“It was dinnertime and we entered the dining room. There was a huge kitchen knife on my aunt’s side of the table and a live chicken was tied to the leg of a chair. The poor bird was kicking and pulling the chair. ‘See?’ the father said to his sister. ‘Knowing that you like to eat living things, we brought a chicken. None of us can kill it, so we left this deadly task for you. Do it yourself.’ ‘Another one of your jokes!’ exclaimed Aunt Tanya, laughing. ‘Tanya, Masha, now untie the poor bird and give her back her freedom.

We hurried to fulfill Auntie’s wish. Having freed the chicken, we served pasta, vegetables and fruits. Auntie ate everything with a great appetite.”

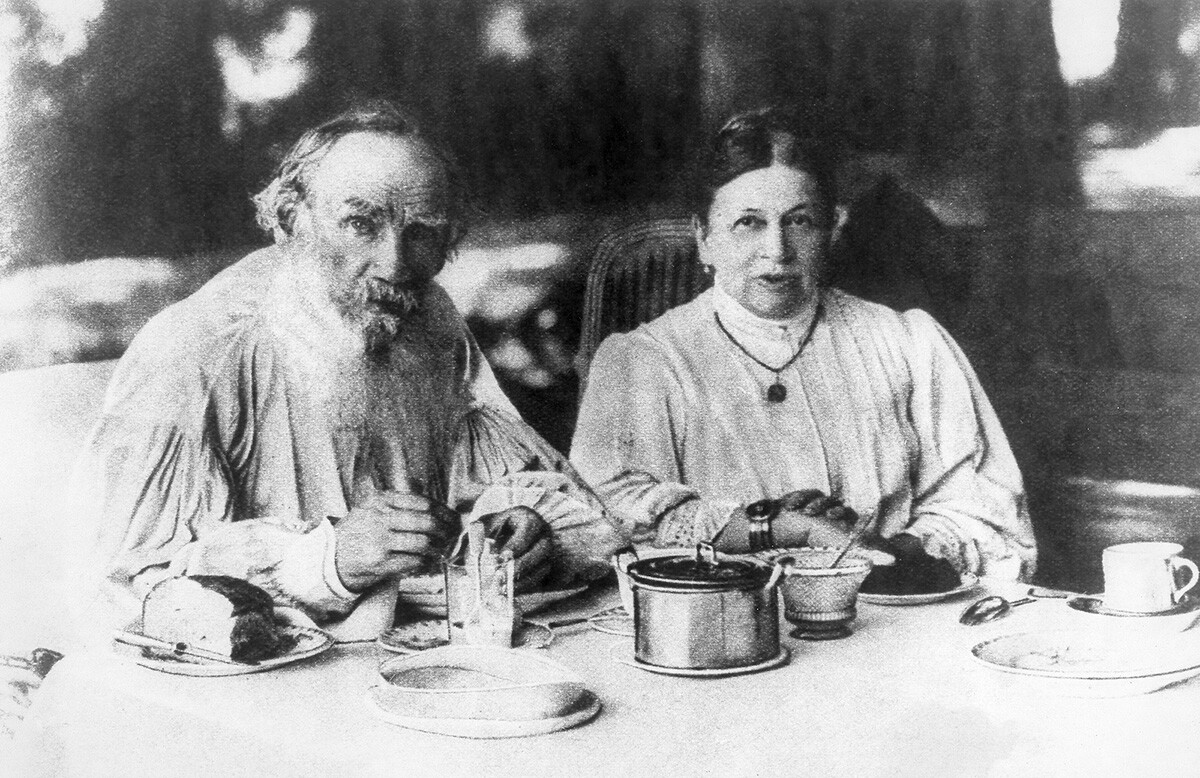

This is an excerpt from the memoirs of Tatiana, Leo Tolstoy’s daughter. She herself, her sister Masha and their father were convinced vegetarians. But, Sofya Andreyevna, the writer’s wife, complained about the writer’s vegetarianism, which for her caused “the complication of a double dinner, extra costs and extra work for people.” In addition, Sophia felt a vegetarian meal “does not nourish him enough.” But Tolstoy persisted and did not eat meat. In Russia, however, he was not the only vegetarian.

Vegetarian canteen on Nikitsky boulevard, Moscow, the 1910s

Public domainNutritionist Jenny Schultz, who opened Hungary’s first vegetarian canteen in 1896, launched one in Moscow in 1903. Having studied Russian attitudes toward vegetarianism, Schultz, who had specifically studied “vegetarian gastronomy” in Switzerland, wrote: “Numerous, mostly long periods of fasting are observed by rich and poor people, in town and in the countryside, with great conscientiousness. This is the reason why the local population is so easily disposed to vegetarianism.”

Indeed, in Russia, fasting has always been given special importance. As Peter Brang, a scholar of Russian vegetarianism, writes: “For Russian monasticism, unlike Western monasticism (with the exception of the Trappists and Carthusians), qualitative fasting – abstaining from eating meat – is a basic provision.” Good monks fasted year-round, only occasionally allowing themselves to eat fish. As for ordinary believers, the four main fasts – the Great Lent, Peter’s, Dormition and Christmas fasts, together with the “usual” fasting days (each Wednesday and Friday) gave a total of about 220 days of fasting a year, which believers also tried to observe.

The Primary Chronicle mentions under year 1074: “Lenten time purifies the mind of man.” And the hagiography of the great Russian saint Sergius of Radonezh mentions that, even as a baby, he did not even touch his mother’s breasts during Lent, thus, his holiness manifested itself in his infancy.

Vegetarian canteen in Gazetny lane, Moscow

Public domainIt turns out that the spiritual ground for vegetarianism in Russia was already prepared. However, the Russian Orthodox Church condemned vegetarianism. In Russia, there were certain Christian sects that completely rejected meat – the Khlysts and the Skoptzy. Since the church actively opposed these sects, vegetarianism also received this bad attitude. The very readiness of someone to abstain from meat aroused the suspicion of church officials that sectarian aspirations might be behind it.

In 1913, Nikolai Lapin, a peasant from Saratov region, submitted his article ‘Why I Became a Vegetarian’ to the Vegetarian Review magazine. Lapin gave up meat at the age of 18, because, since childhood, he was disgusted to see cattle being slaughtered. Soon, his fellow villagers, Lapin wrote, began to question whether he could do the hard farm work and when there was no problem with that, they began to say that he had been seduced by the devil. So, the vegetarian diet raised questions among the common people, as well, not only Tolstoy’s wife, who reproached the count that because he taught his daughters "not to eat meat – they eat vinegar and oil, they became green and thin.”

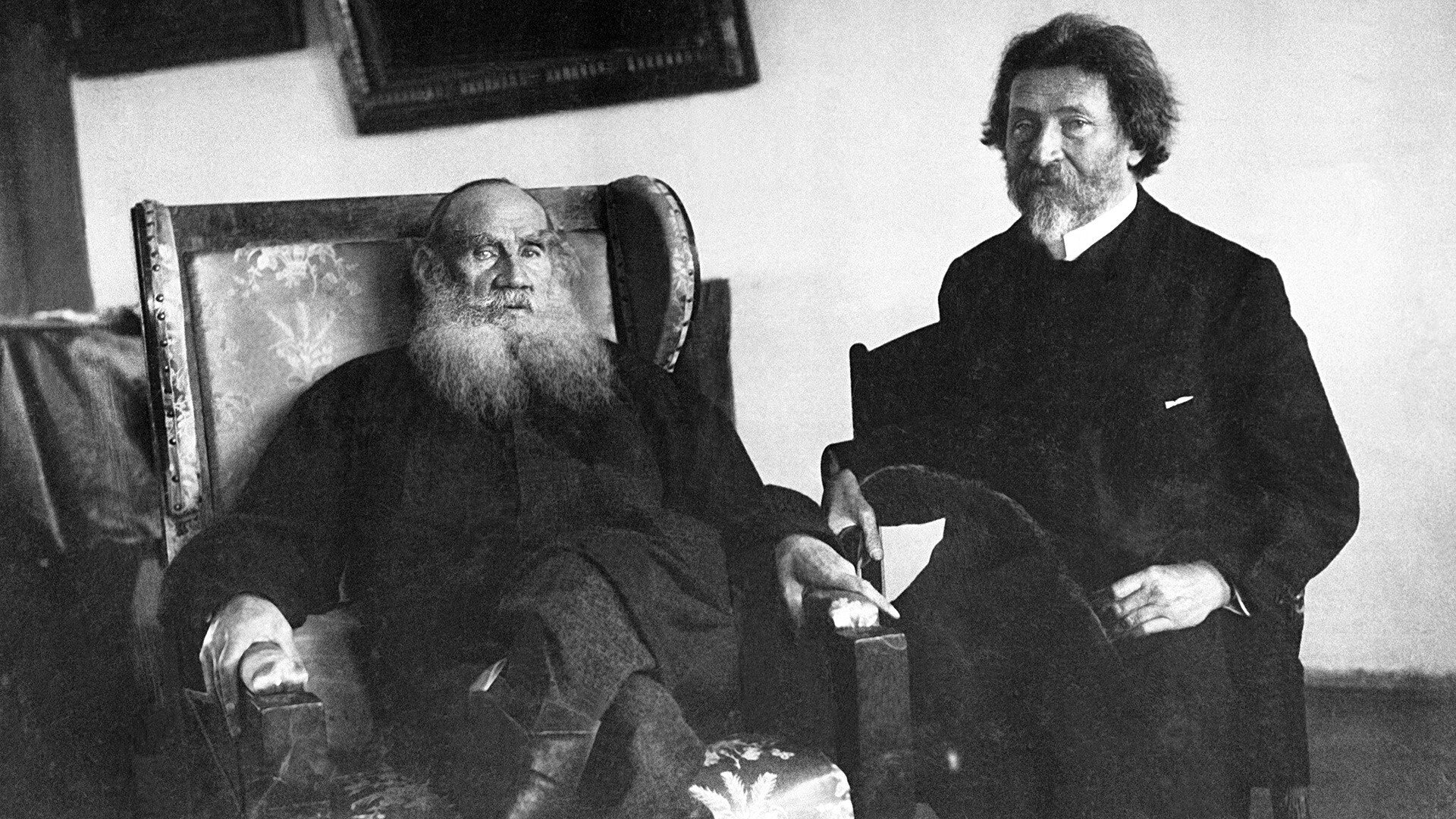

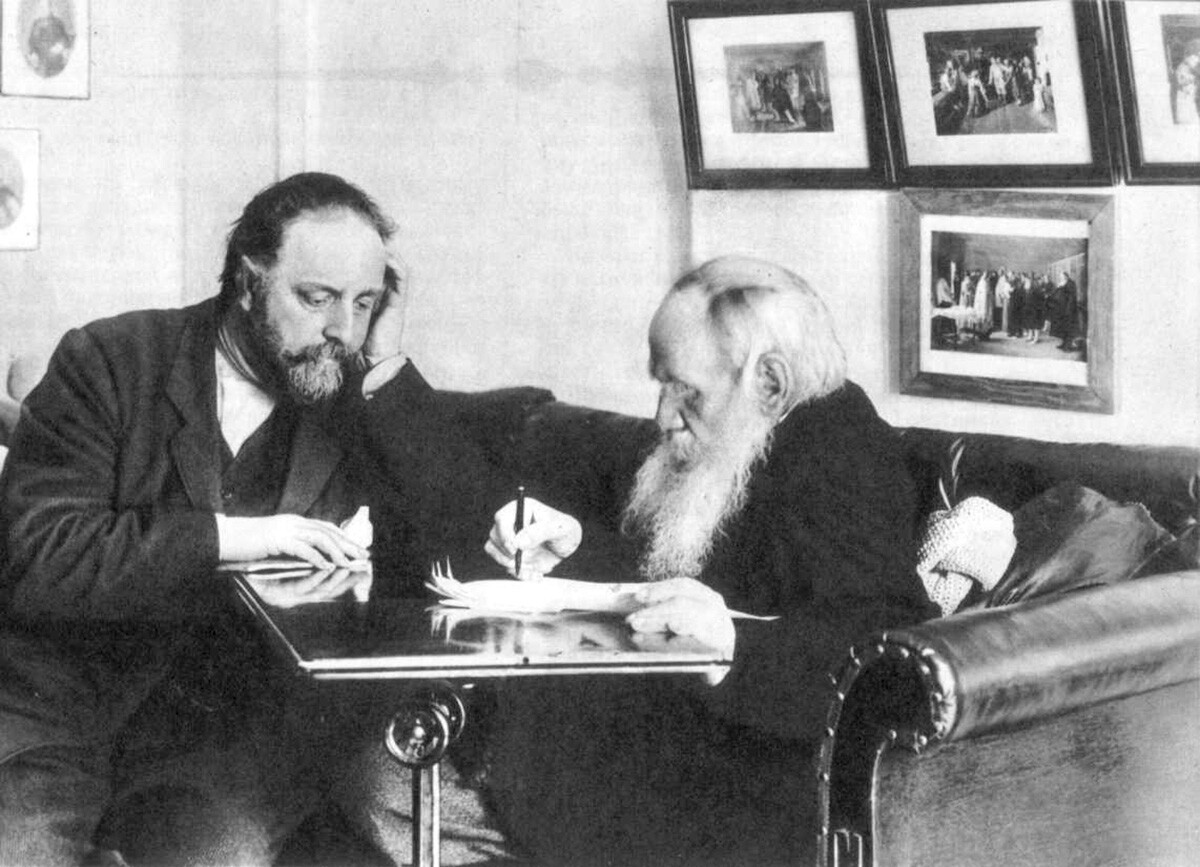

Leo Tolstoy and Ilya Repin in Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy family estate

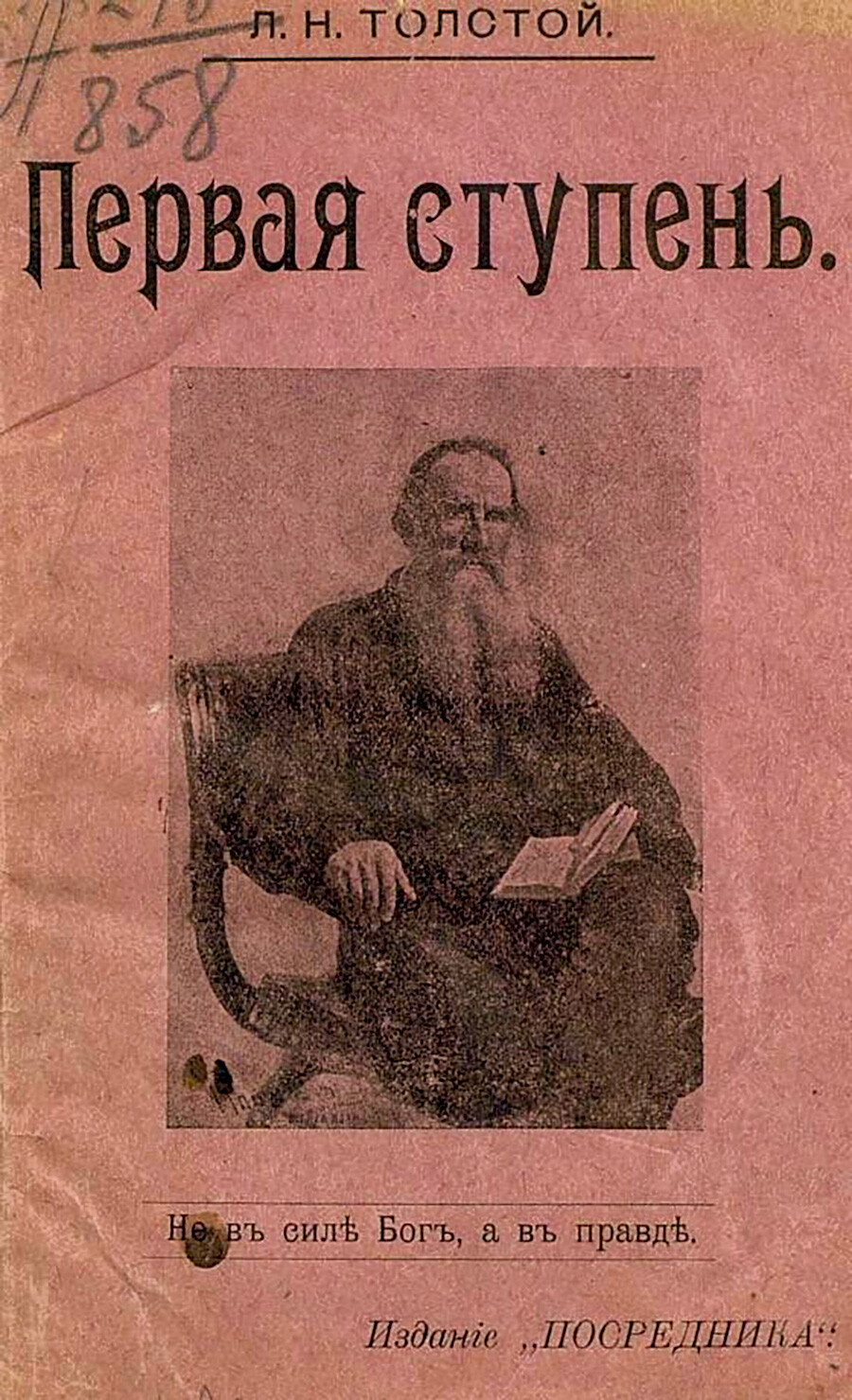

TASSCount Tolstoy said that he rejected meat around 1883-1884, when he met aristocrat and retired military officer Vladimir Chertkov, who was already a vegetarian. In 1885, the writer was already in conflict with his wife, because of his refusal to eat meat and, in 1892, he wrote an essay titled ‘The First Step’ – a passionate manifesto of vegetarianism. “How is it possible to kill a cow that has been feeding milk to you and your children for years? The sheep that warmed you with its warm wool? Take it – and kill! Cut the throat and eat it?” Tolstoy asked.

Leo Tolstoy, "The First Step"

Public domain‘The First Step’ had a huge impact – many intellectuals turned to vegetarianism. Artist Ilya Repin enthusiastically described his vegetarianism: “The eggs were thrown away (the meat had already been left before). Salads! What a charm! What a life (with olive oil!) Soup from hay, from roots, from herbs — that’s the elixir of life. Fruits, red wine, dried fruits, olives, prunes… nuts are energy. Is it possible to list all the luxuries of a vegetable table?” In 1900, Repin married Natalia Nordman, one of the famous Russian propagandists of vegetarianism, who, in addition to refusing “slaughter” in food, did not wear furs, which completely shocked the noble society.

Leo Tolstoy and his wife Sofya at a dinner table

Public domain“Here, vegetarianism is mostly viewed from the ideal side; the hygienic side is still little known," Jenny Schultz noted in her article. Indeed, the first Russian vegetarians underlined not the harm of meat for health. Protest against murder was at the core of their ideas, that’s why the vegetarian food was dubbed “slaughter-free”.

Vegetarianism in Russia appeared even before Tolstoy. Tolstoy’s follower Yuri Yakubovsky wrote that, in 1888-1889, the first vegetarian society called ‘Neither Fish nor Meat’ celebrated its 25th anniversary in St. Petersburg. So, already in the 1860s, vegetarians were united among themselves – but, so far, without scientific justification. It appeared in 1878, when an article titled ‘Human nutrition in its present and future’ was published by the rector of St. Petersburg University, botanist Andrey Beketov. The author argued that man is naturally adapted to plant-based nutrition, pointed out the high cost of meat and also reminded that the slaughterhouse is “a disgusting, stinking and bloody place where they cut, tear, chop and drain blood from veins”. “The future belongs to vegetarians,” concluded Beketov. But, even the rector’s authority could not convince the public – several mocking refutations came out on Beketov’s article.

Leo Tolstoy with his friend Vladimir Chertkov, who probably introduced him to vegetarianism

Public domainHowever, after the publication of ‘The First Step’, attitude towards Beketov changed. His article was reprinted twice, with a total circulation of about 15,000 copies, in the publishing house of Vladimir Chertkov ‘Posrednik’. In 1903, a collection compiled by Tolstoy, ‘Slaughter-free nutrition, or vegetarianism. Thoughts of different writers’, which contained 250 quotes about the benefits of vegetarianism, was published there.

The first private vegetarian canteen of English couple Mr. and Mrs. Mood opened in Moscow in 1896 – but almost immediately closed. In 1904, there were already four such canteens. Portraits of the “sun of Russian vegetarianism” – Leo Tolstoy – hung on the walls. By 1914, according to Brang’s calculations, there were 73 vegetarian canteens in 37 cities, most of all in St. Petersburg (nine) and seven each in Kiev and Moscow.

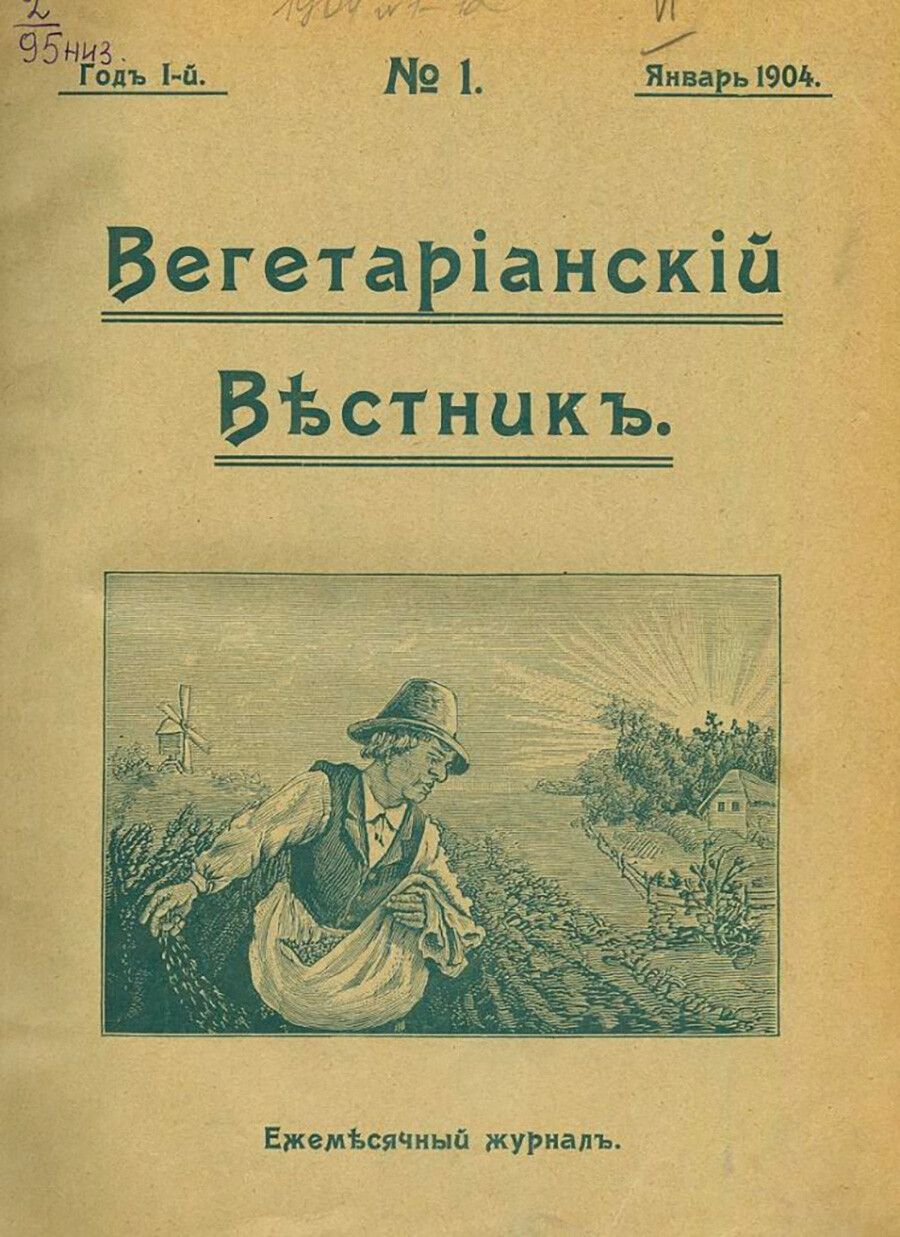

"Vegetarianskiy vestnik" ('The Vegetarian Herald') magazine

Public domainCanteens were quite popular – one Moscow canteen in Gazetny Lane served up to 1,300 people a day. Statistics on visits to the canteens of the Moscow Vegetarian Society showed an increase in the number of guests from 11 thousand in 1909 to more than 642 thousand in 1914. And, for example, the Kiev Public Vegetarian Canteen in 1911 served 489,163 meals to 200,326 visitors. The magazines ‘Vegetarian Review’ and ‘Vegetarian Bulletin’, as well as the almanac ‘Natural Life and vegetarianism’ were published.

It was in the last years before the revolution that vegetarianism in Russia became widespread and commonplace. But, this development was broken by the offensive of Soviet power. In the first years after the revolution, the Bolsheviks did not pay attention to vegetarians, but, in 1929, the Moscow Vegetarian Society was banned and a number of its members were exiled – for the Soviet government, these were “Tolstoyans”, carriers of the ideology of non-resistance and nonviolence, which had to be eradicated and which was done throughout the country under the pretext of fighting the “Tolstoyans” like with fists. In the USSR, as the Great Soviet Encyclopedia claimed in 1951, vegetarianism “has no adherents”. The vegetarian society in Moscow was registered again only in 1989.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox