Why did Russia help the United States during the Civil War?

"Our squadron was received here in a friendly manner, even to the extreme. It is impossible to show your face ashore in military dress… They will come up (even the ladies) to express their respect for the Russians and their pleasure at being in New York," wrote home Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, a famous composer in the future, and in 1863, a crew member on the Russian clipper Almaz, which was anchored in New York.

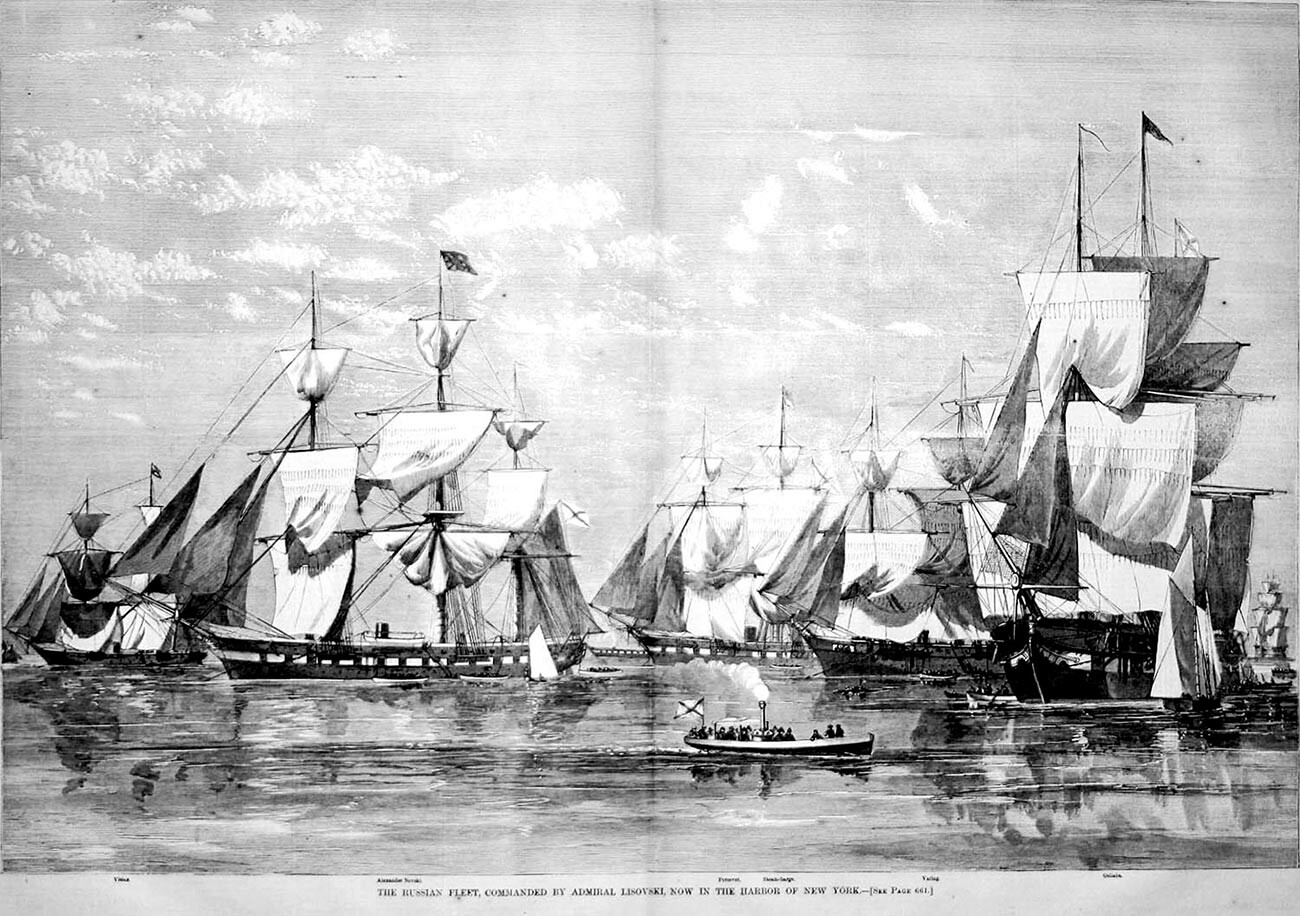

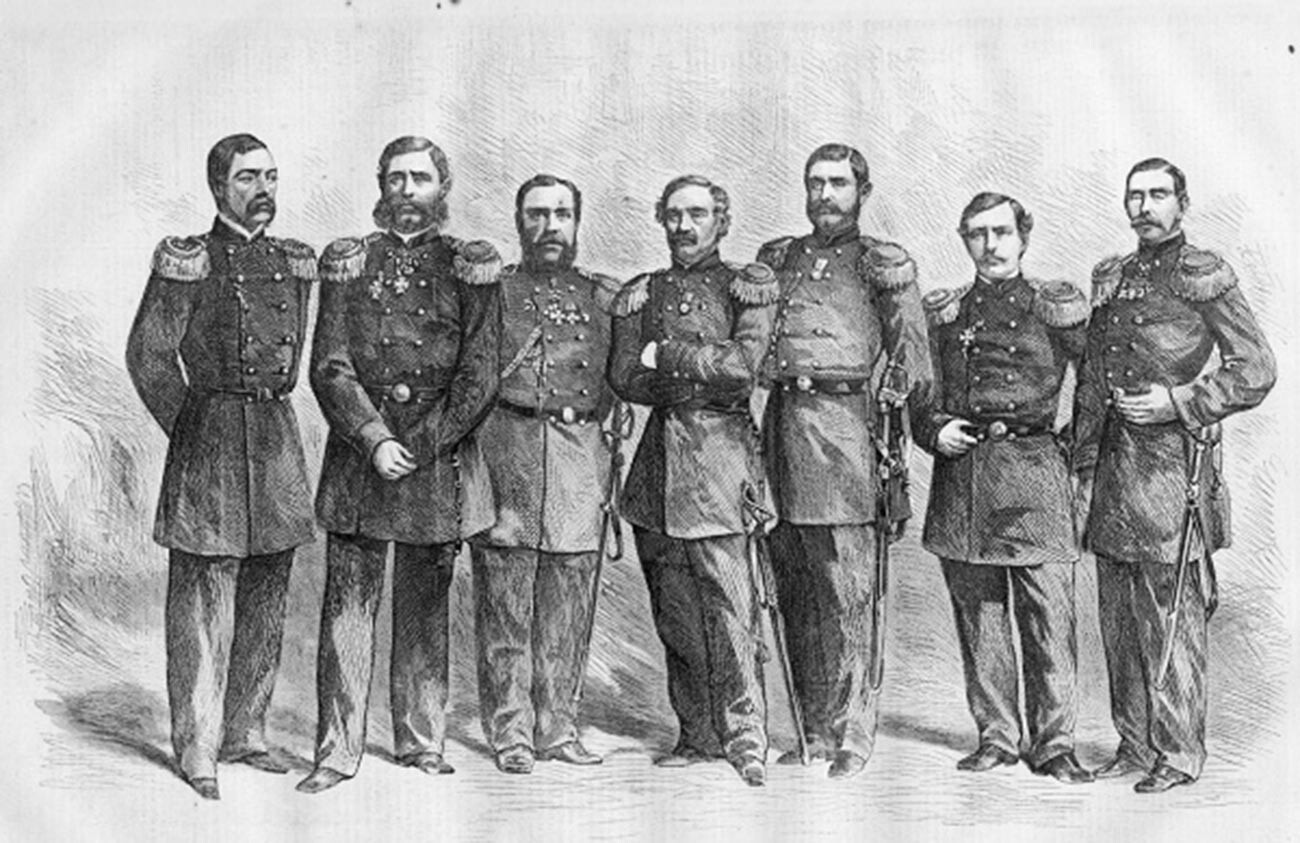

The mission of two Russian naval squadrons was so secret that the warships near the American shore came as a surprise even to Eduard de Stoeckl, the Russian Empire's ambassador to the Union. New York’s entire society was puzzled. The squadron commander, Rear Admiral Stepan Lessovsky, in a conversation with Thurlow Weed, said that the Russian government had provided him with sealed envelopes, which were to be opened only if the Union entered into an armed conflict with foreign powers. Lessovsky's squadron (six ships and 3,000 men) was not the only one – about the same time, in September 1863, Rear Admiral Popov’s squadron (six ships and 1,200 officers and sailors) berthed in San Francisco. What were the Russians up to?

How Russia and the United States became allies

Russian ships in New York Harbor

Russian ships in New York Harbor

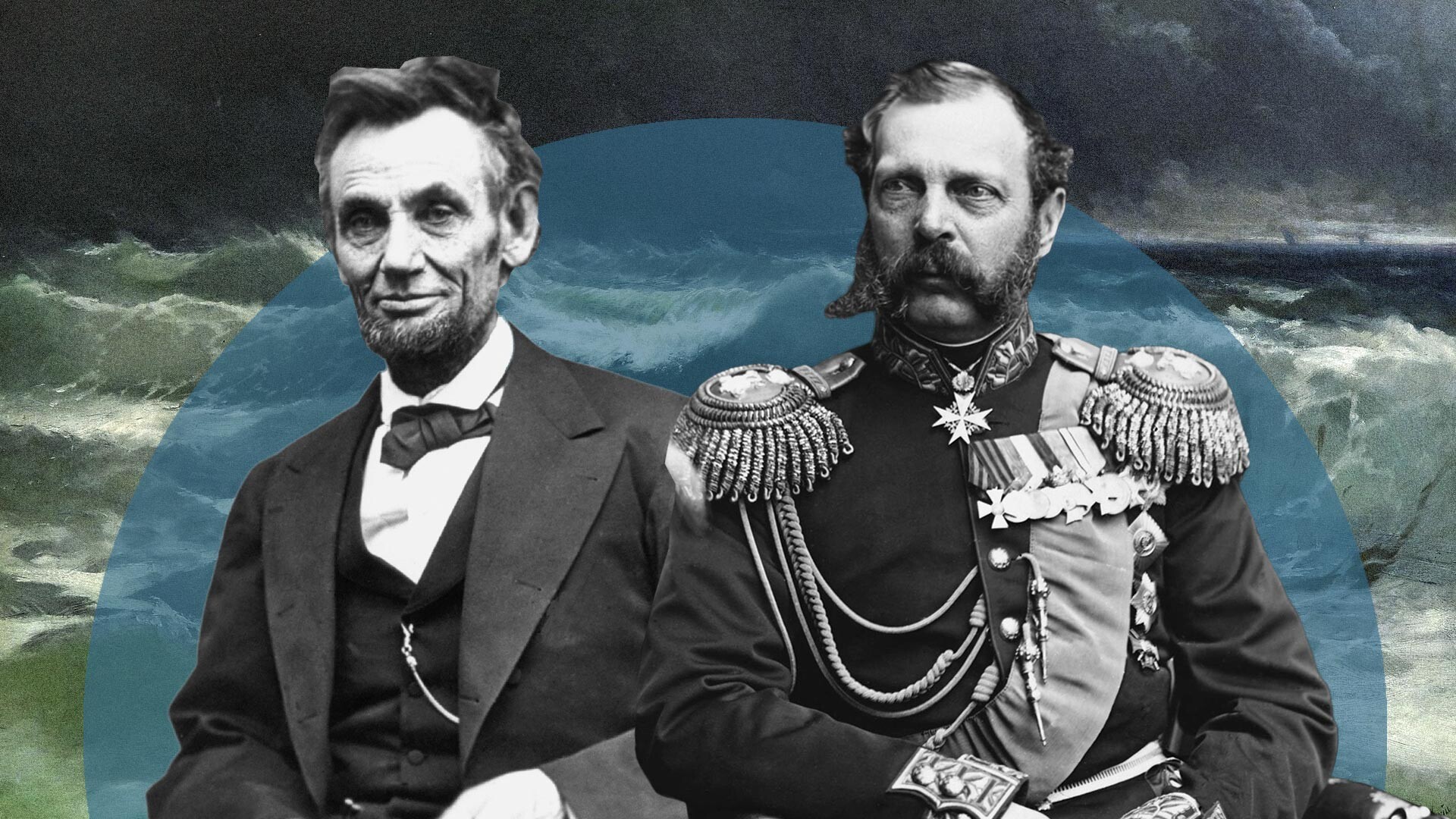

The Russian Empire originally supported U.S. independence from Britain. In 1776, after the outbreak of the War of American Independence, Catherine II refused King George III's request to send 20,000 soldiers to the American continent to defend the British Crown's possessions against revolutionaries. Russia continued to act against British interests in the next century as well.

Alexander II took the throne and began all-encompassing reforms in Russia after a bitter defeat in the Crimean War (1853-1856) against a coalition of Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire. The United States of North America remained neutral and even supported Russia – for example, American ships supplied Petropavlovsk with food and water during the British and French blockade of Russia’s Far Eastern coast.

In 1856, Russian foreign minister Prince Alexander Gorchakov wrote: "The sympathy of the American nation for us has not weakened throughout the war, and America has provided us directly or indirectly more services than could be expected from a power that maintains strict neutrality.” In addition, Gorchakov pointed out that "Russia's policy toward the United States is definite and will not change depending on the course of any other state. Above all we wish to preserve the American Union as an undivided nation... Russia has been offered to participate in plans for an intervention. Russia will reject any such proposals.”

Prince Alexander Gorchakov, Foreign Minister and later Chancellor of the Russian Empire

Prince Alexander Gorchakov, Foreign Minister and later Chancellor of the Russian Empire

Defeat in the Crimean War greatly weakened Russia and lowered its international prestige. When in 1863, Poland (part of Russia since 1815 as the Kingdom of Poland) revolted against Russian rule, Britain and France decided it was time to put more pressure on St. Petersburg. Russia, which sent troops into Poland to suppress the revolt, was accused of enslaving the Polish people. Britain’s House of Commons began to issue statements about the loss by Russia of all rights to the Kingdom of Poland, and in June 1863 Britain and France demanded the convening of a congress of European powers to resolve the Polish question. But, as The New York Daily Tribune observed, "No sincere sympathy for the sufferings of the Poles can be expected from the English, French, and still less from the Austrian governments.”

At the same time, London and Paris tried to intervene in the American Civil War. Recognizing the Confederates as a belligerent side in the conflict, Britain was ready to support them in action – the control of the South and its cotton, produced with slave labor, was essential to the British textile industry. In June 1863, England sent five warships to the port of Esquimalt in British Columbia, Canada. The North American states, meanwhile, had no navy of their own.

France, for its part, had designs on Mexico – in June 1863, the French army captured Mexico City. In addition, the French secretly supplied the Confederate troops with arms. Under such circumstances, on June 25, 1863, Alexander II sent his warships under the command of two Rear Admirals to the U.S. coast in strict secrecy.

How the Russian navy helped protect the United States

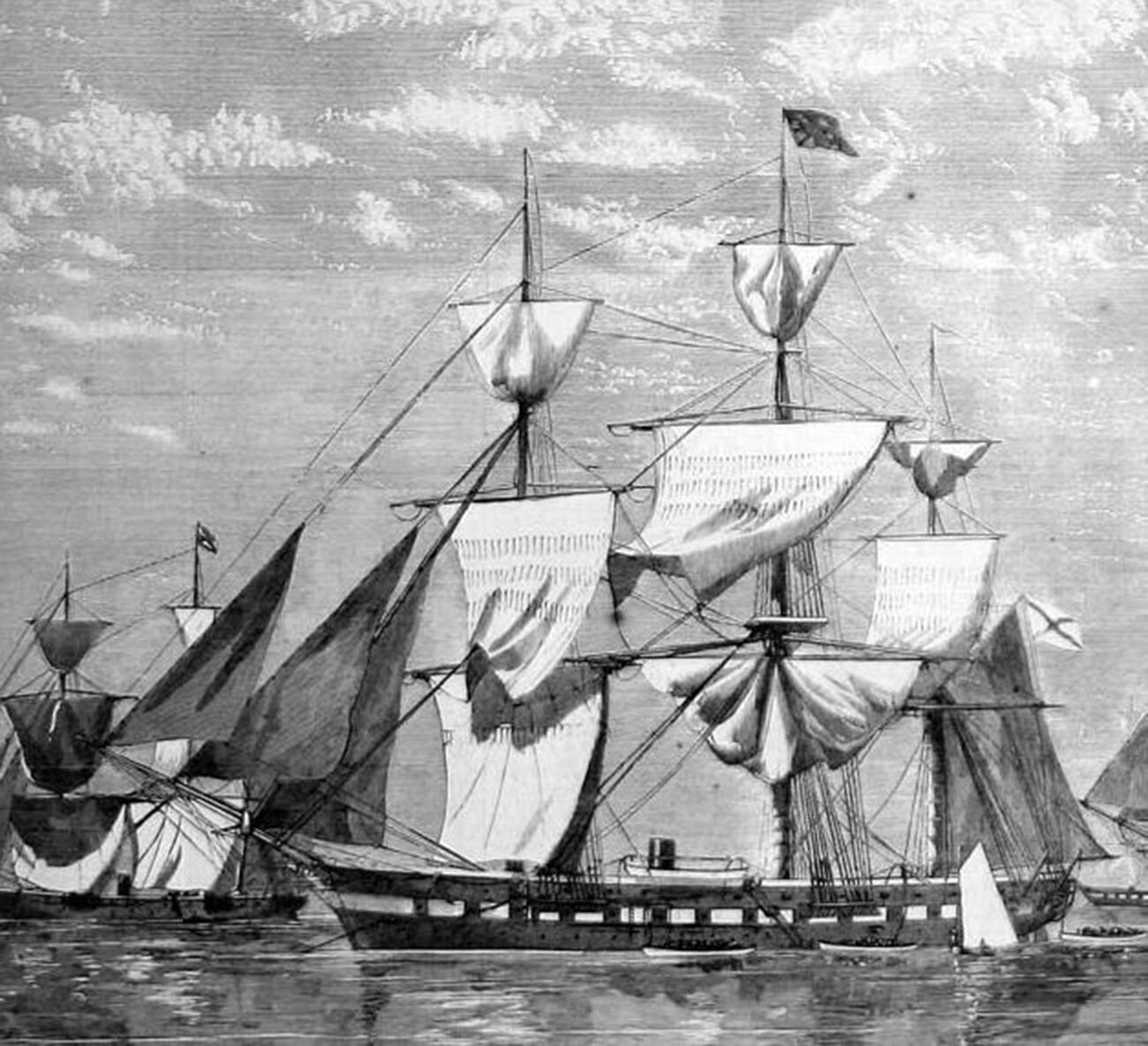

Frigate "Alexander Nevsky"

Frigate "Alexander Nevsky"

"Although the Russian fleet came for its own reasons, the advantage of its presence was to convince England and France that it had appeared to protect the United States from interference," wrote U.S. Secretary of State William Seward. Eventually, the Russian fleet left American shores without even once encountering any enemy ships. Nevertheless, in the event of such an encounter, the Russians would know what to do – “prepare for battle”, as Rear Admiral Popov’s order to his vessels in the Frisco port read. However, the two Confederate frigates stationed in the Pacific – the Alabama and the Sumter – never dared to threaten Russia’s warships.

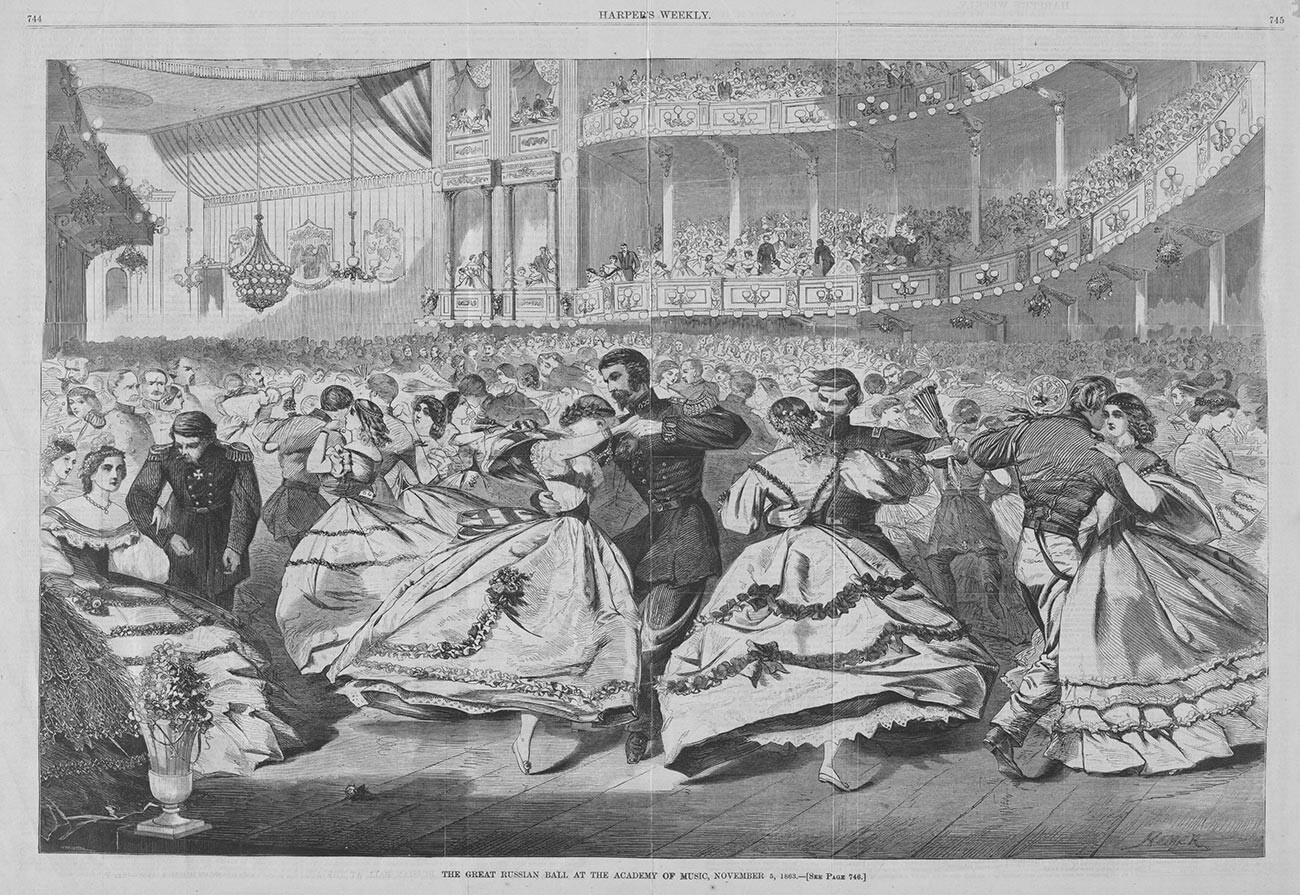

The Russian squadrons’ stay lasted from September 1863 to July 1864. During this time, the Russians visited Cuba, Honolulu, Jamaica, Hawaii, and Alaska, and of course, managed to be the stars of balls and receptions. As the American researcher Marshall B. Davidson wrote, "The ships’ officers were swept at once into a whirl of official ceremonies and social celebrations that must have tried their stamina beyond anything they were likely to encounter on the open sea.”

The November 5, 1863, Russian ball in New York

The November 5, 1863, Russian ball in New York

The most memorable occasion was the November 5, 1863 ball in New York City. The New York World reported that the banquet served 12,000 oysters, 1,850 turkeys, chickens, and pheasants, and opened 3,500 bottles of wine. The tables were decorated with sugar sculptures of the current rulers of the two states – Abraham Lincoln and Alexander II – and their founding fathers, Peter the Great and George Washington. The ball thrown for the Russians far exceeded the scope and expense of the official reception the Americans gave the Prince of Wales the year before. The Russians soon hosted a return ball in their own territory, aboard the flagship frigate Alexander Nevsky. The dancing lasted 11 hours, and at the end of the banquet,Rear Admiral Lessovsky donated $4,700 to the poor of New York. Of course, there was also an official reception with Lessovsky and the squadron command staff invited to the White House to meet Abraham Lincoln.

Why did the Russian Empire send a fleet to America's shores?

The captains of the expedition, L to R: Pavel Zelenoy, Ivan Butakov, Mikhail Fedorovsky, Rear Admiral Stepan Lessovsky (squadron commander), Nikolay Kopytov, Oscar Kremer, Robert Lund.

The captains of the expedition, L to R: Pavel Zelenoy, Ivan Butakov, Mikhail Fedorovsky, Rear Admiral Stepan Lessovsky (squadron commander), Nikolay Kopytov, Oscar Kremer, Robert Lund.

During the time the Russian squadrons were near American shores, neither France nor England dared to attack the Union – or Russia in the Polish territories, for that matter. In June 1864 the Polish uprising was suppressed and the Russians were ordered to return home. This was no coincidence.

Both Russian squadrons were too weak to put up any significant resistance to the combined naval strength of Britain and France. However, they could seriously disrupt their overseas commerce. “In case of war,” the Naval MInister of Russia’s instruction to Lessovsky read, “destroy the enemy's commerce and attack his weakly defended possessions. Although you are primarily expected to operate in the Atlantic, you are at liberty to shift your activities to another part of the globe and divide your forces as you think best.”

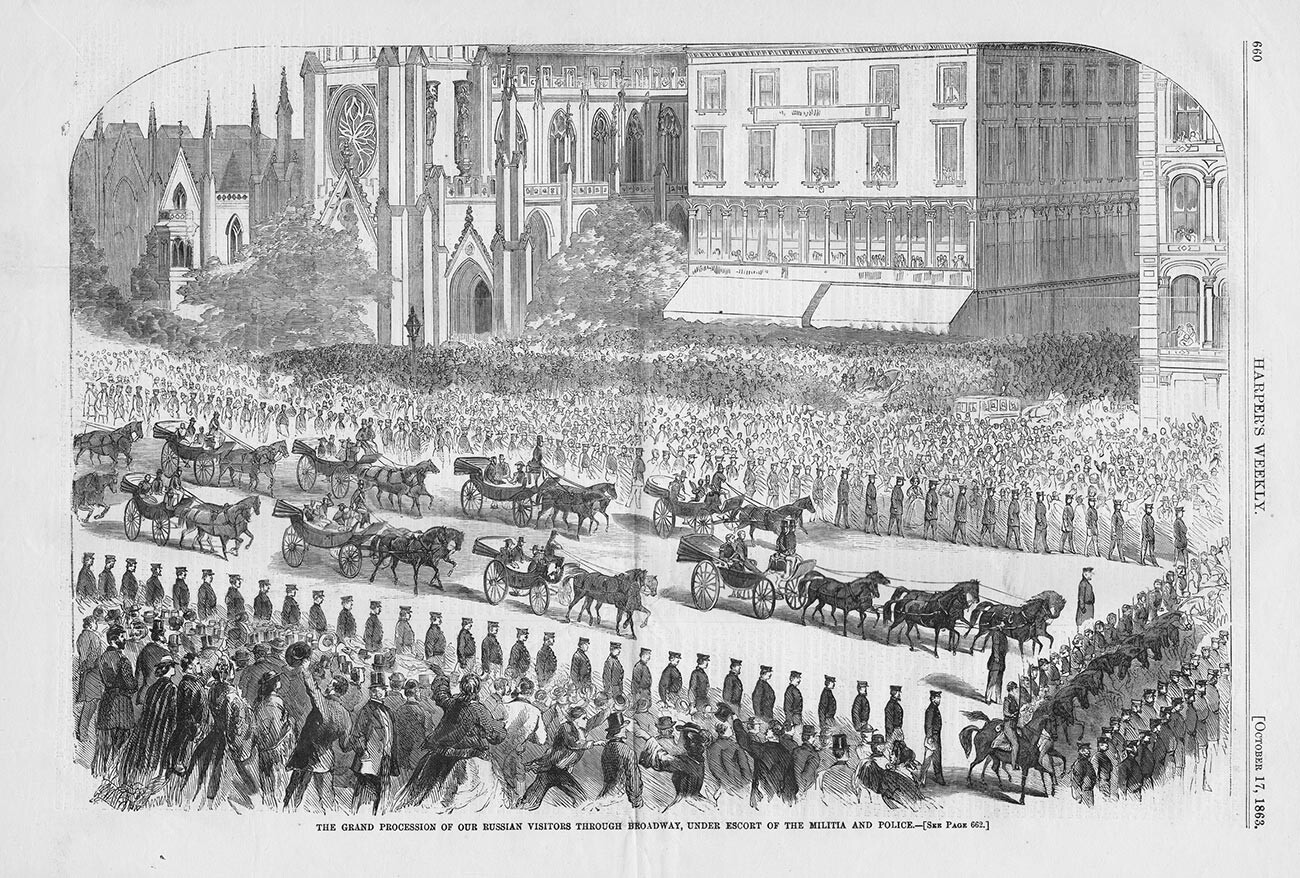

Russians marching on Broadway

Russians marching on Broadway

Lessovsky and Popov were specifically instructed not to enter the conflict between the Union and the Confederation. Their positioning in the American ports ensured that if Great Britain would start an open war against Russia, at least these two squadrons would be at hand to attack British and French naval trade. As Russian naval minister Nikolay Krabbe put it, “a few Russian guns in the ocean would have more influence on England than a much larger number in Sevastopol [did].” Indeed, Lessovsky and Popov’s mission was successful without a single shot fired. Alexander II looked at the operation as one of the greatest practical achievements of the Russian Navy, and a significant page in the history of his own reign.

Rear Admiral Stepan Lessovsky

Rear Admiral Stepan Lessovsky

At a reception held at the American Embassy in St. Petersburg for the sailors of the two squadrons after their return to the capital, Henry Bergh, secretary of the embassy, said: "A friendship exists between us, unmarred by any bad memories. It will continue as long as we adhere to the firm rule of not interfering in each other's internal affairs. It is not difficult to imagine the tremendous advantages that such a policy can confer on all the governments of the globe if they adhere carefully to it in their international relations.”