“Suddenly, from the darkness we moved to a street with bright lighting. In two streetlights, kerosene lamps were swapped for incandescent light bulbs, emanating bright white light. The assembled people, with awe and surprise, admired this fire from the sky, the ‘light with no fire’, as it was immediately dubbed by the inhabitants of St. Petersburg,” a contemporary described the first public test of light bulbs in Russia.

In 1873, Russian scientist Alexander Lodygin lit the streetlights on Odesskaya Street in St. Petersburg to ensure that his invention worked properly. Back then, no one could fathom that this event would herald a new stage in the development of the illumination of the country.

The house on Odesskaya str. in St. Petersburg, where Lodygin lit the first electric street light.

Google mapsAfter such an impressive demonstration, Lodygin’s name became known around the world. Riding the wave of his success, he founded the ‘Electric Lighting Company, A.N. Lodygin and Co.’ company. His team set ambitious goals: to illuminate specific districts first and all of St. Petersburg next. But, local businessmen, engaged in the industries of gas- and oil lighting, didn’t want to give up their lucrative businesses.

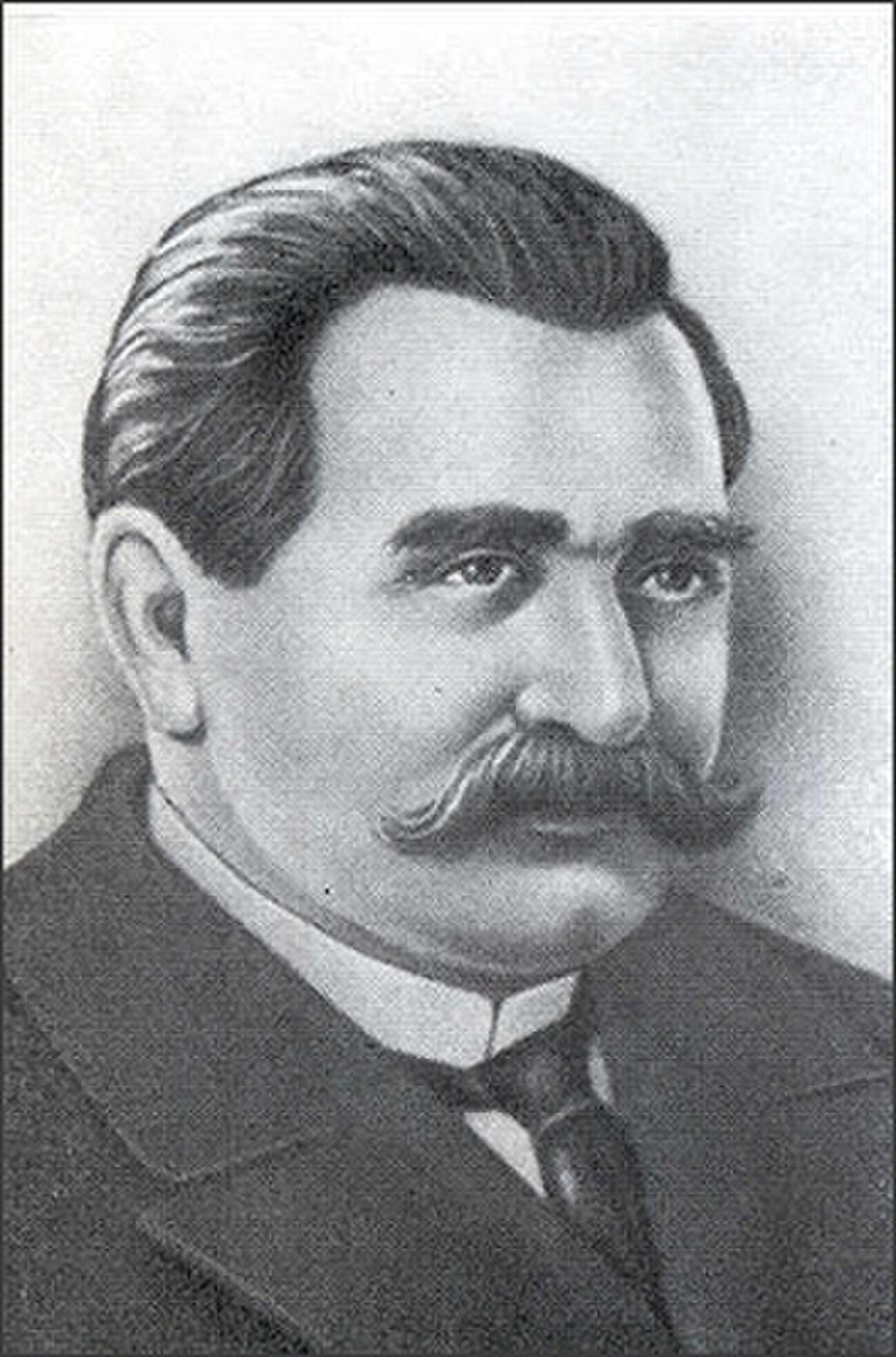

Alexander Nikolayevich Lodygin (1847-1923)

Public domainBesides, Alexander Lodygin was unpopular among the authorities: it was known that he sympathized with the revolutionaries.

At the same time, another Russian scientist named Pavel Yablochkov was working on lighting devices. He designed an electric candle that offered greater illumination compared to Lodygin’s light bulb. To really make a statement, Yablochkov’s company had to put on a show on a larger scale than what Lodygin had already done.

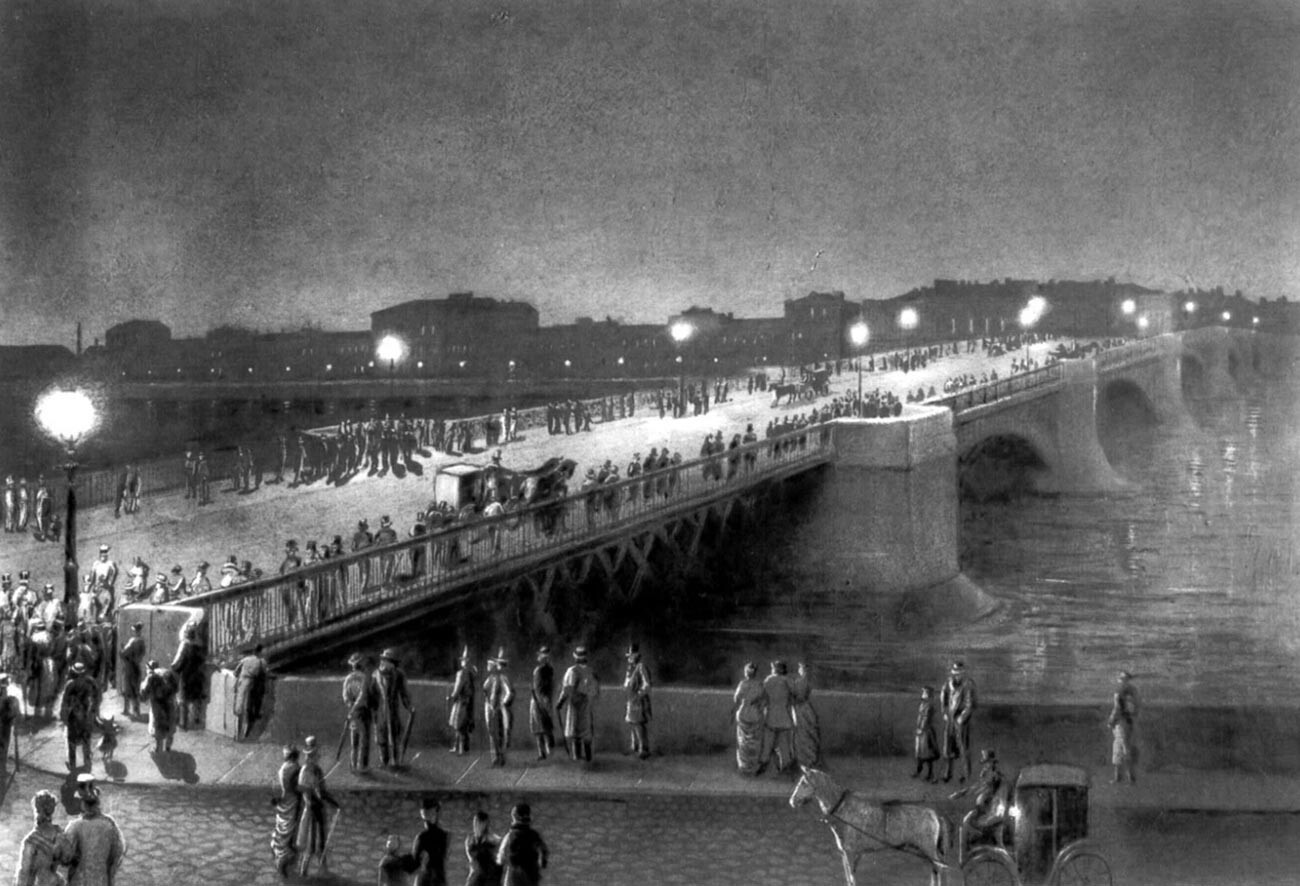

The Liteynyi bridge illuminated

Public domainHe got his chance in 1879: the Liteyny Bridge was opened in St. Petersburg and the local “gas lighters” weren’t given permission to illuminate it – it went to Yablochkov instead. Despite the success of this illumination, Yablochkov couldn’t, in the end, earn anything off his invention in Russia – his company quickly went bust. However, electrical lighting did, after all, enter the life of St. Petersburg. “At night, the streetlights came to life without the help of a lamplighter, all at once along the entire Nevsky Prospekt and Bolshaya Morskaya Street; first, something crackled and slightly flickered within them. Then these milky-white eggs turned a touch purple and a pensive, as if suggestive, bee-like buzzing poured down on the passers-by along with this vaguely purple, trembling light,” this is how author Lev Uspensky remembered the first electric streetlights.

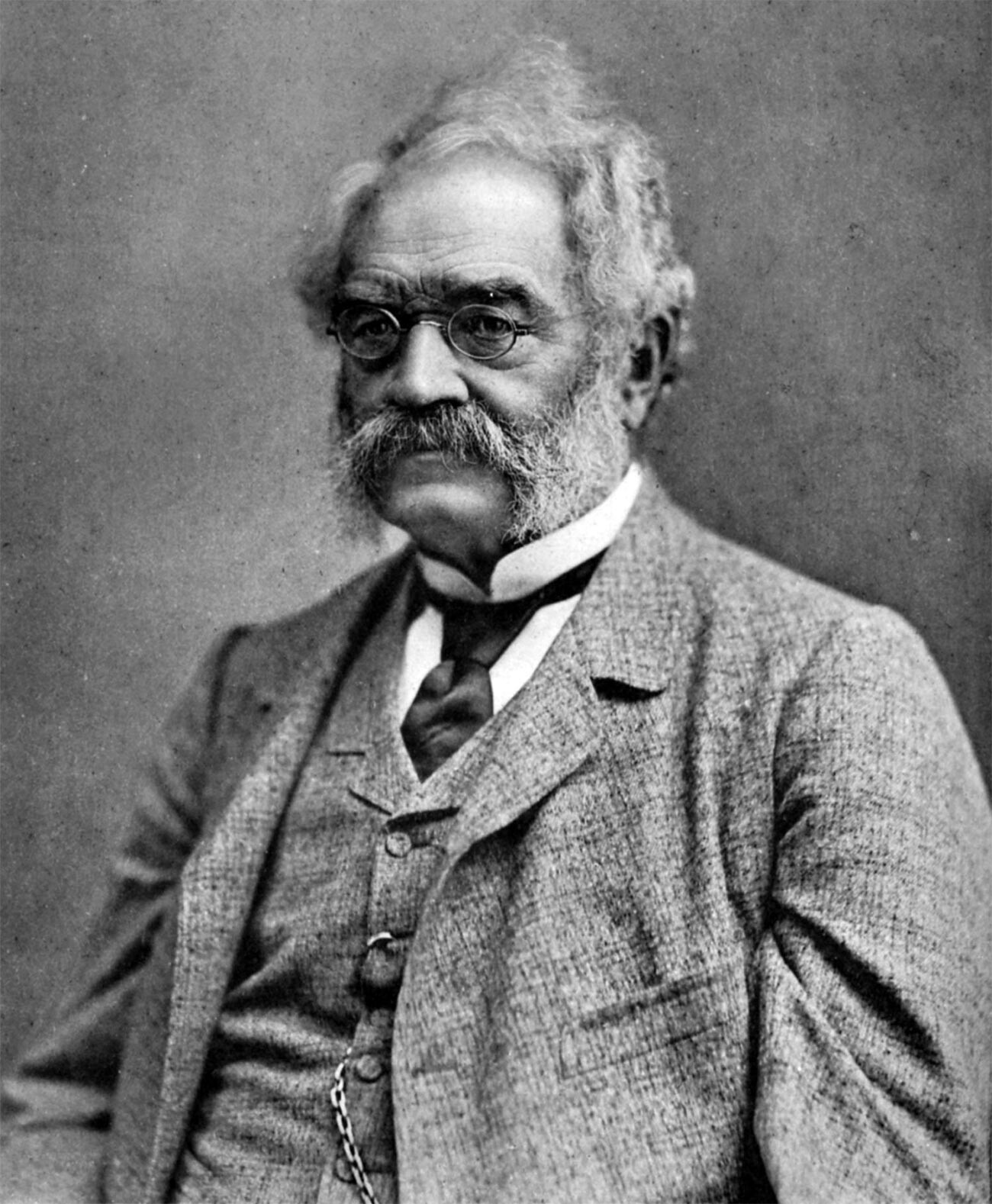

Ernst Werner von Siemens

Public domainIn the 19th century, Russia was more and more often visited by foreign businessmen, who saw a new market in the giant country. Ernst Werner von Siemens, a German engineer, received an order from the Russian government to establish telegraph lines to connect Russia and Europe. After founding a Russian subsidiary company called ‘Siemens & Halske’ with his brothers, he got to work. Werner decided to develop his business in Russia without the use of imported components, due to the high customs duties.

In 1882, ‘Siemens & Halske’ presented the samples of their products at the All-Russia Art and Industrial Exhibition in Moscow. A miniature electrical railroad with a little train ran along the exhibition pavilions; the emperor and his family took several rides on this train. Alexander III was so happy that all the exhibited products were made in Russia that he immediately awarded Siemens’ company the title ‘Supplier of The Court of His Majesty’ and granted it the right to use the double-headed eagle as its trademark.

The Kremlin illuminated by Siemens in 1883, during the coronation ceremony for Alexander III

Konstantin MakovskySeveral months later, Alexander III offered the Siemens brothers’ company to organize an electrical illumination on the day of his coronation that was scheduled on May 15, 1883. A mobile power station was especially built for the occasion that was able to supply both the Moscow Kremlin and the Ivan the Great Bell Tower with electricity. And the coronation was a great success! The official report stated: “The people stood silently along the embankment; many sat on the steps leading down to the Moskva River and, as if enchanted, watched this heavenly display in silence… Like rubies, emeralds and diamonds, the lights flared up on the tall towers; the entire side of the embankment, opposite to the kremlin, turned into a long chain of golden garlands; twelve tall fountains, shooting from the very pavement, shone with rainbow lights. Plaques all around sparked up with luxurious monograms, shields and inscriptions. The kremlin – this mighty, noble bogatyr [a hero or a mighty knight], awaited its turn. Millions of lights appeared on its golden domes and solemnly attested to the greatness and the sanctity of the day passed…”

In 1886, Siemens brothers founded the ‘Electrical Illumination Society’ – a company that soon became the leading electrical illumination company in Russia. However, for a long while, conservative Russian society couldn’t admit that a new era of illumination was dawning. Many fought back against mass electrification, appealing to its high cost. And yet, Moscow merchants struck gold in electrical lighting, using light bulbs on the displays of their stores and in their advertising signs. Indeed, that stirred excitement among the masses and many visited these trading houses with delight. Some cultural establishments also paid close attention to electricity. The Russian Drama Korsh Theater, introducing electrical lights in its performances, achieved the unthinkable — the loyal visitors of the Bolshoi Theater began to visit the Korsh Theater’s performances more often – to admire their electrical novelties.

The Georgievskaya power station in Moscow

Public domainTwo years after the founding of the ‘Electrical Illumination Society’, the first power station in Moscow was opened – the ‘Georgievskaya’ power station. Its capacity, by modern standards, was quite low – only 10 kW (the capacity of the oldest power station in Moscow, ‘1st State Power Station named after P.G. Smidovich’, as of the present day, is 86 MW). But, for the Russian Empire at the end of the 19th century, it was a true breakthrough.

Moscow illuminated during Nicholas II's coronation ceremony by Albert Benois

Albert BenoisThe imperial family, meanwhile, watched the work of the Siemens brothers’ company closely. Future Emperor Nicholas II clearly understood who would be in charge of illumination during his coronation and didn’t doubt his choice even for a second. A significant event for the Russian Empire happened in 1896. Russian society had never seen such a bright coronation before. In an instant, the kremlin lit up with thousands of lamps; it seemed that the entire country could see this light.

As General Vladimir Dzhunkovsky remembered, “…the Kremlin's illumination lit up in an instant – the very instant when Her Majesty accepted a bouquet of electrical flowers. The bouquet came alight and, at the same time, the entire kremlin became dressed in colorful electrical lights, as if drawn by a fire brush against the darkened sky…”

Quite a rapid start of electrification in the country heralded the widespread use of electricity in the near future. But, the Russian Empire was not at all ready for such innovations. The country had no large power stations that could create a centralized power system. ‘Electrical Illumination Society’ members began their work planning the construction of thermal and hydroelectric power plants across Russia.

Counting only hydroelectric power plants, by 1914, Russia had around 80 operating power stations. However, World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution at the beginning of the 20th century forced Siemens company to leave Russia. Electrification, naturally, remained a pressing problem for the country – but now, the new Bolshevik authorities had to solve it.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox