In the late 15th century, Europe was in the grip of madness. Thousands of bonfires raged, used by locals to burn women and men suspected of witchcraft. A tiny sliver of suspicion was enough to warrant an accusation of complicity with the devil and send the person to be tortured, usually resulting in a death that was often just as gruesome.

Witches and warlocks were sent into the fire in neighboring Russia, as well. However, the witch hunt here did not achieve such systematic dimensions and mass character as it had in Europe. How come?

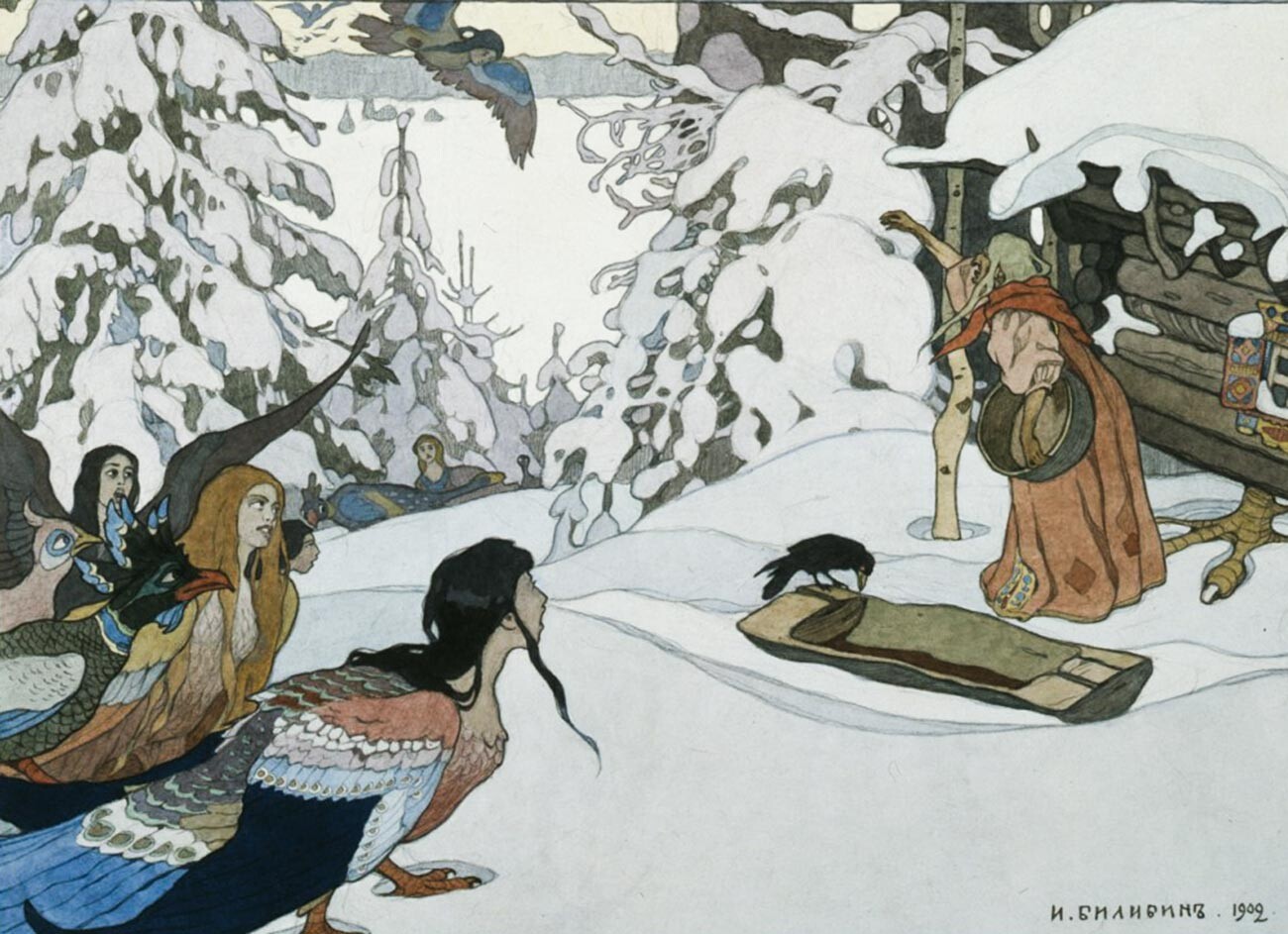

Baba Yaga.

Ivan BilibinMass delusions about dark magic - the way they were experienced in Europe - didn’t occur in Russia, chiefly because of the path of development taken by the Orthodox Church. Demonology as a complete science did not find a home here; Catholics and Protestants borrowed theirs from antique times. Therefore, there were no monumental philosophical-religious treatises on witches and demons to speak of in Russia - such as Johannes Nider’s ‘Formicarius’, ‘The Scourge of Heretical Enchanters’ by Nicholas Jacquier and, of course, Heinrich Kramer’s and Jacob Sprenger’s ‘The Hammer of the Witches’.

There was, likewise, no fanaticism in Eastern Christianity with regards to the treatment of women as a “vessel of evil” and “the embodiment of sin” - with the woman being imbued with such qualities, due to “a lack of intelligence” and, therefore, supposedly more prone to going against faith and making deals with the Devil, unlike a man. It should also be noted that most persons being accused of using magic in Russia were, in fact, men.

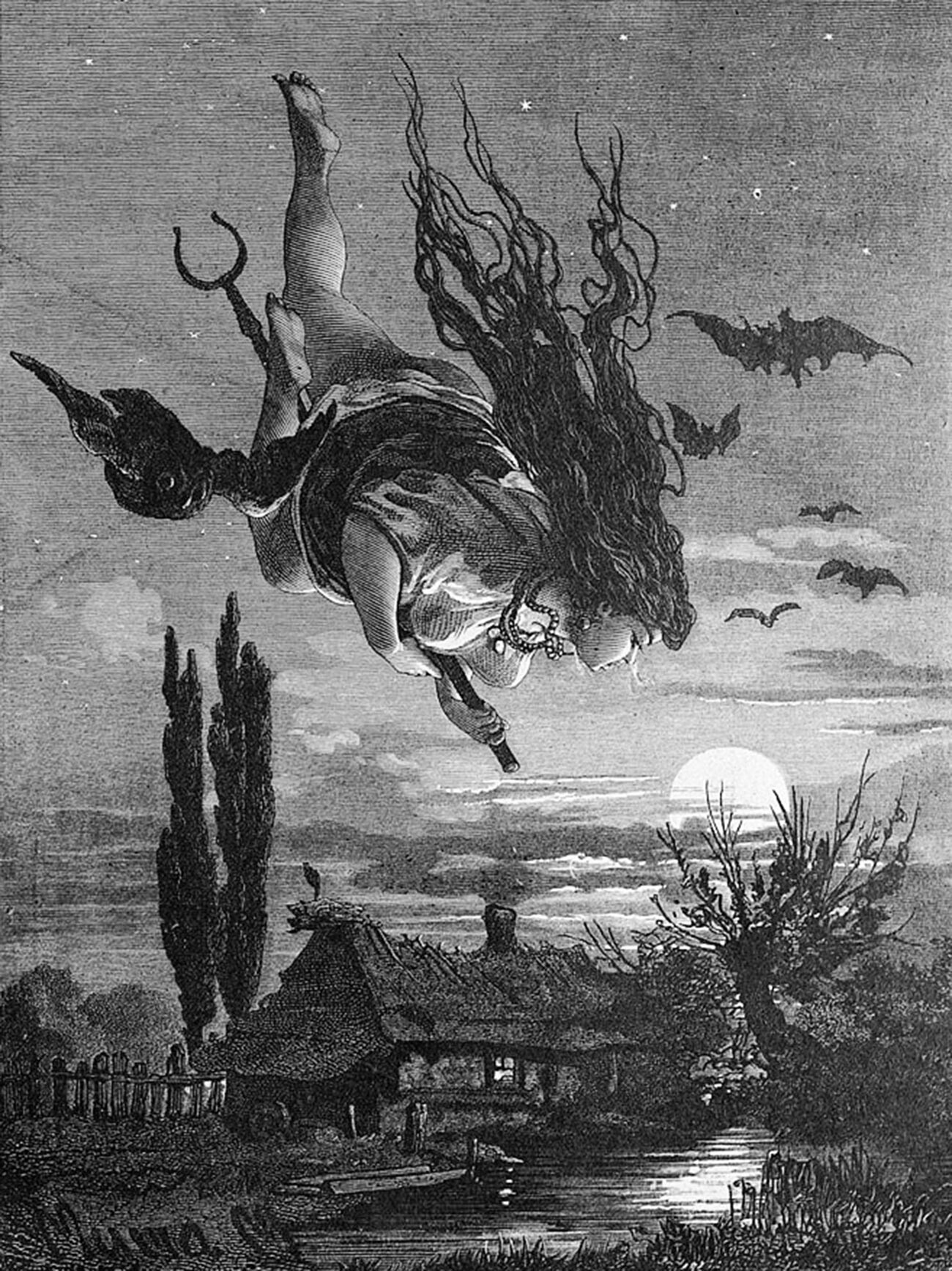

Witch. Picturesque Russia, 1897.

Public DomainWarlocks and witches were not seen in Russia in an explicitly negative light - as adherents of Satan, who received their powers from him. They could well have been born with it, with there being no direct conceptual link to the Devil.

Christianity arrived in Rus’ later than it did in the West and the rudiments of pagan worship continued to linger there for a longer period. Witches, healers, herbalists and soothsayers were often seen as descendants of the servants of pagan cults - the Volkhvs or the Magi. They were feared, but people would frequently consult them with pleas to heal their loved ones or their livestock. A warlock would often be seen at weddings, in order to not risk him holding a grudge against the newlyweds and to defend their union from the dark forces.

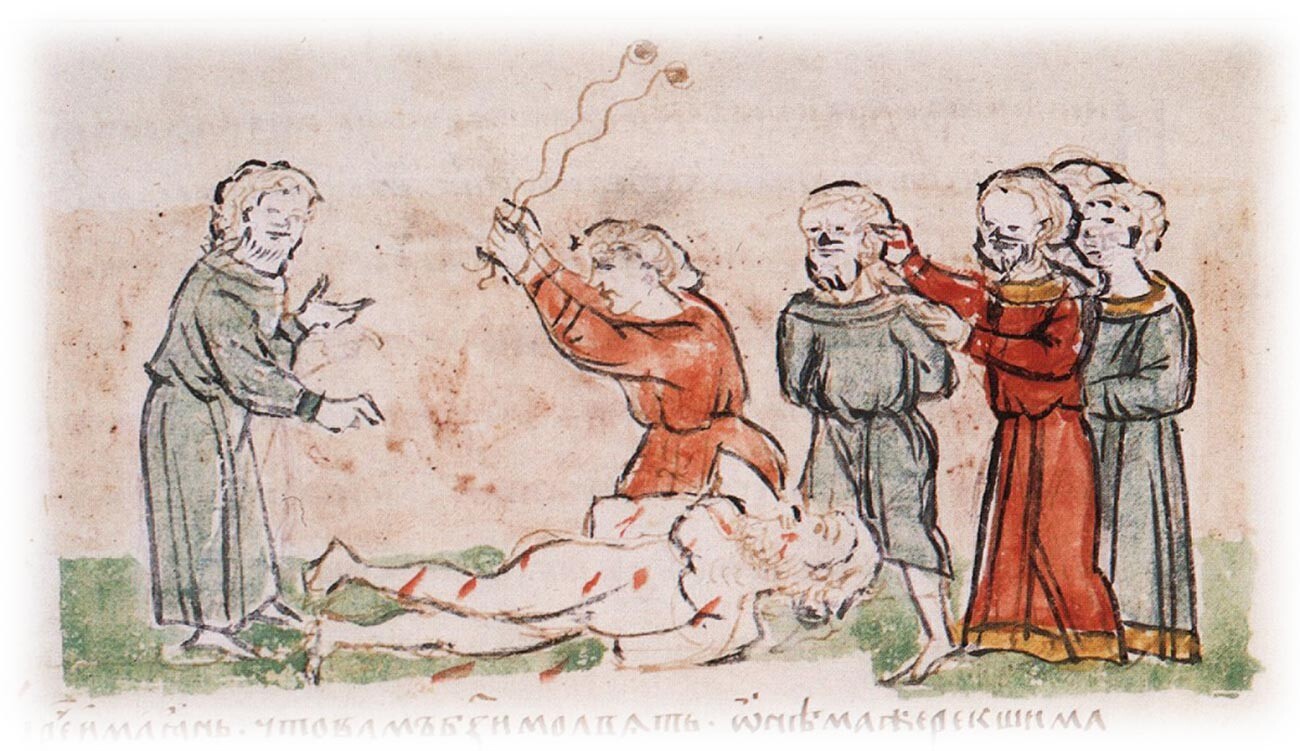

Oleg meeting the Volkhv.

Viktor VasnetsovWizardry, however, was still treated by the state and the Church as a sin and was targeted and persecuted in every possible way. The exception being that these witches and warlocks would not be so readily sent to be “cleansed” by the fire, the way they would in Europe. As long as they lived their lives without stepping on anyone’s toes and there were no accusations of curses, they were often simply left alone.

However, if things did escalate to a full-blown investigation, it wasn’t the inquisition that took on the job (Russia never had any executive branches of the sort), but the secular authorities - as was the case in Protestant countries. Unlike their Western European counterparts, these bodies were rarely interested in whether the defendants flew on broomsticks or partook in sabbaths. Of prime importance were issues relating to the gravity of damage caused to agriculture and specific victims by way of dark magic.

Punishment of the Volkhvs by the order of Yan Vyshatich. Radziwiłł Chronicle.

Public DomainThe Church did not distance itself from trials. Fearful of the spread of heresy, it was very interested in establishing exactly what books and/or religious paraphernalia were used in conducting the rituals.

For the most part, a witch or a warlock were given rather soft punishments. In 1555’s ‘Sentencing Charter’ of the Troitse-Sergiev monastery, sent out to the lands under its jurisdiction, there was a section detailing how “a buffoon or sorcerer, or an old seer woman, must be beaten, deprived of belongings and kicked out of the domain”.

A sorcerer comes to a peasant wedding.

Vasily MaksimovFrequently, those accused of magic were sent to a monastery, where they were to spend time attoning and re-educating themselves, spending their days in fast and celibacy. During Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich’s reign, in late 17th century, those accused of “ungodly communication with the evil spirits” were sent to Siberia, where they were chained to the walls in local prisons and fed only bread and water.

Magic sometimes incurred far more severe forms of punishment than described above. In 1411, 12 women were burned in Pskov, accused of spreading pestilence. In 1462, in Mozhaisk, near Moscow, boyar (noble) Andrey Dmitrievich and his wife were both burned for alleged sorcery.

Sorceress, 1891.

Mikhail ClodtIn 1497, Ivan III, the Grand Duke of Moscow, received a report that his wife Sofia Paleolog was visited by three “conniving old hags” with a “concoction”. All three were found and drowned in a river.

An entire arsenal of weapons and torture was available to the judges carrying out trials - from rearing people up, through to testing them with fire and piercing the “devil’s markings” - warts and birthmarks. Perhaps, the only thing different from the West was the absence of water torture.

Tsarina Evdokiya Lukyanovna’s (Streshneva) gold embroiderer, Darya Lomanova, had to go through seven circles of hell. She and her friend Avdotya Yaryshkina, together with several Moscow herbalists, were accused of the deaths of two small princes in 1639.

Sorceress, 1867.

Firs ZhuravlevThe women were reared up, with belts being tightened so severely that their limbs were being pulled from their sockets. Their backs were whipped, and they were tortured with fire. Nobody ended up confessing, however. In the end, those who remained alive at the end of the torture, was simply sent off to remote parts of the land.

In 1716, Tsar Peter I wrote in the Military Charter: “If an idolater or magician, or conspirator or otherwise superstitious and blasphemous sorcerer is discovered among military ranks: upon being imprisoned and chained, he shall face corporal punishment and be burned to death.”

The persecution of witches, sorcerers, seers and warlocks in Russia came to an end during the era of enlightened absolutism, as it did in Europe, in the late 18th century.

Prediction.

Sergei SolomkoThen, during the reign of Catherine II, instead of fire, the accused were more often condemned to punishment by whipping and six months of service at a monastery. The cases of “sorcery” themselves increasingly became a subject of comedy in society.

So, in the 1770s, when captain Shmalev of the Tengin fortress in Kamchatka burned a local sorceress in a wooden frame, it was considered an act of untold savagery. Baron Vladimir Shteingel wrote with sadness how, unfortunately, “this action, which harkens back to barbaric times, committed during the reign of such a wise and human-loving empress, was committed by Shmalev with absolute impunity.”

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox