Was emigration from the USSR ever possible?

Throughout its lifetime, the Soviet state aspired to control emigration from the country and used it as a “carrot and stick”. While it sent some of its citizens out forcibly, for others it made it impossible to leave.

The first exodus

Since the Russian Revolution and subsequent formation of the new Soviet state, up until its eventual collapse in 1991, there had been five different periods of mass migration from the country, also known as “waves”.

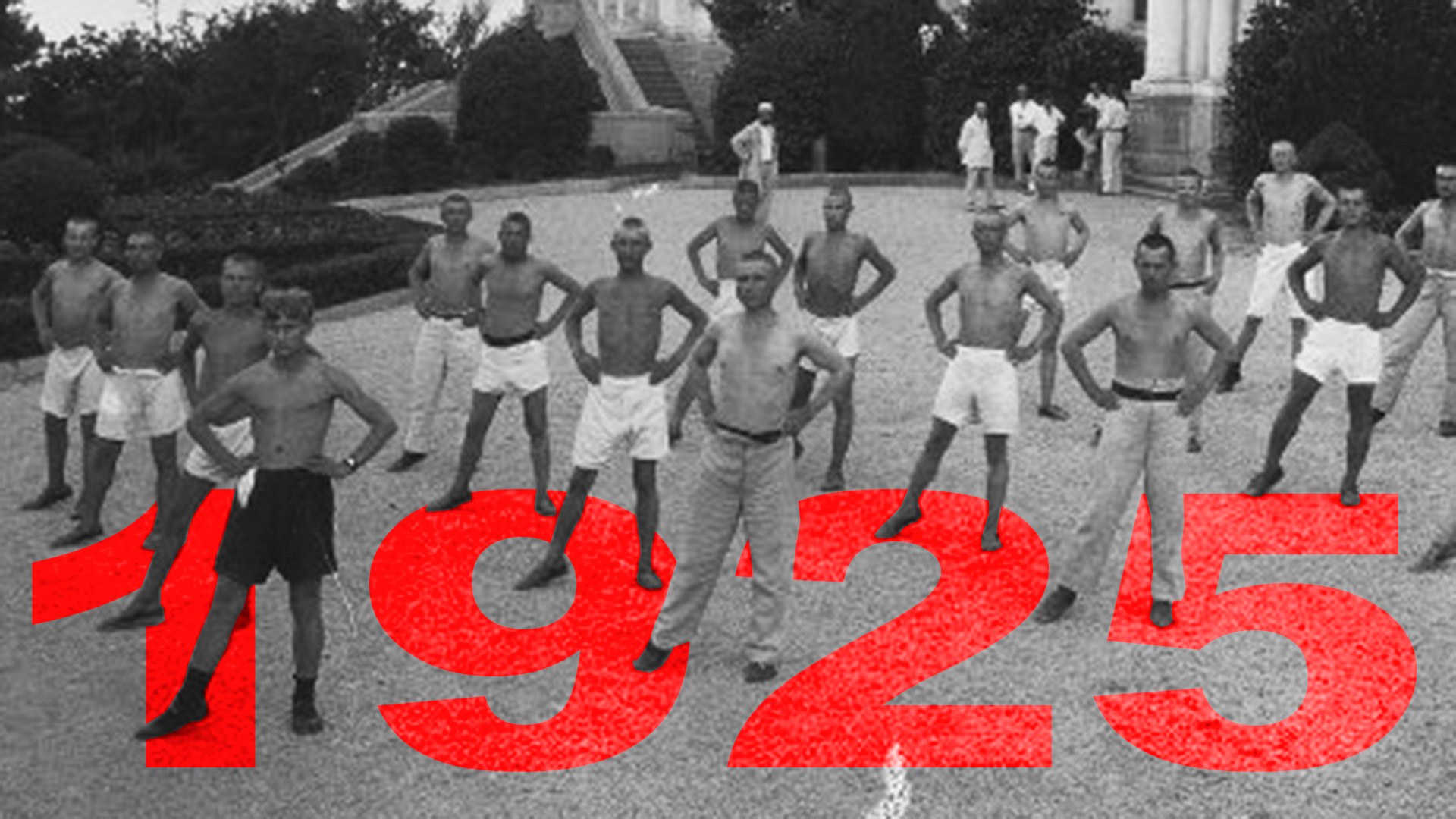

By the time the Soviet state was formed in 1922, a massive emigration of the so-called White Emigré — mostly those Russians who opposed the formation of the Bolshevik government — hit the newly formed state.

The first exodus was simultaneously the most massive in Russian history and the most devastating for the emerging state in the economic and cultural sense. The number of people who fled Russia after the Red Army finally defeated the opposing side is roughly estimated at 2 million people.

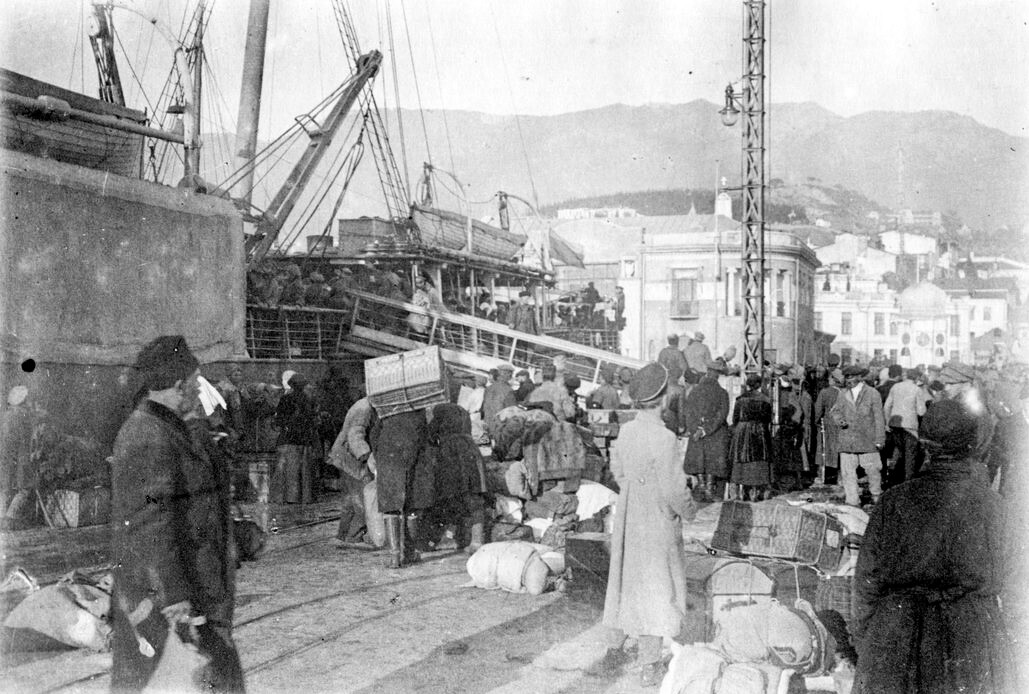

Evacuation of the Whites via a port in Crimea.

Evacuation of the Whites via a port in Crimea.

A lot of people who excelled at their craft – including Russian intelligentsia, military officers, statesmen, businessmen, landowners and intellectuals of all kinds – chose to part ways with their motherland forever. Many of them successfully reinvented themselves in other countries. “Father of aviation” Igor Sikorsky, who successfully designed helicopters for the U.S. president after he had relocated to the country, is just one example.

The American Red Cross ship "Steamer Sangammon" carrying Russian refugees from Novorossiysk to the island of Proti, 1920.

The American Red Cross ship "Steamer Sangammon" carrying Russian refugees from Novorossiysk to the island of Proti, 1920.

After this massive outflow of the population, the borders of the Soviet Union closed tight, making emigration an unattainable dream for many.

Behind the Iron Curtain

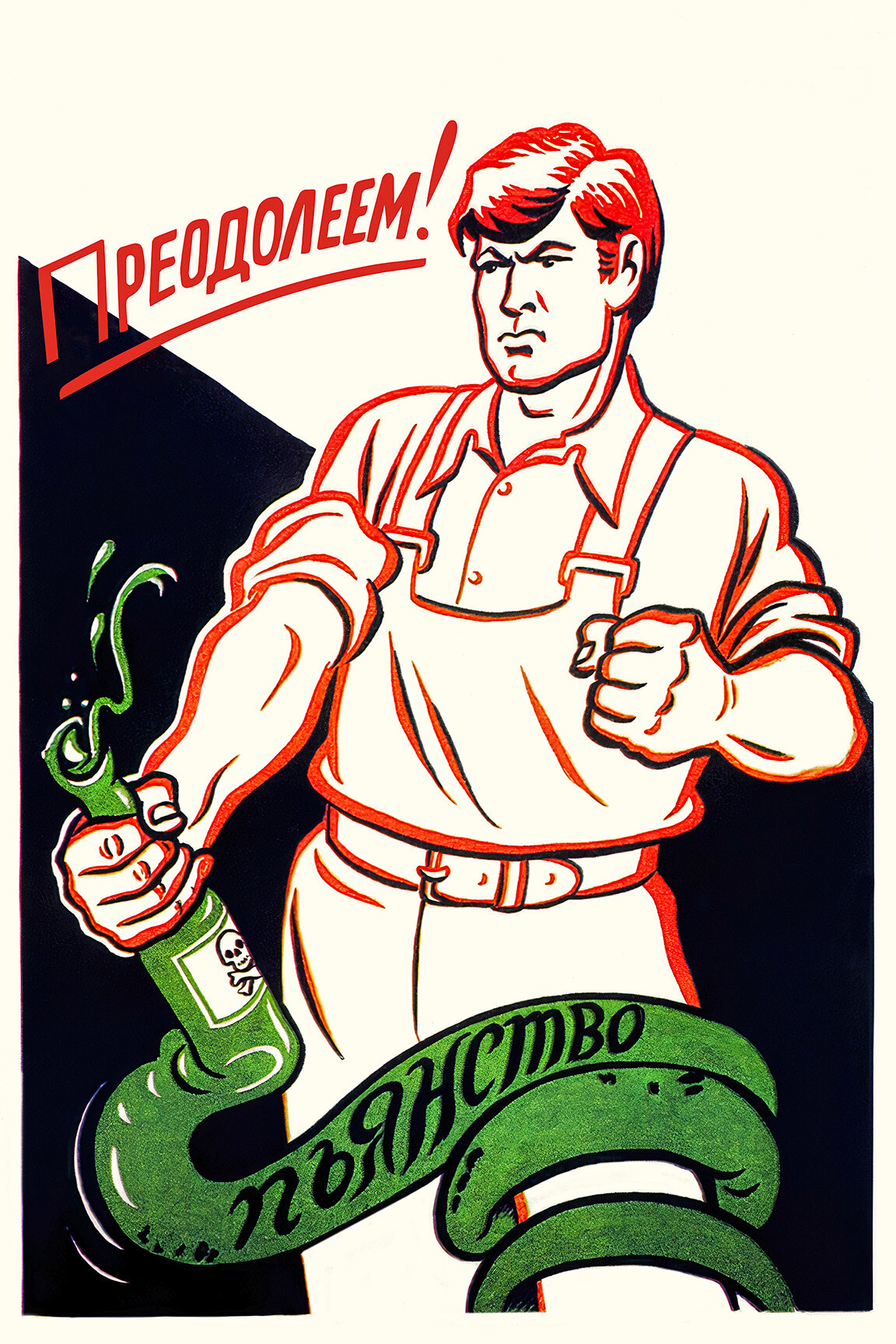

While it was still possible to leave the Soviet Union in its early days, the country was sealed off from the rest of the world by the late 1920s. For decades after that, there were no emigrants in the eyes of the Soviet authorities… there were only defectors.

A poster saying "The enemy will not pass! The borders of the homeland are guarded by the entire Soviet people."

A poster saying "The enemy will not pass! The borders of the homeland are guarded by the entire Soviet people."

In 1935, Soviet authorities, under the leadership of Joseph Stalin, introduced unprecedentedly harsh measures to eradicate the very thought of emigration in the minds of the Soviet people. Under the new law, fleeing across the border was punished by death. Moreover, relatives of the defectors were also held accountable under criminal law.

The harsh law was narrowly aimed at high-ranking politicians, diplomats and intelligence officers – many of whom were stationed abroad in the line of their duty – as the majority of the Soviet population did not have the means to flee the Soviet Union even if they wanted to.

Despite the severe sanctions, this period of Soviet history was marked with scandalous defections of key figures in both the Soviet political establishment and security apparatus. Stalin’s personal secretary Boris Bazhanov became the first major defector from the Soviet Union, paving the way for others: like Soviet intelligence officer Igor Gouzenko whose revelations triggered a wave of the red scare in the West, Stalin’s notorious hitman Bohdan Stashynsky, head of the Soviet Secret Police branch in the Far East Genrikh Lyushkov, who fled to Tokyo before the start of World War II, Under-Secretary-General of the UN Arkady Shevchenko, who asked the U.S. Ambassador for asylum in 1975, and notorious double-agent Oleg Gordievsky, who worked for British intelligence MI6 before he fled the USSR in 1985.

Arkady Shevchenko, the Soviet diplomat to seek asylum in the U.S., takes the oath of American citizenship in Washington, Feb. 28, 1986.

Arkady Shevchenko, the Soviet diplomat to seek asylum in the U.S., takes the oath of American citizenship in Washington, Feb. 28, 1986.

Some of the defectors were murdered abroad by Soviet secret agents, while others lived to old age, sometimes in permanent fear of reprisals. None of them have ever seen their country ever again, however.

After Stalin’s death and subsequent annulment of the law which criminalized the family of the defector, many prominent Soviet figures preferred not to return to the Soviet Union if they had a chance to travel abroad. Many prominent Soviet athletes and cultural figures became so-called “non-returnees”, the term used to describe Soviet people who declined to return to the USSR from a trip abroad.

Trapped in the USSR

As emigration finally became legalized in the late 1960s and early 1970s, people of mostly non-Russian ethnicity saw this as an opportunity to forever leave the Soviet realities behind.

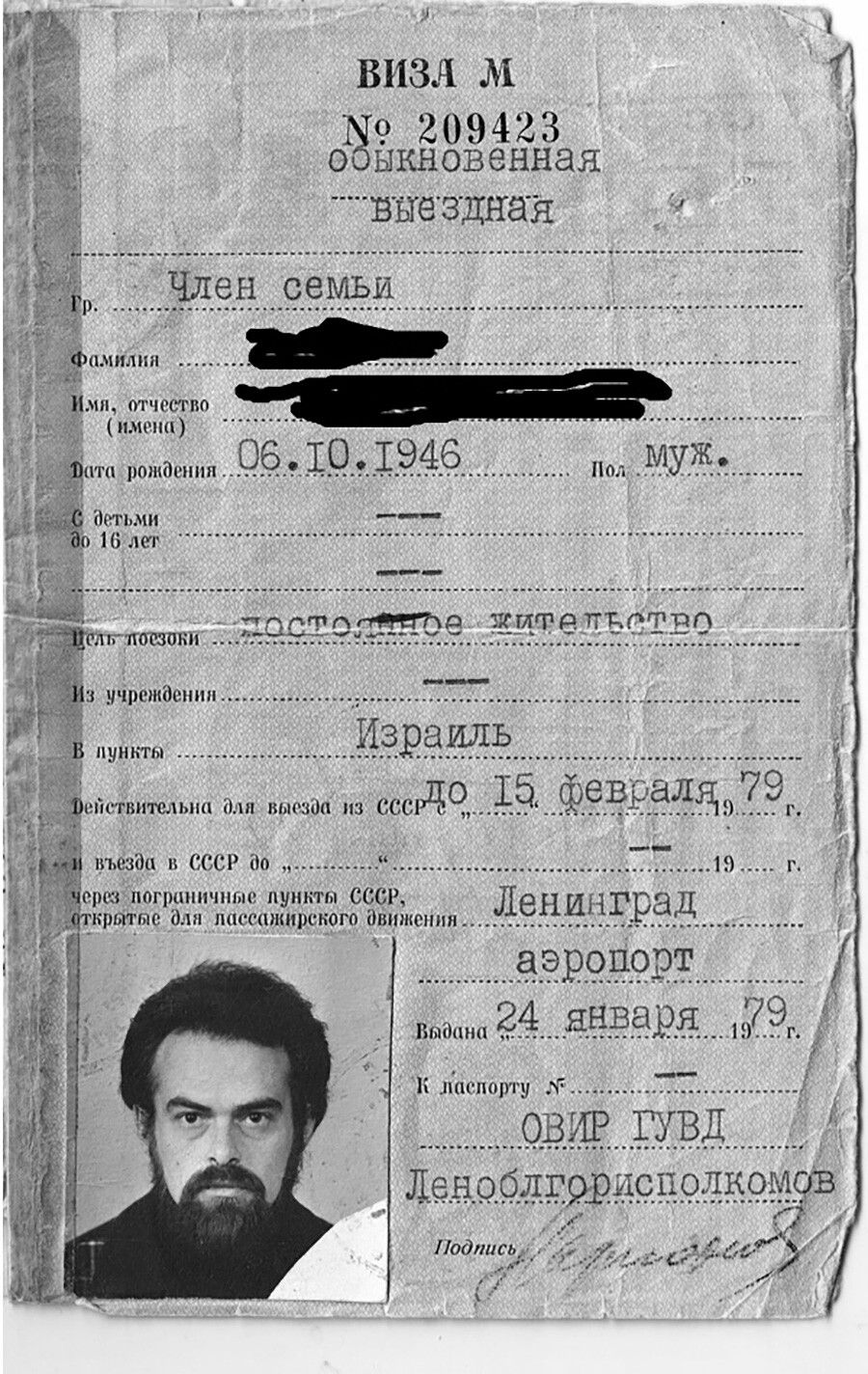

However, fearing the massive outflow of the population, which threatened to undermine the image of the socialist world in the eyes of the public, the Soviet government made it necessary to obtain exit visas — formal permission from the authorities to migrate.

Soviet exit visa of the second kind (allowing to leave the USSR permanently).

Soviet exit visa of the second kind (allowing to leave the USSR permanently).

In practice, many people found it impossible to get visas. By the 1970s, the problem became so acute that a new term emerged to denote those who had been refused exit visas — Otkazniki (Eng.: Refuseniks).

Refuseniks protest in 1980.

Refuseniks protest in 1980.

In some cases, the authorities drove people to desperation to such an extent that they were ready to commit despicable acts to find a way out of the USSR.

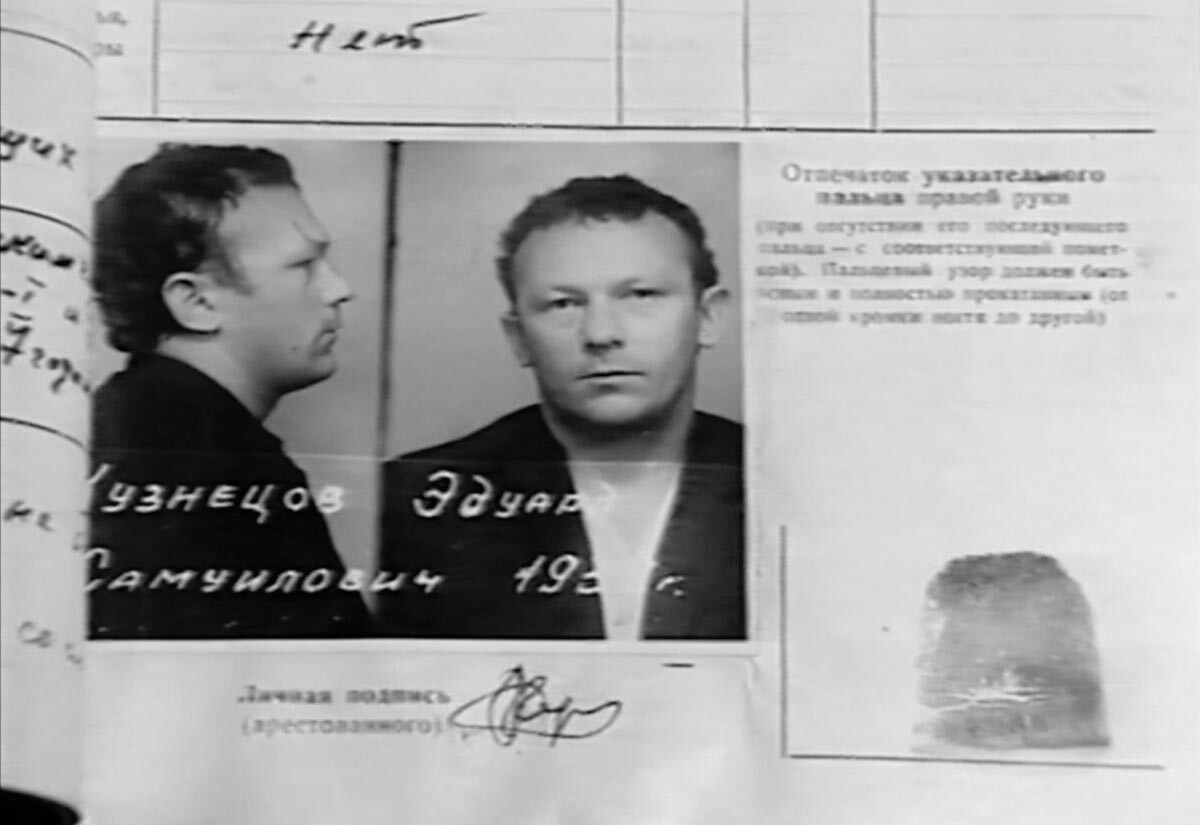

“I had almost no doubt that we would be arrested. But, I thought that after serving my sentence, it would be easier for me to leave the Soviet Union,” said Eduard Kuznetsov, one of the ethnic Jews who conspired to hijack an airplane to flee the USSR in 1970.

A mug shot of Eduard Kuznetsov.

A mug shot of Eduard Kuznetsov.

While some may have been waiting for their exit visas for years, others found themselves in the opposite situation. In the late 1970s, Soviet authorities practiced depriving some of the Soviet citizens of their citizenship in absentia, while they were on a trip abroad. For example, cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and his wife soprano opera singer Galina Vishnevskaya were stripped of their Soviet citizenship while they were abroad.

A lot changed when Mikhail Gorbachev launched the policy of perestroika. As scientific and cultural exchanges with foreign countries expanded and traveling abroad became more frequent, the rules on emigration eased, as well.

Soviet citizens stand in line outside the U.S. Embassy in Moscow for the documents required to leave the USSR. 1990.

Soviet citizens stand in line outside the U.S. Embassy in Moscow for the documents required to leave the USSR. 1990.

Despite the degree of liberalization, however, the underlying principle remained intact: Soviet citizens seeking to emigrate from the Soviet Union had to secure exit visas first. Only after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 were Russians free to migrate to a country of their choice.