The Alchemist (1634). David Ryckaert III

Imagno/Getty Images“The fierce magus Bomelius”, as Russian sources dubbed this person, arrived in Moscow in 1570 from London, where he had been a physician and an astrologist; however, at the court of Ivan the Terrible, he gained the dubious fame of a poisoner.

Bomelius hailed from the Netherlands and studied at the University of Cambridge to acquire a degree of doctor of medicine, but couldn’t pass the last (sixth) year of his study. That, however, didn’t stop him from beginning his practice and, soon enough, he built himself quite the reputation – Sir William Cecil, the chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I, even consulted with him regarding the queen’s health. That, though, couldn’t save Bomelius from prison, when he was exposed for practicing medicine without a license. It turned out that the “doctor” had no funds to pay the fine, so he was forced to spend three years in prison. In 1570, when he managed to get released, he caught the attention of Andrei Sovin, the Russian ambassador to England, who was in search of a physician for Tsar Ivan. Subsequently, Bomelius began his service to the tsar.

“The spiteful slanderer Bomelius concocted deadly potions with such devilish skill that the victim he poisoned gasped their dying breath at the precise minute planned by the tyrant,” Nikolay Karamzin wrote, which pretty much sums up everything we know about Bomelius’ work in Moscow. As the tsar’s physician, he received tremendous amounts of money, which he partially sent back to his homeland, to a town called Wesel.

But Bomelius’ reputation was not destined to last long – in 1574, he was exposed for spying on Ivan the Terrible for Denmark and Sweden and subjected to gruesome torture: he was roasted alive on a spit and left to die in a dungeon. After this incident, for a long while, the tsar had trouble finding a new physician.

Portrait of Joseph Balsamo, comte de Cagliostro. Private Collection.

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty ImagesAn odious European charlatan, “Count” Cagliostro (his real name was Giuseppe Balsamo), arrived in Russia in 1779. By that time, he had already suffered several exposés and failures and, in Saint Petersburg, his affairs also went poorly, at first. Fascination with science had been in vogue, promoted by Empress Catherine herself, while mysticism and secret societies were treated by the Russian nobility with caution. Hence, Cagliostro had to put on the mask of a healer, since this was what the empress recommended him to do. “Since you, count, are versed in healing, put your efforts into this noble occupation, for alleviating people’s suffering is truly a wise man’s calling,” Catherine said during her only audience with Cagliostro.

Then, Cagliostro started his practice – accepting payment, however, only from the rich. Things got better with this new audience; the count healed his new friend, a renowned Russian Freemason Ivan Yelagin, from a migraine and Senator Stroganov – from a neurotic disorder. But, as soon as it came to patients with more serious illnesses, everything went awry. After attending Cagliostro’s sessions, a collegiate assessor named Islenev became a heavy drinker. After the count admitted the two-year-old Pavel, the son of Prince Gavriil Gagarin, for treatment and then returned him to his parents in perfect health, rumors began to spread that Cagliostro had simply replaced the child with an impostor.

Count Cagliostro spent nine months in Saint Petersburg; he left empty-handed, not finding the success he was hoping for. Empress Catherine the Great even wrote a comedy 'The Deceiver,' in which she mocked Cagliostro under the name ‘Kalifalkzherston’. It’s also quite possible that the empress hurried to expel Cagliostro, because his wife, Lorenza, had grown too close with Count Potemkin, one of the empress’ favorites.

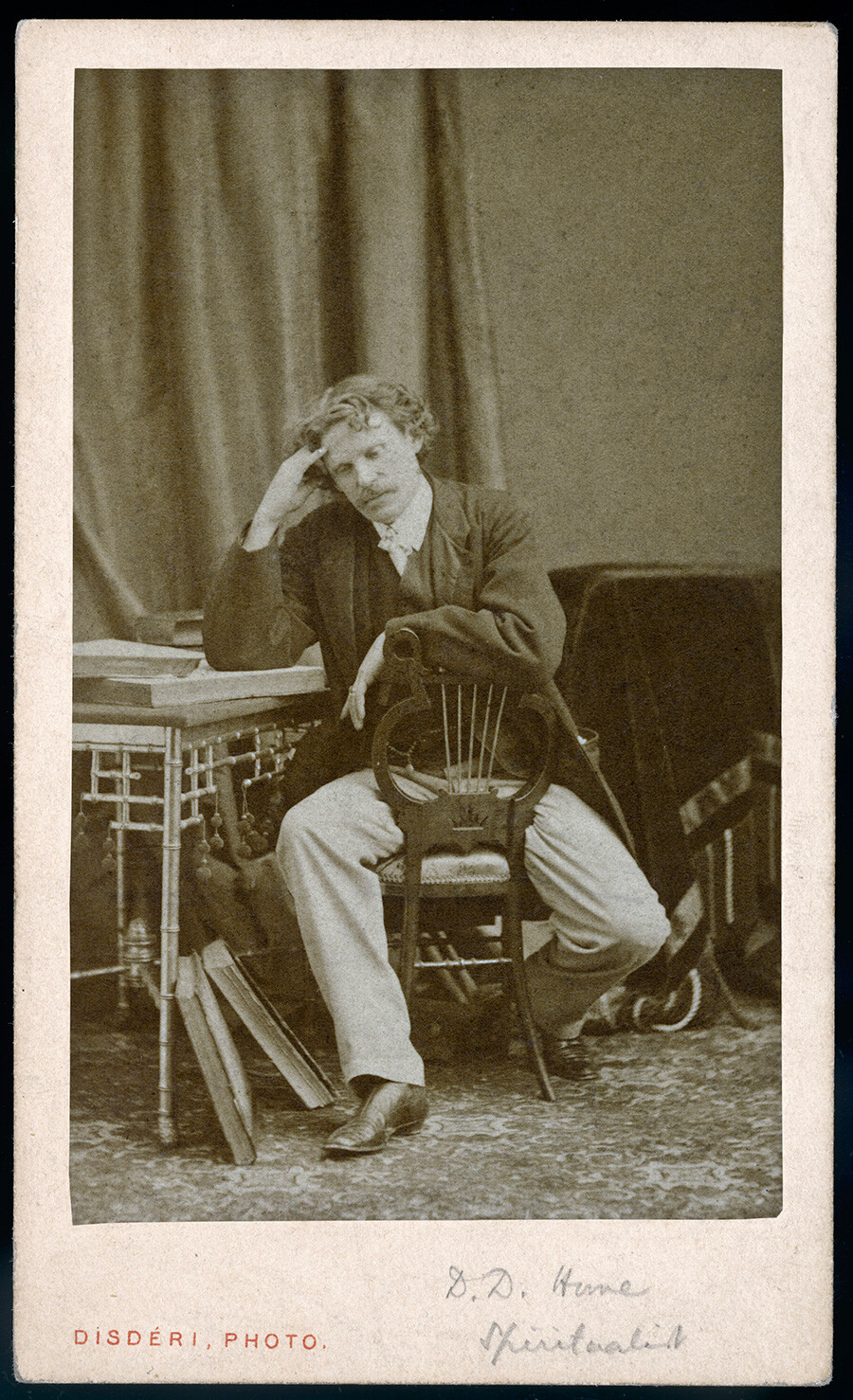

Daniel Dunglas Home, Scottish Spirit Medium, C.1860s

Legion MediaCagliostro’s bad reputation lingered in Russia for a while. “Man is strangely drawn to all things supernatural and he deceives himself remarkably easily in the most honest way – this explains the strong influence of Cagliostros of all times and it also promotes the great success of spirit boards,” Anna Tyutcheva, lady-in-waiting at the court of Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna, wrote in 1853, talking about the Grand Duchess’ husband's, Grand Duke Alexander Nikolayevich (the future emperor Alexander II), fascination with table-turning. “The fact is, the tables do indeed turn and spell out messages; some even argue that they answer questions posed to them mentally,” Tyutcheva claimed.

In 1858, Daniel Home, a 25-year-old Scottish medium who performed telekinesis sessions, arrived in Russia. Tyutcheva described those seances, performed in the presence of the imperial couple: “The table rose to a height of half a yard over the floor. The Dowager Empress felt how someone’s hand touched the frills of her dress, grasped at her arm and pulled off her wedding ring. Then the hand grabbed, shook and pinched everyone present but the Empress herself, whom this hand avoided systematically. It took a bell from the emperor’s hands, carried it through the air and passed it to the Duke of Württemberg. All of this caused cries of fright, fear and surprise.”

Home’s seances were always performed in darkness; the “faces” of deceased relatives that appeared before the people present were nothing but the bare heels of the illusionist, smeared with phosphorised oil. The hands that grasped the enthusiasts of mysticism under the table belonged to Home himself or to his assistants. Eleven people took part in his seance in July 1858. The next day, the seance was repeated at Strelna and another one was performed in November.

Besides seizing success at court, Home had a wife in Russia, 17-year-old Alexandria de Kroll, who died in 1862 from tuberculosis. In 1871, Home married a Russian woman again – Julie Gloumeline, a sister-in-law of the chemist Alexander Butlerov, who supported Home vigorously and helped him arrange his meetings with the tsar. For this marriage, Home even converted to Orthodox Christianity. However, when Butlerov attempted to prove that Home truly had psychic powers before an assembled scientific commission in St. Petersburg, the seance failed and the medium made a scene and retired to Europe, never to return again.

Nizier Anthelme Philippe

Legion MediaOut of all Russian imperial families, Nicholas II and his family were the greatest aficionados of the occult. Before Tsarevich Alexei (1904-1918) was born, Nicholas and Alexandra had been preoccupied with producing an heir – four daughters had been born to their family one after another. The tsar and his wife went on pilgrimages and sought the company of mediums and clairvoyants.

In 1900, Nicholas II discovered Nizier Anthelme Philippe, who had gained the reputation of a healer and an occultist in France. The emperor met the miracle worker during his visit to France and invited Philippe to St. Petersburg. Nothing could change the emperor’s mind – not even a report on Nizier Anthelme, put together by Pyotr Rachkovsky, the chief of the Russian secret service in Paris, that proved that the psychic was no more than a regular charlatan. After this report, Rachkovsky was taken off duty, while the “maestro” Philippe was welcomed at court, where he began to perform “seances” with the empress.

“This is a man of small stature, black-haired and with a black mustache, about 50 years old and quite unsightly, with a foul southern French accent,” Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich wrote about him. The maestro’s medical education was limited to just three years of medical school at the University of Lyon, after which he began his practice as a psychic, mostly treating wealthy women.

“He claimed that he possessed the power of suggestion that could influence the sex of the child developing in a mother’s womb. He didn’t prescribe any medication that could be checked by the court physicians. The secret to his art lay in hypnosis sessions. After two months of treatment, he announced that the empress was expecting a child,” Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich wrote.

Nizier Anthelme Philippe

Legion MediaThe fifth pregnancy of the empress began in November 1901. By spring, everyone noticed that Alexandra Feodorovna had become plumper and had stopped wearing corsets; however, she did not allow physicians to examine her – as maestro Philippe suggested, who she visited almost every day. When, in 1902, the empress was finally examined by the court obstetrician, Dmitry Ott, it turned out that she was not pregnant at all. The entire imperial family was in shock. However, this incident hadn’t changed the empress’ opinion of Philippe. His last recommendation to her, before he departed to France, was to seek the help of Seraphim of Sarov, a Russian Orthodox ascetic.

Seraphim of Sarov was then glorified by the Russian Orthodox Church the year after by the emperor’s order and the imperial family made a pilgrimage to the Sarov Hermitage. In 1904, their heir was born and the imperial family was convinced that it happened as per the prediction of maestro Philippe. As Anna Vyrubova, a Russian Empire lady-in-waiting, recalled: “Their Majesties at all times had a cardboard frame with dried flowers in their bedroom, gifted by Philippe, which, according to him, had been touched by the hand of the Savior himself.”

Of course, maestro Philippe was not the only charlatan who dwelled at the throne of the last tsar. Nicholas’ and Alexandra’s fascination with the blessed, the holy fools and the other “bearers of secret knowledge” was widely known among the masses. Of course, the most famous of them all was Grigori Rasputin. Out of all mystics at the court of the tsar, there is documentary evidence only about Rasputin's success in healing Tsarevich Alexei, stopping his bleeding with hypnosis. The hatred for Rasputin in Russian society was too strong – not least due to the shaky reputation of the imperial family, which was particularly fond of mysticism. Rasputin, in the eyes of the people, was the root of all the misfortunes that had plagued Russia. In the end, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, the first cousin of the tsar, personally participated in the assassination of the ‘elder’. But, by that time, the Empire was beyond saving.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox