The Mongol-Tatar invasion of the Russian lands that happened in 1237-1241 was a total catastrophe – the low-organized forces of the Russian princes couldn’t really oppose the seasoned Mongol-Tatar army that had come all the way from the other side of the known world.

The invaders burned Russian churches and monasteries, just like they burned Russian towns and villages. “Many holy churches were burned and monasteries and [their] villages were burned and their property taken from them,” the Russian Chronicle says. “Monks and nuns and the priest were captured and slashed with swords and some of them shot with arrows and burned alive.” For Mongol-Tatars, it was a usual tactic of total war. At the time, the Golden Horde was mostly pagan and inside the Mongol-Tatar territory, different religions were professed. So in the lands of Rus’, the Mongols didn’t wage any religious war.

The Mongol-Tatar cavalry attacks (reconstruction).

Sergey Bodrov Sr./«STV» cinema production company, 2007Soon, the Mongols noticed it was better to spare Russian religious institutions, as Russians had a great respect for their Orthodoxy. In 1239, two years into the invasion, near Chernigov, “they spared a bishop, brought him to Glukhov (a nearby town – ed.) and let him go”. As the invasion ended, the Mongols took a political course to communicate with the Russian Orthodox church.

Tatar baskaks (taxmen) coming to a Russian village to receive tributes. ("Baskaks," by Sergey Ivanov, 1909).

Sergey IvanovIn 1259, when Mongol-Tatars made Novgorod and Pskov lands pay them tributes, they spared the toll for all the Orthodox clergy and monasteries of the region. Two years later, in 1261, the Russian church sent a permanent envoy to the Golden Horde.

In 1267, Metropolitan Kirill II of Kiev traveled to the Golden Horde to receive a “jarlig”, a document proving his authority as a Metropolitan of the Russian church. He received it from Mengu-Timur – he and Kirill II were close correspondents and political aides to each other. Under the Mongol invasion, Russian princes, as well as Metropolitans, were obliged to receive “jarlig” credentials.

Metropolitan Kirill II travels to Chernigov. From Russian Illustrated Chronicle, 16th century.

Public domainHowever, the Metropolitan had even more rights than any of the princes – he could, for example, contact Constantinople without consent from the Mongol administration. By the end of the 13th century, the Russian church got all its lands and villages back from the Mongols. The Russian church, thus, became an almost autonomous power and administrative structure in the Russian lands.

The Peter and Paul Church, Smolensk, 1146. One of the few Russian churches dating back to the times before the Mongol-Tatar invasion.

Legion MediaTuda Mengu was the Khan of the Golden Horde in 1280-1287 and the first to convert to Islam. The next two rulers still professed some traditional beliefs. Öz Beg (Uzbeg) Khan started his reign in 1313 and, in 1320, converted to Islam.

Inside the Golden Horde, Uzbeg Khan tried to make Islam the official religion (against the opposition of the Horde’s elite). But he apparently didn’t have any intention to convert the Russians to Islam. He even made his sister Konchaka marry Yuri Danilovich of Moscow, a Russian prince. Subsequently, Konchaka was later poisoned in captivity, during a local war between Yuri and another Russian prince Mikhail. All of them were later killed in the Horde at Uzbeg’s order. Meanwhile, the Russian church didn’t suffer any losses.

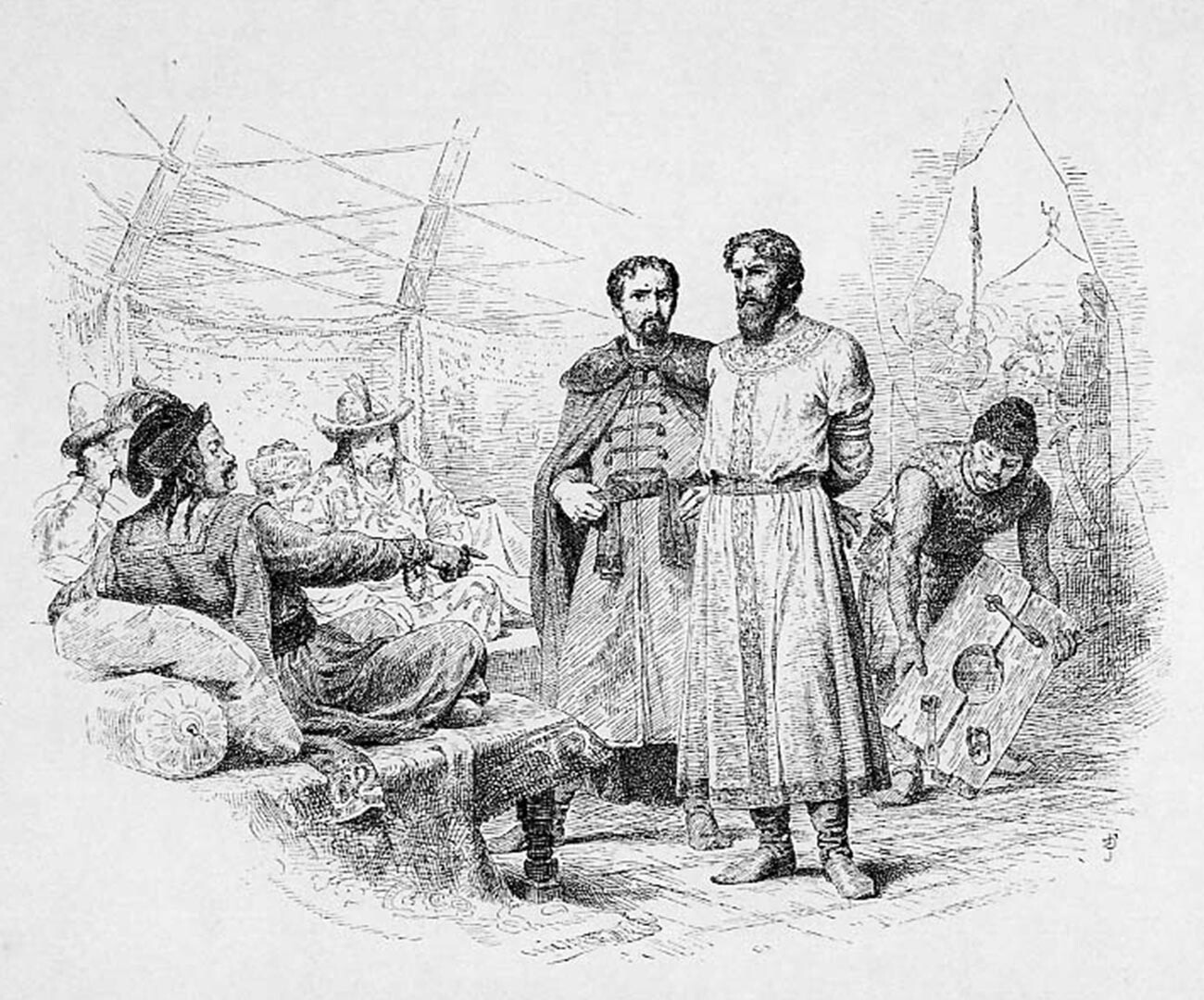

Prince Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tver at the court of Uzbeg Khan. Uzbeg Khan orders his servants to capture and murder prince Mikhail for poisoning his sister Konchaka.

Vasiliy VereschaginIn 1313, Metropolitan Peter of Kiev traveled to the Golden Horde, where he was warmly and respectfully received and issued a jarlig confirming the Orthodox church’s privileges, meaning the fact that all the taxes and the tributes were levied from it. It was obvious that for religious Russians, including their princely elite, security and well-being of their church meant very much and Uzbeg Khan apparently understood it very well.

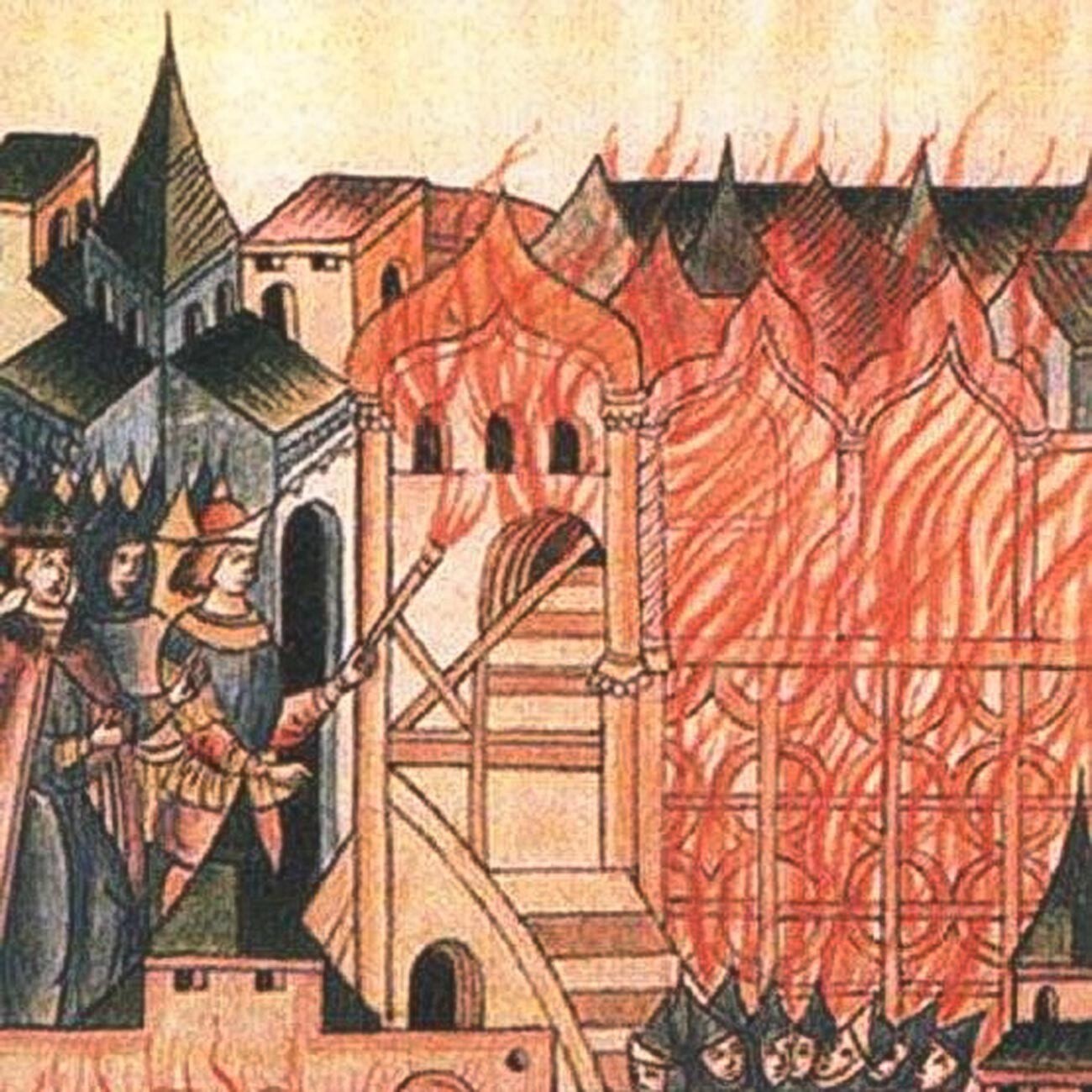

Ironically for the Mongol Khans, it was the Russian Orthodox ideas that inspired the struggle against the Mongol invasion. In Tver in 1327, a senior Mongol official, Cholkan, Uzbeg’s cousin, and his guards were attacked for “persecution of Christians” and many other Mongol Tatars, such as traffickers, merchants and horsemen killed all over the town of Tver. Rumors went around that Cholkan came to convert the Tver people to Islam – that enraged the public even more.

The Tver uprising of 1328 as seen in a Russian Illustrated Chronicle, 16th century. In this picture, the people of Tver are shown burning the palace with Cholkhan, Uzbeg Khan's cousin, inside it.

Public domainCholkan was eventually burned alive, locked inside a palace. The Tver riots were fiercely suppressed by the Mongol Tatars, aided by Prince Ivan Kalita of Moscow. But these clearly anti-Islamist, xenophobic events of the Tver riots finally diverted Uzbeg Khan away from the thoughts of converting Russians to Islam, if he still had any.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox