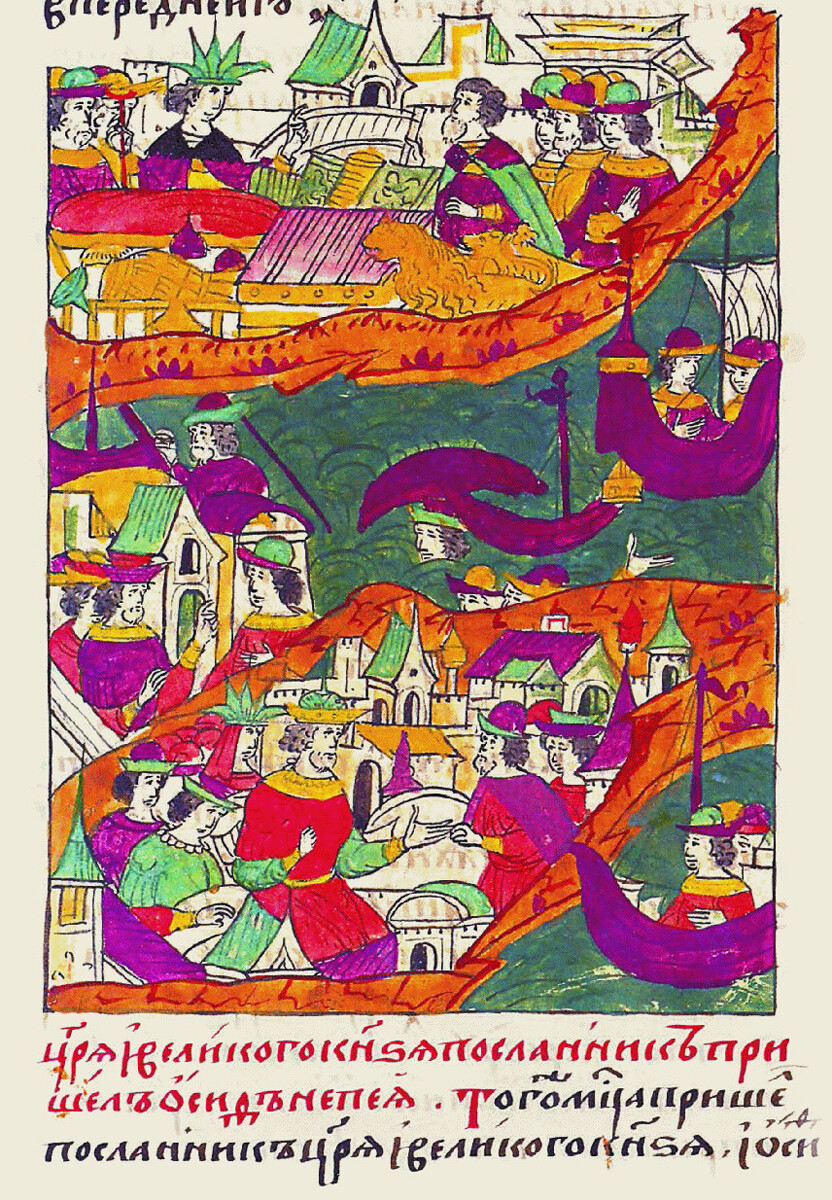

The arrival of Osip Nepeya with lions

Public domainIn 1557, Queen Mary I Tudor of England sent Ivan IV the Terrible a lion and a lioness. The gift was so important that the animals were transported under the personal supervision of Osip Nepeya, Moscow’s envoy to England. The moment of bringing the lions to Moscow was even pictured in the ‘Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible’ (1567).

The Alevisov ravine around the Kremlin in Moscow, Fedor Alekseev, early 19th century

Public DomainIvan the Terrible placed the lions near the Voskresensky Gates of the Kitay-Gorod wall, the gate through which rich guests of the city, including foreign ambassadors, entered the Red Square. The lions were imprisoned in the dried-up moat that ran around the Kremlin walls and they were so famous that even the Voskresensky Gates were later called the ‘Lions’ Gates’. The lions lived long in Moscow and would have lived much longer, if not for the fire in 1571, when Moscow was set ablaze by Crimean Khan Devlet Giray. After the fire, the lions were found dead on the Red Square.

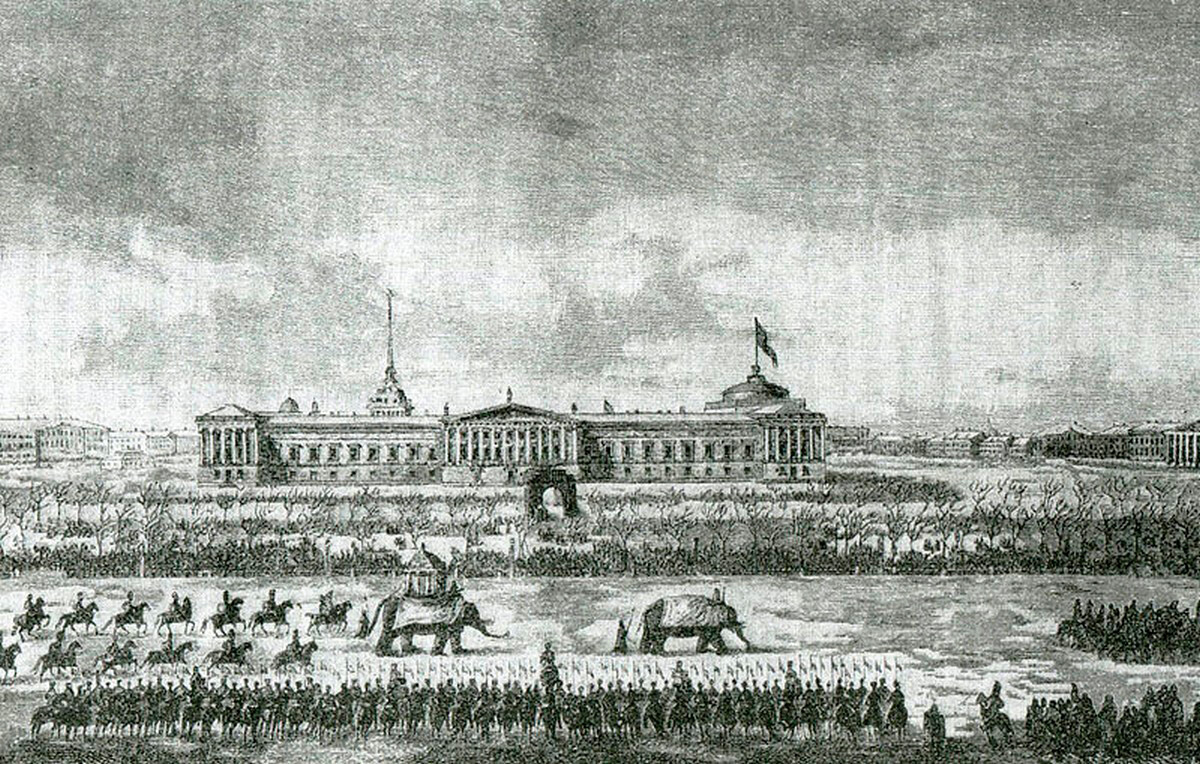

The elephants sent by the persian Shah, the 1740s engraving

Public domainPersian ruler Nader Shah Afshar gave as many as 14 elephants to Elizabeth Petrovna, Peter the Great’s daughter, in 1741. Personally for her, “only” seven elephants – five more of the animals were a gift for the young Ivan VI, who reigned in the Russian Empire from October 1740 and the remaining two – for his mother and regent, Anna Leopoldovna.

The elephants were sent to Elizabeth Petrovna as a marriage proposal. Nader Shah sought a dynastic marriage to cooperate with Russia against Turkey. It seemed to the Persian ruler that Peter’s daughter, excommunicated from the throne, might consider his proposal, which he backed up not only with elephants, but also with a pile of jewels. Of course, it was against all the rules of European diplomacy to make an offer in this way. The gift was accepted, but the Persian ambassador was not even allowed to see Elizabeth. Getting married was out of the question – in October 1741, when the elephants came to St. Petersburg, Peter’s daughter was already planning for a coup d’etat to seize power.

The elephants were settled in the center of St. Petersburg – Karavannaya Street bears its name because a caravanserai, a facility for elephants, had stood on it. Later, the elephants were moved to what is now Vosstaniya Square and were taken to the Neva River for watering along Suvorovsky Prospect, then called Elephant Street.

The 'Temple of Glory' clock made by Michael Maddox, Kremlin Museums

Viktor Velikzhanin/TASSThe unique clock was created toward the end of Catherine the Great’s reign, after 1793, and celebrates her achievements. The clock was made by Michael Maddox, an English engineer who was invited to tutor the heir, Paul Petrovich, in physics and mechanics back in 1766. Maddox stayed in Russia and became famous by founding one of the first public theaters, the Petrovsky Theater in Moscow.

The 'Temple of Glory' clock made by Michael Maddox, Kremlin Museums

Valentina Mastyukova/TASSNot all parts of the clock have survived and the mechanism now works only partially. When the clock was in full working order, it gave a whole performance every three hours. The sun’s halo around the dial would begin to shimmer, because of the movement of the crystal cylinders, while, at the same time, the front flaps of the box, behind which a mechanical waterfall was concealed, would open. The eagles crowning the columns opened their beaks and dropped real pearls into the mouths of their chicks. The clock was also equipped with a metallophone that could play 12 different tunes.

The Orlov diamond in the Scepter of Imperial Russia

Yuri Somov/SputnikThis largest of diamonds found in India is so old that it has had many names, including ‘The Great Mughal Diamond’ (after the empire of the Indian Shahs to whom it belonged) and ‘Mount Sinai’. The diamond was found in India in the early 17th century. It was there until 1738, when Nadir Shah invaded India and took the treasure to Persia. From there, the stone made its way by obscure means to Europe, where it was found in London in the middle of the 18th century.

It is said that the stone was presented to the empress by her favorite guest, Count Grigory Orlov, on November 24, 1773, at a name day party. The Prussian envoy Count Victor von Solms described the event: “Everyone who appeared in the hall, despite the late fall, gave her huge bunches of flowers and some also gave her a souvenir specially prepared for the occasion. One Count Grigory showed up empty-handed. Noticing the discrepancy of his appearance to the general mood, he slapped his forehead and said: “I’m sorry, mother! You have such a holiday today and I, an old fool (Orlov was 39 years – Ed.), completely forgot. Well, don’t be angry, I have something here… It may come in handy… Don’t refuse to accept it.” And, with these words, the count took a flat box from his vest pocket containing a precious diamond.

The truth is much more prosaic – this “gift” Catherine gave to herself. The diamond was bought from an Armenian merchant Lazarev for 400 thousand rubles – a huge sum, which even the favorite of empress could not possess. The diamond was bought by installments for seven years and the empress paid for it from the state treasury. In the same year, 1774, the ‘Orlov’ diamond was inserted in the top of the imperial scepter of the Russian Empire, in which it remains to this day. Its estimated weight is about 190 carats (39 grams). The ‘Orlov’ is a rarity among historic diamonds, for it retains its original Indian rose-style cut.

"The Eagle on The Pine"

Mikhail Fomichev, TASS, the State Museum of Oriental Art‘The Eagle on Pine’ sculpture and its screen were created by Emperor Meiji of Japan as a gift to Nicholas II of Russia on the occasion of his coronation in 1896. The eagle was created by famous Japanese sculptor Kaneda Kenjiro. Now, it is one of the main exhibits at the State Museum of Oriental Art in Moscow, where the sculpture has its own hall. The base of the sculpture is made of wood and covered with ivory feathers – over 1,500 separate parts in all. The head and adjacent feathers are carved from a single piece of elephant tusk and the bird’s claws and eyes are made from horn.

The eagle in Japan, just as in European heraldry, symbolizes power and authority. Obviously, it was the eagle that was chosen as a gift to the monarch of the country whose coat of arms depicts the double-headed eagle. The pine, on which the bird sits, signifies longevity, while the rocks (on the screen) are a wish for inexhaustible fortitude and a long and prosperous reign.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox