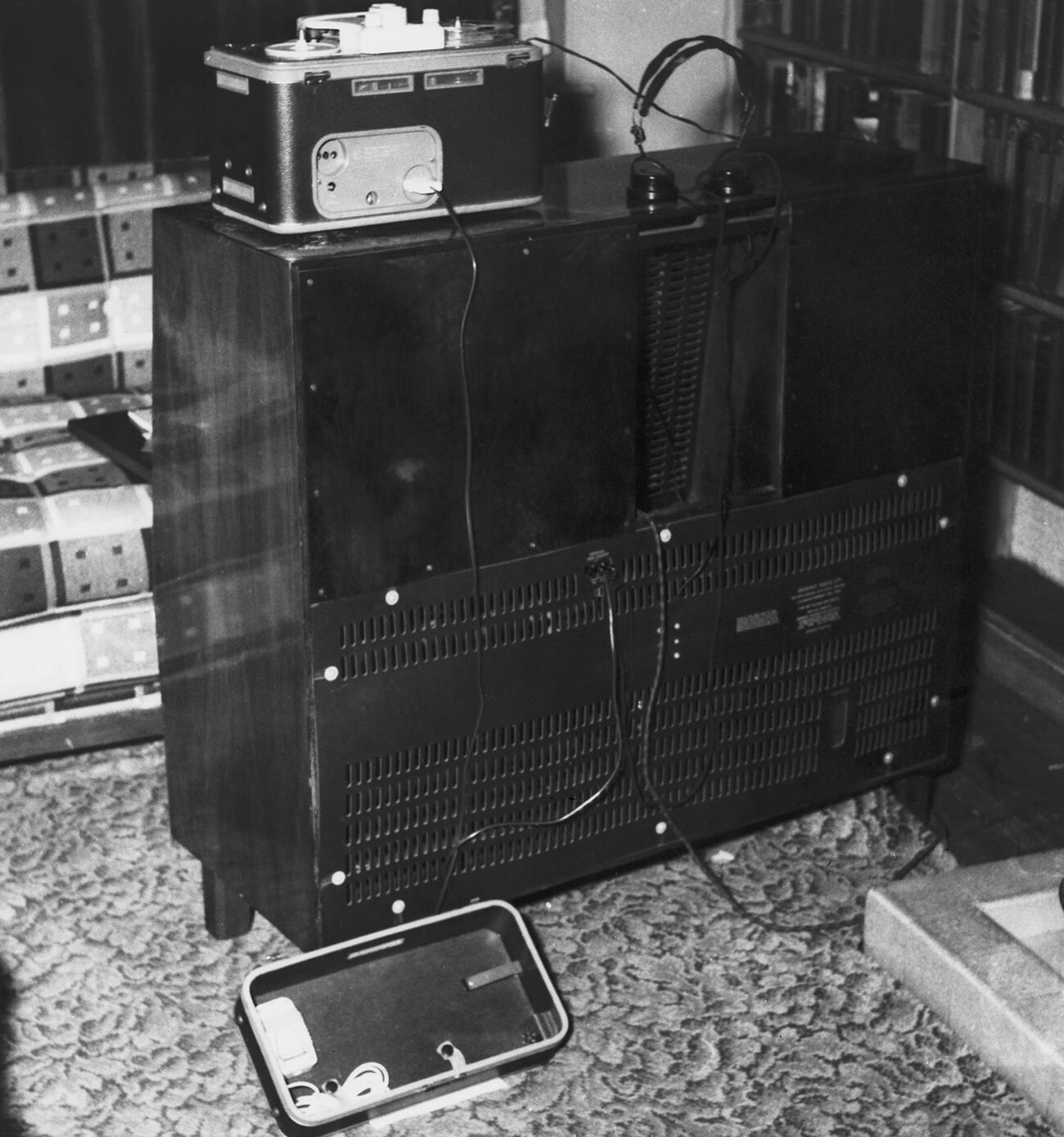

Spy equipment.

Keystone/Getty ImagesAt first, the Cohehs went to Mexico with documents saying they were the Sanchez couple. Then, they had to make a long way through Europe using the last name ‘Briggs’. Suddenly, they were stopped at the German border for an identity check. Lona’s temper frayed. She caused a scandal, shouting at the Germans: “Who, at the last, won the war - the U.S. or you? You have no right to halt an American delegation!” Finally, the passport control officer let them continue their way.

It was their first time in the USSR, but the Cohens didn’t stay there long. They went through additional agent courses and wanted to return to the secret work.

In 1954, the Cohens were sent to the UK as liaison people for a Soviet agent named Konon Molody (‘Ben’), who was known there as a rich Canadian businessman named Gordon Lonsdale. The couple used the aliases ‘Peter’ and ‘Helen Kroger’ from New Zealand. The KGB dubbed them ‘The Cottagers’. They got a small house near the British Air Force’s Northolt base and Morris bought a secondhand bookshop as cover.

A Hillman police car in the driveway of Cohen's bungalow in Ruislip, 9th January 1961.

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesThe main goal of Ben and ‘The Cottagers’ was to explore the secrets surrounding the main base of the British Air Force. They found out political, strategic and technical information; for example, concerning missiles and underwater echo-sounders. The archive documents of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service say they were one of the Soviet intelligence most successful teams. Vasily Dozhdalyov, an agent who worked with Molody, recalled: “Moscow knew the British submarine force as well as Elizabeth II did.”

Molody (1922-1970), Soviet Intelligence Officer.

Legion Mediahttps://phototass4.cdnvideo.ru/width/1020_b9261fa1/tass/m2/uploads/i/20200630/5623435.jpg (Konon Molody)

Their work suddenly came to an end after the betrayal of a Polish agent named Mikhail Golenyovsky, who started to cooperate with the CIA and to pass them everything he knew about the Soviet agents. Molody and the Cohens were arrested in 1961. It was unexpected, so the police found lots of radio equipment in Morris and Lona’s house. Konon tried to take all the blame and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Despite the efforts of Molody, Morris got the same jail time, while Lona was sentenced to 20 years.

The Cohens after the release from their prisons.

Jeremy Fletcher/Getty ImagesThe Cohens felt frustrated and suffered health problems in their respective jails, but they were allowed to write letters to each other. In one of them, Lona wrote: “All we can do is to set our teeth and continue. I know it’s difficult, but we have no choice.” They refused to cooperate with MI6 and disclose any of their secrets until their release in 1969.

Commemorative stamps with Lona and Morris Cohen.

Public domainIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox