10:10 a.m., Chkalovsky airfield near Moscow. Two pilots are inside the cockpit of a MiG-15 UTI training fighter jet, including the planet’s first cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin. Their mood is a bit nervous: the flight is already delayed and everyone is waiting for the previous plane to finish its mission.

At 10:19, they finally take off. Gagarin is in contact with ground control. His voice now sounds calm and clear. After three minutes, he reports reaching the climbing limit and asks to elevate to 4,200 meters. Two minutes later, he talks about going over the upper edge of the clouds. However, in six minutes, Gagarin reports to ground control with the same calm tone of voice about completing the mission in the area and requests permission to turn around and land. This surprises the air traffic controllers, since only half of the fixed time to perform the mission has passed. At this point, communication with the pilots is cut off.

Yuri Gagarin (second from left) and cosmonaut Alexei Leonov (left) after their next flight on a MIG-15 in 1964.

Alexander Mokletsov/SputnikIt was 10:29 on the clock when their fighter jet entered a spin and crashed into the ground 65 km away from the airfield. The crash of March 27, 1968, went down in history primarily because of Gagarin’s death. The second victim - pilot-instructor Vladimir Seregin - is less often remembered. Although, it was his candidacy for a flight with Gagarin that the head of the Cosmonaut Training Center personally insisted on.

Vladimir Seregin was born into the family of a postal clerk and, after graduating from school at the age of 18, he joined the Red Army. They noted the young man’s talent and love for aviation, so they sent him to pilot school. Seregin graduated in 1943 and went to war as a military pilot.

Vladimir Seregin

SputnikThe pilot received his first award (the Order of the Red Star) at the beginning of 1944. The award documents mentioned the following feats. Behind the wheel of IL-2, he went on a mission: a bomber-attack raid on tanks in the region of Marievka village. German anti-aircraft guns were shooting at him from the ground, but Seryogin managed to aim and destroy two tanks. The next day - a similar situation happened. Evading fire, he successfully bombed three camouflaged railroad cars near Stalinodorf.

Once, he saved the life of a Soviet pilot who was being attacked by a German Fokke-Wolf. Seregin fired a long round, after which the Fokke-Wolf covered up with smoke and sharply descended into the ground. Seregin was wounded, but reached the airfield and landed on one landing gear.

Vladimir Seregin

SputnikAll in all, during the war, Seregin went on 140 combat and 50 reconnaissance flights. Such aces as he was were called ‘Stalin’s falcons’. In 1945, he became a Hero of the Soviet Union.

After the war, Seregin stayed in the aviation field and went to the Air Force Academy to supplement his extensive practice with theory. Then, after college, he tested new modifications of MiG-15 and Mig-17 fighters. “He performed test flights of any complexity, including flights with turned-off engines,” his personnel file reads.

In the mid-1960s, he was appointed commander of an aviation regiment and put in charge of cosmonaut flight training. The first cosmonauts in the USSR were fighter pilots (as these people were already familiar with g-loads, zero gravity, and were ready to navigate in conditions of noise, vibration, and high speed). Vladimir Seryogin had a colossal experience of flying in extreme conditions.

His colleagues liked to recollect a story of how once Seryogin flew on a supersonic fighter through a snowstorm and managed to land the plane almost blindly in near-zero visibility conditions. He also somehow managed to land an airplane that had ruined steering mechanisms. And he landed the fighter without a rudder.

The world's first female cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova and Vladimir Seregin

SputnikOn March 26, 1968, Nikolai Kamanin, Assistant Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Air Force for Space, was told that Yuri Gagarin was going to take a piloting techniques exam on a MiG-17. But, Kamanin decided that the first cosmonaut should firstly perform a training flight on his own on a MiG-15 UTI. General Nikolai Kuznetsov, the head of the Cosmonaut Training Center, volunteered to fly with Gagarin, but Kamanin insisted that it should be Seregin.

The reason why the famous Gagarin, who had already flown into space, had to take the exam again, was a three-month “no-flying” break, during which he was busy working on his thesis at the Academy.

“Such flights are included in the training program of all cosmonauts. Without them, it is difficult, as we say, to be in flying shape. They not only refine your professional skills, but also test the ability to work under conditions of overload and noise,” Kamanin wrote in his memoirs.

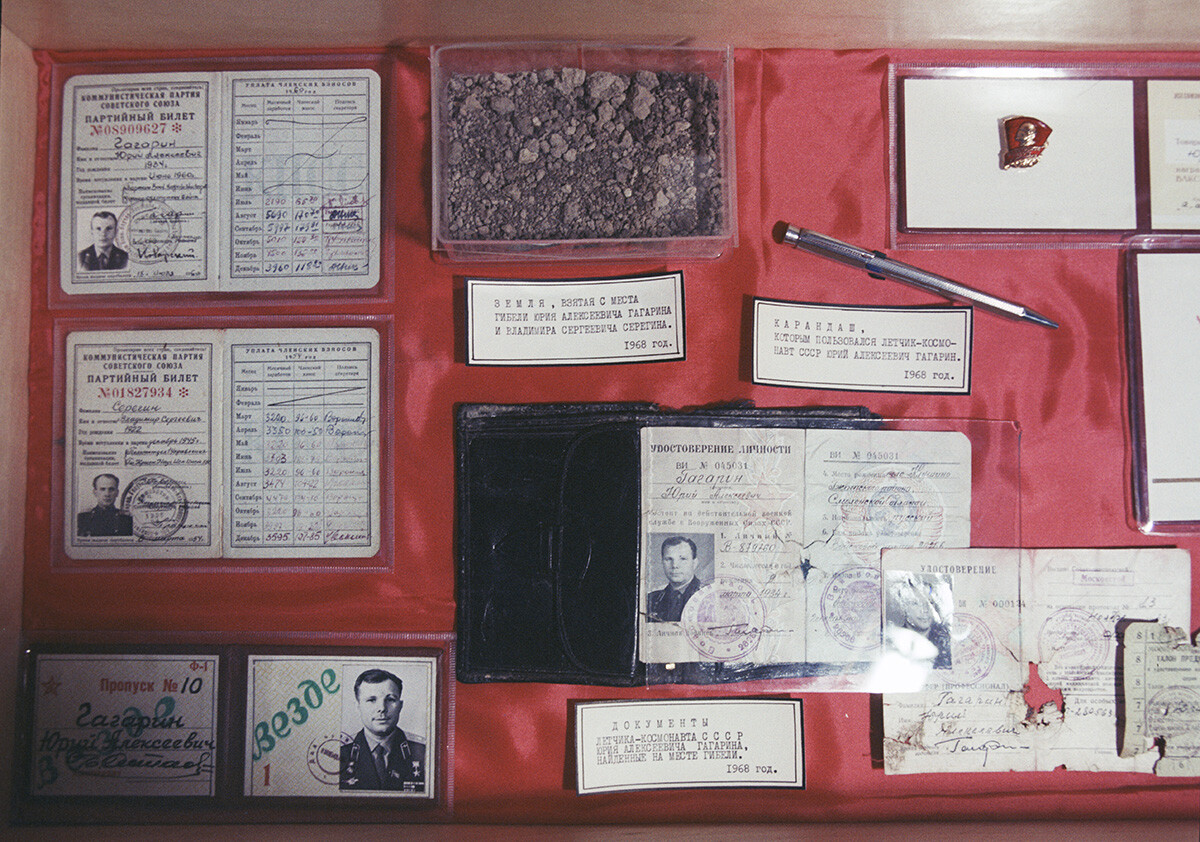

Documents of Yuri Gagarin and Vladimir Seregin, found at the scene of their deaths.

L. Nosov/SputnikFlying with such an experienced instructor as Seregin caused no doubts. Even after all communication was lost, everyone counted on a rapidly forced landing or, as a last resort, on the pilots’ ejection.

Residents of the city read a report in the Pravda newspaper about the tragic death of Yuri Gagarin and Vladimir Seryogin.

Valentin Mastyukov/TASSNevertheless, none of these scenarios happened. The plane was blown to pieces over a kilometer radius, and the pilots’ remains were not discovered until the next morning. The investigation resulted in 29 volumes classified as “secret” and even a brief conclusion about the circumstances of Gagarin’s and Seregin’s deaths was not published.

Memorial at the place of death

V. Kuzmin/SputnikOnly in 2011, based on declassified documents, the probable cause of the crash was named to be a sharp maneuver taken by one of the pilots (it is still unknown by whom exactly). Because of this, the plane went into a spin and collided with a balloon-probe. According to an alternative version, the plane of Gagarin and Seryogin flew dangerously close to another fighter jet and got caught in its vortex trail.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox