“The tsar summoned me and gave me a goblet filled with wine, from his own hands,” Raphael Barberini, a noble Italian, who, in 1564, brought Ivan the Terrible a letter from Queen Elizabeth of England, wrote. “Immediately after this, the drunkenness hit hard, so, forgetting all decorum and modesty, we all rushed towards the doors… until, at last, we reached the palace porch, from which, twenty paces or more away, the servants with horses were waiting for us. But, when we came down from the porch to get to our horses and ride home, we had to wander through the mud, which was knee-deep and the night was dark, there was no light anywhere, so that we suffered enough, until we could get on the horses.”

The alcohol-fueled adventures described by Barberini were not unique. “Many foreigners, knowing the custom of Russian hospitality, sat down at the table with the alarming thought that they would be forced to drink a great lot,” wrote Vasily Klyuchevsky.

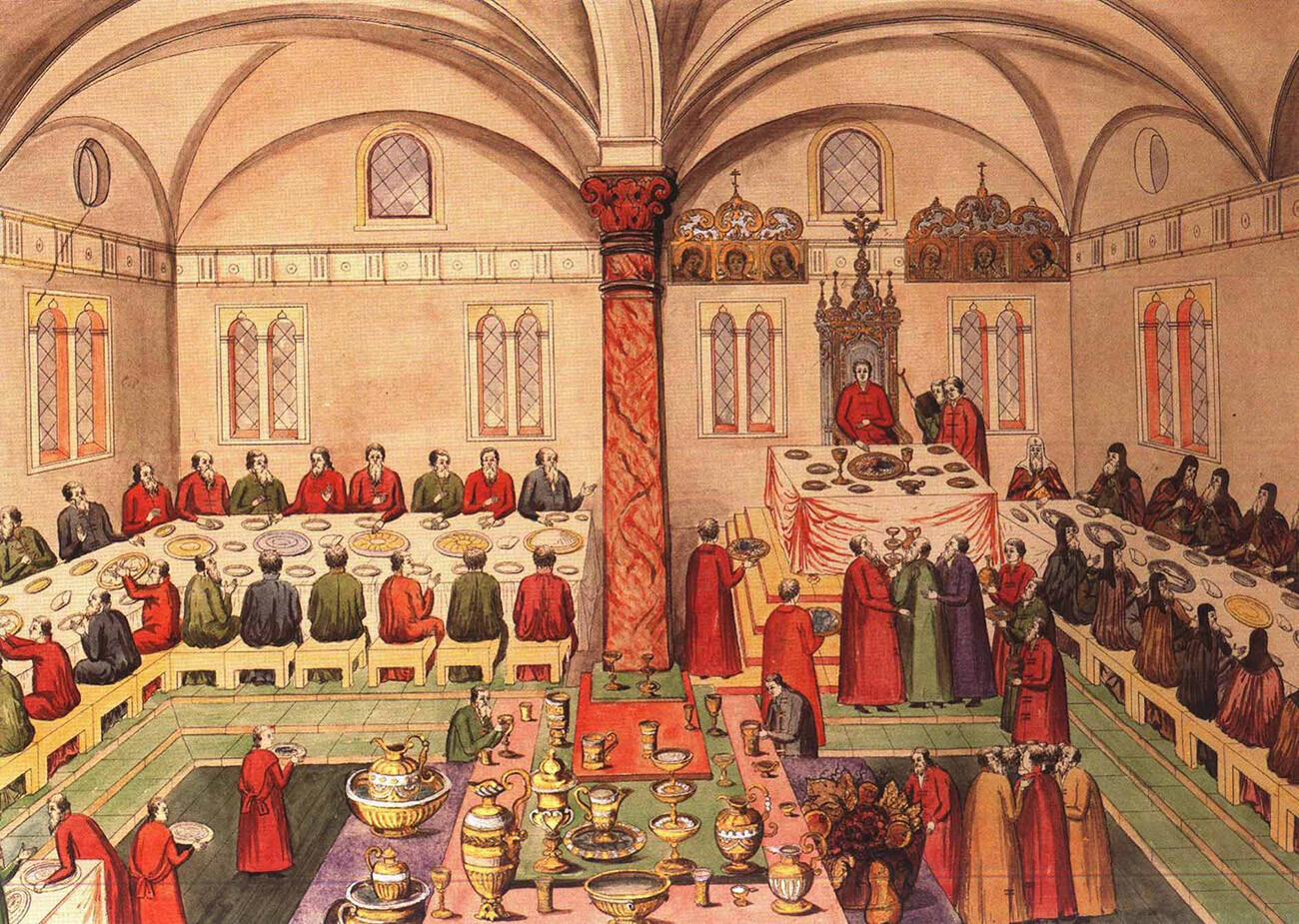

A feast in the Palace of Facets, a 16th-century drawing

Public domainAt first, in the 15th-16th centuries, Moscow princes and tsars greeted every embassy personally. In the 17th century, there were more foreign ambassadors and relations weren’t as equally merry with all foreign states. A meal in the presence of the tsar became a privilege only for the most honorable and respected guests. How this usually happened is described by Andreas Rhode, secretary of the Danish embassy to Russia under Hans Oldeland in 1659.

“Drinks were brought: wine, honey, and vodka, in seven silver and gilded jugs of different sizes and in five large pewter jugs; as for beer, it was brought on a sleigh. When the table was laid, it was all covered in different dishes; and then the envoy was invited to dinner. According to Russian custom, the envoy was offered first of all to drink some very strong vodka from a beautiful charka, set with gold. Then, everyone at the table was poured a large glass of Rheinwein, but, in anticipation of the upcoming toasts, no one has dared to touch it,” wrote Rohde.

A Russian charka (appr. 110 grams)

BKHV (CC BY-SA 4.0)A Russian charka in the 17th century was more than 120 grams, so it is not surprising that after such a start of the meal, the Danish envoy was in no hurry to drink Rheinwein. And what about the Russians themselves? According to the Russian customs of those times, to get drunk at a royal feast was a necessary thing to show respect for the host. As one more guest of Moscow in the 17th century, Austrian diplomat Augustin von Meyerberg noticed: “No one leaves the dining room unless he is carried out [drunk].” By the way, Meyerberg himself was also not a great fan of Russian ambassadorial receptions. On one of his visits, he was a guest of Afanasiy Ordin-Nashchokin, the de facto head of Russian diplomacy. Meyerberg was relieved to note that Nashchokin “with friendly courtesy dismissed the Russian way of drinking and the habit to get drunk” to the delightment of his foreign guests.

However, when dealing with the tsar, to get rid of this burdensome duty for the ambassadors unaccustomed to Russian vodka was not possible – apparently, Russian diplomats set a direct goal to get the foreigners drunk to the point of astonishment.

"The kissing rite," by Konstantin Makovsky. At the end of a feast, the women of the house kiss all the guests goodbye, even if the guests are already quite drunk.

Konstantin MakovskyVodka (bread wine, as it was called in Moscow in those days) was generally the main component of the provisions given to foreign ambassadors. In the 16th and 17th centuries in Moscow, it was still an unusually expensive drink, produced only by the state. This is how much alcohol, for example, was issued to John Merrick, the English ambassador in Moscow under Mikhail Fyodorovich. Each day, Merrick personally received four cups of vodka (about half a liter), a bowl (1.1 liters) of grape wine, three bowls of fermented honey, a bowl and a half of mead and a bucket of beer per day. The nobles accompanying the ambassador received four cups of bread wine (but of a lesser quality than the ambassador), a bowl of honey, three quarters of a bucket of mead, and half a bucket of beer. Even the common servants in the ambassador’s entourage were each given two cups of vodka and half a bucket of beer. Quantities, of course, far more than could be drunk in a day. Why was all this done? Of course, to show the wealth and generosity of the Russian tsar and, also, if possible, to find out what the ambassadors and their entourage might say during such feasts.

The feast for important ambassadors did not end in the royal palace. Since the end of the 15th century, there has been a custom of “drinking the ambassador” right at his ambassadorial court, provided by Muscovites for accommodation of a foreign guest and his entourage. How this happened, describes in detail Sigismund Herberstein, who visited Moscow in the 16th century.

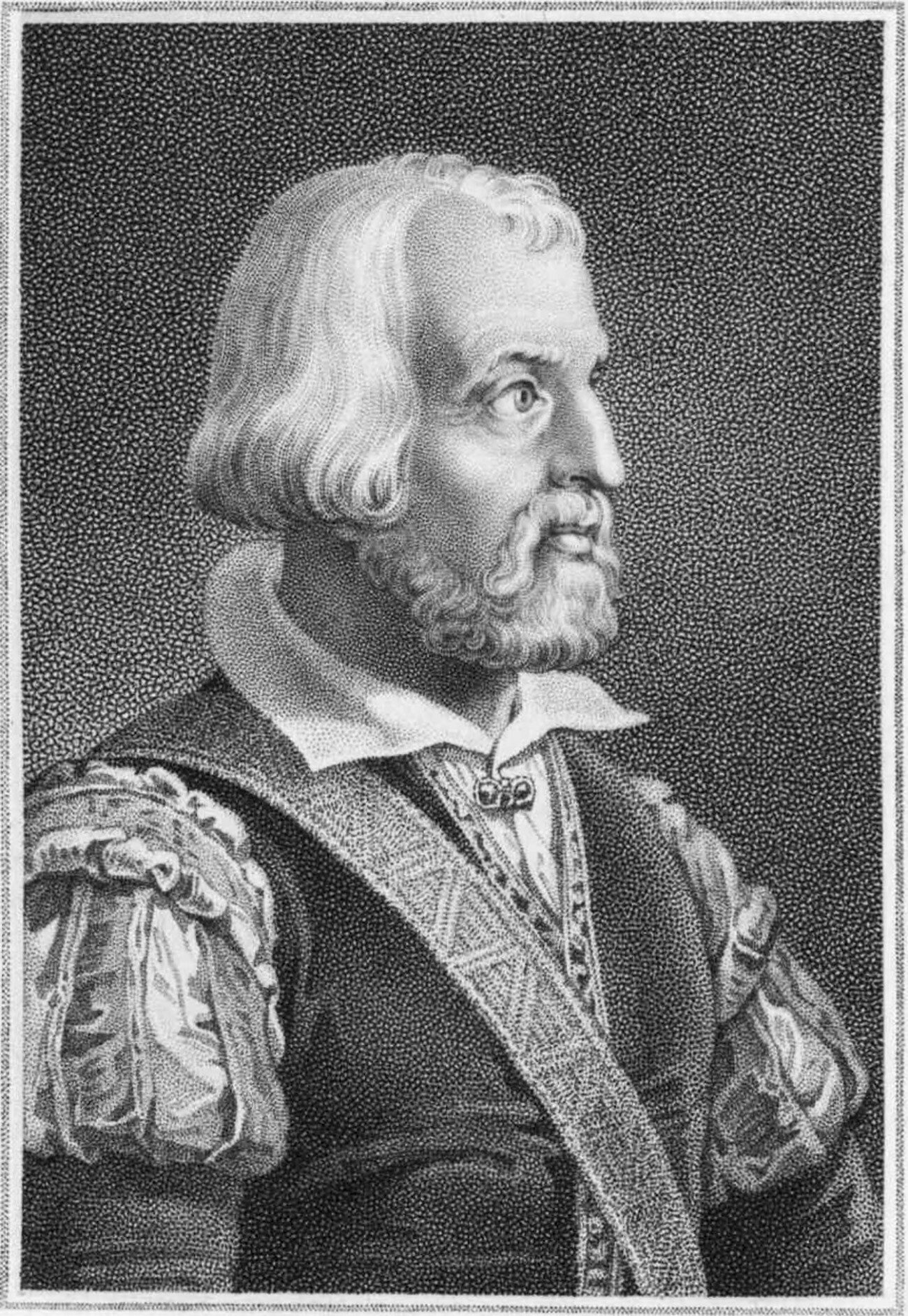

Sigismund von Herberstein

Public domain“When the ambassadors leave the palace, the very people who accompanied them to the palace take them back to their house, saying that they are instructed to be there and cheer the ambassadors. They bring silver bowls and vessels, each with a certain drink and they all try their best to make the ambassadors drunk.

They drink in this manner. The one who starts takes the cup and goes to the middle of the room, standing with his head uncovered, he eloquently states to whose health he drinks and what he wishes. Then, having drained and tipped the cup, he touches the top of his head with it to let everyone see that he has drunk and wishes for the health of the gentleman for whom he is drinking. Then, he orders the filling of several bowls and then gives everyone a bowl, calling the name of the one whose health is to be drunk. Everyone has to go one by one to the middle of the room and, having drained the bowl, return to their place. Those who wish to avoid the drink must pretend to be drunk or asleep, or at least assure them that they cannot drink any more, for they believe that to receive guests well and treat them decently is to get them drunk.”

A Russian chasha (bowl, about 1.1 litre)

Shakko (CC BY-SA 4.0)Both in the tsar’s palace and at feasts in ambassadorial courts, Russian courtiers, who were assigned to drink with the ambassadors, brought with them a long list of names of those people who they were supposed to toast, so that the reasons for drinking would not end. As Kluchevsky writes: “Courtiers often quite achieved their goal – to get the ambassador drunk and it did not go without sad stories. But, at the same time, sometimes other important goals were also achieved: the tipsy ambassador not once talked about what he was ordered to keep only on his mind.”

And what happened if the ambassador simply could not drink so much? In such cases, the Moscow tsar graciously allowed the foreign guest “not to finish it”, as happened with Ambrogio Contarini under Grand Prince Ivan III – the Italian could barely drink a quarter of the cup given him by the tsar, but Ivan Vasilievich himself allowed the ambassador not to finish the cup.

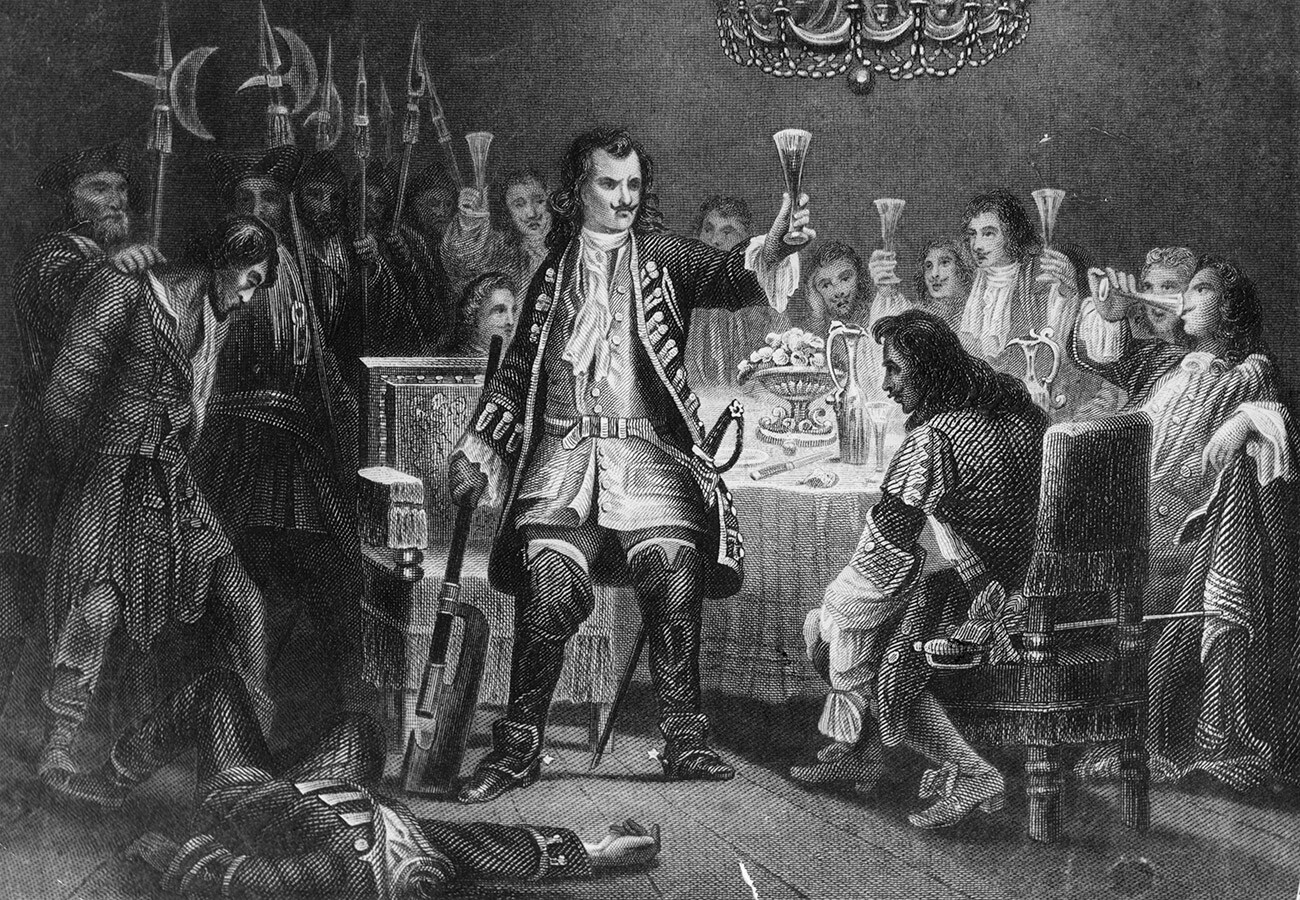

Peter the Great, raising a toast after beheading a Streltsy guard

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesBut the greatest enthusiast for getting foreign ambassadors and guests drunk was, of course, Peter the Great. European guests never drank as much as they did under him, neither before nor after. Friedrich Wilhelm Berchholz, a Holstein nobleman who knew Peter the Great personally and had to get drunk in his company, left the most evidence of this. “I was terribly afraid of drunkenness,” Berchholz confessed. Even his sovereign, Duke Karl-Friedrich of Holstein, understood this: “His Highness whispered to me that I should pour red water into the same wicker bottle as the Burgundy and mix it a little with wine.” This is how the Duke advised his subject to deal with Peter’s drunkenness.

Karl-Friedrich himself was not saved by such methods – Tsar Peter watched closely to ensure that his guests drank to his health “properly”. When the Duke of Holstein tried to drink diluted wine during the feast, Peter “took the glass from his highness and, having tasted it, returned it with the words: ‘Your wine is no good.’” When the Duke tried to object that he was not well and could not drink so much, the tsar said that diluted alcohol is even more harmful than pure, “and poured into his glass from his bottle of strong and bitter Hungarian, which he usually drinks”. When Peter found out that someone was not drinking enough, he became angry. As Berchholz recalls: “The tsar found out that at the table on the left side, where the ministers sat, not all the toasts were drunk with pure wine or at least not with the wines he demanded. His Majesty became very angry and ordered everyone at the table to drink a huge glass of Hungarian as a penalty. Since he ordered it to be poured from two different bottles and all who drank it immediately became terribly intoxicated, I think that vodka was poured into the wine.”

Charles Frederick, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp

Public domainIn short, Tsar Peter spared neither himself nor others in his passion for drunkenness. Fights and embarrassments were common at the tsar’s feasts. Berchholz wrote that “Admiral [Apraksin] was so drunk that he cried like a child, which is usual with him on such occasions. Prince Menshikov got so intoxicated that he dropped unconscious, and his men were forced to send for the princess and her sister, who with the help of various spirits brought him to his senses and asked the tsar’s permission to go home with him. In a word, there were very few people who were not completely drunk…”

It is known that Petrine drunkenness sometimes led to monstrous consequences – for example, the Duke of Courland Friedrich Wilhelm, whom Peter married to his niece Anna Ioannovna, did not survive a drinking party with the Russian tsar – two days after the wedding celebrations, the groom died on the road from St. Petersburg and contemporaries attributed the incident to the fact that the young Duke inconsiderately decided to compete with Peter in the art of drinking. Peter the Great, however, was the last of the Russian monarchs willing to drink so openly with his guests and subordinates. Under the later Romanovs, the formidable Russian tradition of alcoholic diplomacy had already run dry.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox