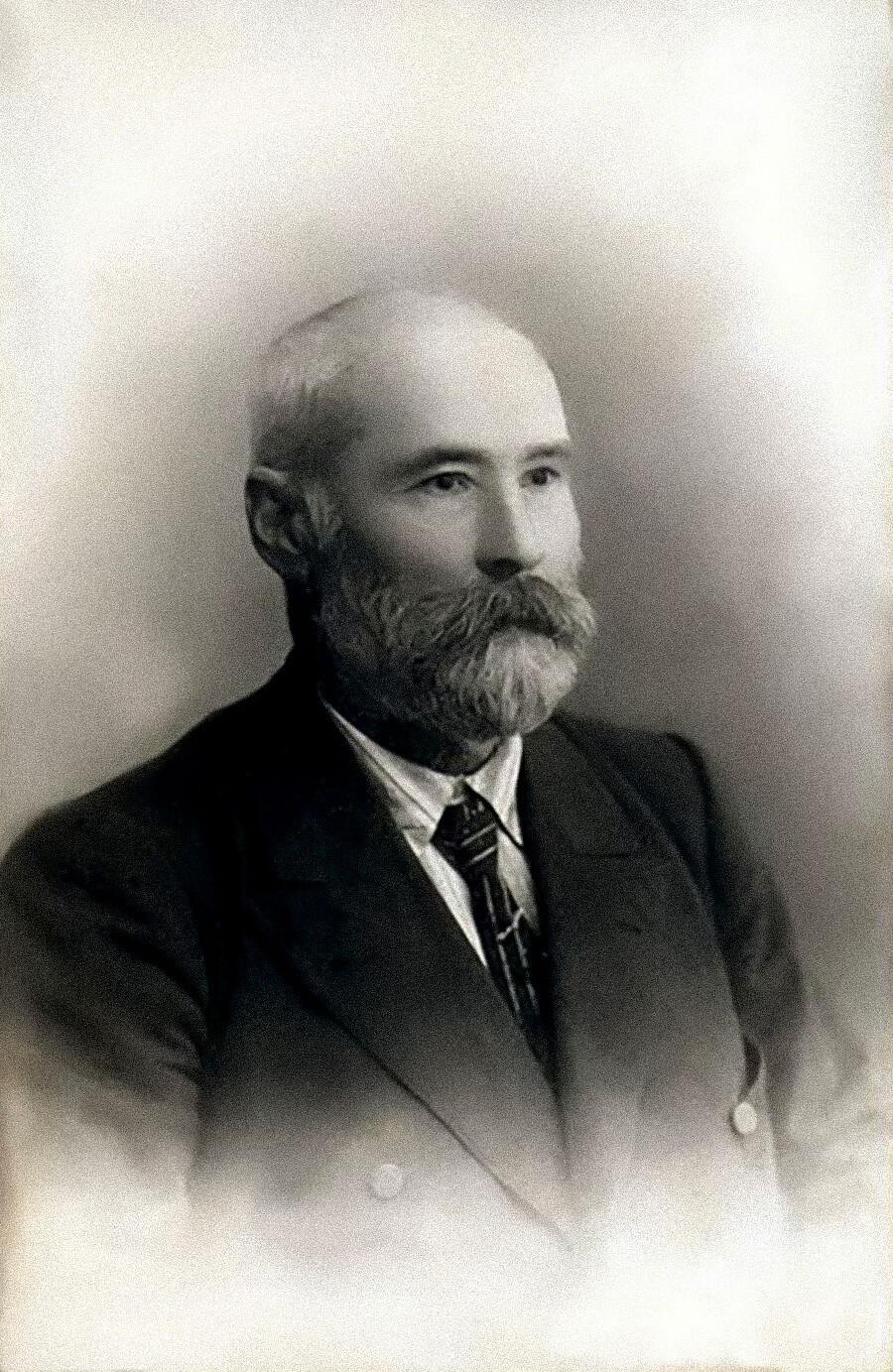

Born into a prominent noble family, Adam Rzewuski (known in Russia as Adam Adamovich Rzhevusskiy) served Russia faithfully and loyally all his life. Having started his military career as a humble cadet, he rose to the rank of cavalry general and even became a member of the retinue of His Imperial Majesty.

Rzewuski participated in all the key battles of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829, during which he was badly concussed by a cannon ball and received a bullet wound in the left leg. For his courage on the battlefield, the ‘Order of Saint Anna’, 3rd class, and the ‘Order of Saint Vladimir’, 4th class, were bestowed on him.

During the November Uprising of 1830-1831 in Poland, which set itself the aim of restoring the independence of the “historical Rzeczpospolita” [Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth], Adam Adamovich remained loyal to the Russian Empire and was actively involved in the suppression of the revolt. Seconded to Ivan Diebitsch-Zabalkansky [Hans Karl von Diebitsch], the commander of Russian troops, he was irreproachable in carrying out the latter’s most difficult orders and was awarded a gold sword inscribed “For bravery”.

At different times, Rzewuski participated in the Crimean War of 1853-1856, commanded cavalry divisions, as well as the troops of the Kiev Military District and was in charge of the ‘Alexander Committee for the Wounded’. The Russian tsars greatly appreciated the loyalty of the fearless Pole and invariably included him in the circle of their confidants.

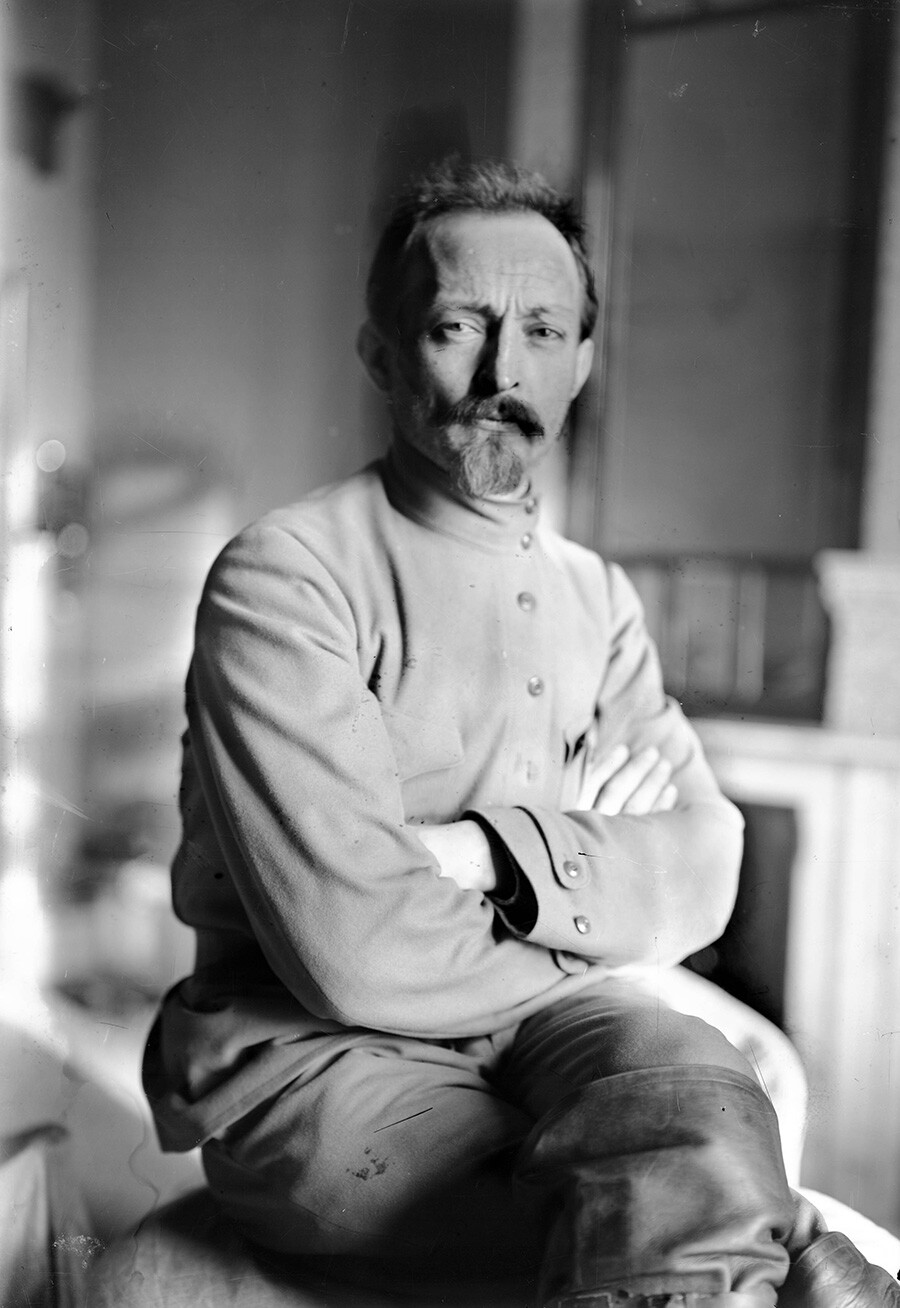

Like Rzewuski, Felix Antonovich Krukovsky, a native of the Grodno Province, was a born military man. In 1839, at the age of 35, he found himself in the Caucasus, where the Russian army was then engaged in a continual bloody struggle against recalcitrant highlanders.

In 1843, Krukovsky distinguished himself by repelling a night attack by a 4,000-strong enemy detachment at the settlement of Bekeshevskaya, having only 400 Cossacks under his command. Six years later, he was appointed interim ataman of the sizable Caucasus Line Cossack Host, which, at the time, along with the Black Sea Cossack Host, was one of the main forces in the mastering of the North Caucasus.

The Cossacks respected and loved Felix Antonovich not only for his bravery on the battlefield and excellent administrative skills, but also for the respectful attitude that he showed towards them and their customs. For example, although being a Catholic, he invariably attended Orthodox Church with them on Sundays.

Krukovsky was killed in a skirmish near the fortress (now town) of Urus-Martan in 1852. “If one were to choose a thousand of the best men from the host and to take from each of these men their best virtues and qualities, even then their sum total would not outweigh the qualities possessed by the late ataman, absolutely irreplaceable for our Caucasian Cossacks.” So wrote His Serene Highness Prince Mikhail Vorontsov, the Viceroy of the Caucasus, about Felix Krukovsky.

In 1863, 21-year-old Polish agricultural student Michał Jankowski joined another large-scale uprising against Russian rule that broke out in the former lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. After the rebels were defeated, he was deprived of his title of nobility and all his fortune and was sent for hard labor to Siberia for eight years.

After a while, many of the exiled Poles, including Jankowski, were pardoned, but they were still forbidden to return to their homeland. Michał whiled away the long days hunting until he managed to join a scientific expedition along the River Amur to the Pacific coast. The voyage changed the life of the former rebel forever. Falling in love with the Far East, he decided to stay there for the rest of his life.

Jankowski, who started going by the Russian name of Mikhail Ivanovich, proved to be a talented entrepreneur. First, he obtained the position of manager at a gold mine on Askold Island, 50 km from Vladivostok, and then he set up a stud farm on Sidemi Peninsula near Korea, where he developed a new breed of horses adapted for the conditions of the Far East. Also there, the enterprising Pole set up Russia’s first plantation of ginseng, a highly valued medicinal plant in traditional oriental medicine.

Science was Jankowski’s second enthusiasm after commerce. He discovered several species of beetle and around 100 species of butterflies and moths, 17 of which were named after him. He also researched and described a rare bird living only in the Far East, known today as Jankowski’s bunting. The archeological culture of the southern Maritime Territory that was discovered by Jankowski was also given his name.

Born into the Polish petty gentry in the village of Dzerzhinovo, situated not far from Minsk, Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky was to become one of the originating figures of the Soviet state security bodies. Nicknamed ‘Iron Felix’ for his strength of character, he was a co-founder and first head of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage (VChK) - the precursor of the USSR’s KGB and the Russian Federation’s FSB.

Dzerzhinsky was one of the ideologues and organizers of the so-called Red Terror mounted against the enemies of the Revolution, which consisted not just of intimidation and arrests of representatives of circles opposed to the Bolsheviks, but also their physical elimination.

At one point, Felix Edmundovich fought against his former fellow countrymen. In the Soviet-Polish War of 1919-21, he served as rear services chief of the Southwestern Front and was also a member of the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee - a government organized by the Bolsheviks on Polish territories occupied by the Red Army.

“Dzerzhinsky was the sternest critic of his own brainchild… He was constantly taking apart and restructuring the ‘Cheka’ [Soviet secret police prior to NKVD and the KGB - Ed.]; time and again, he would re-examine its people, structure and methods, wary above all of the risk of red tape, paper-pushing, indifference and hackwork taking hold in the VChK-OGPU…” This was the description of his close associate given by Vyacheslav Menzhinsky (also a Pole), who replaced ‘Iron Felix’ as chief of the Soviet special services following the latter’s sudden death in 1926.

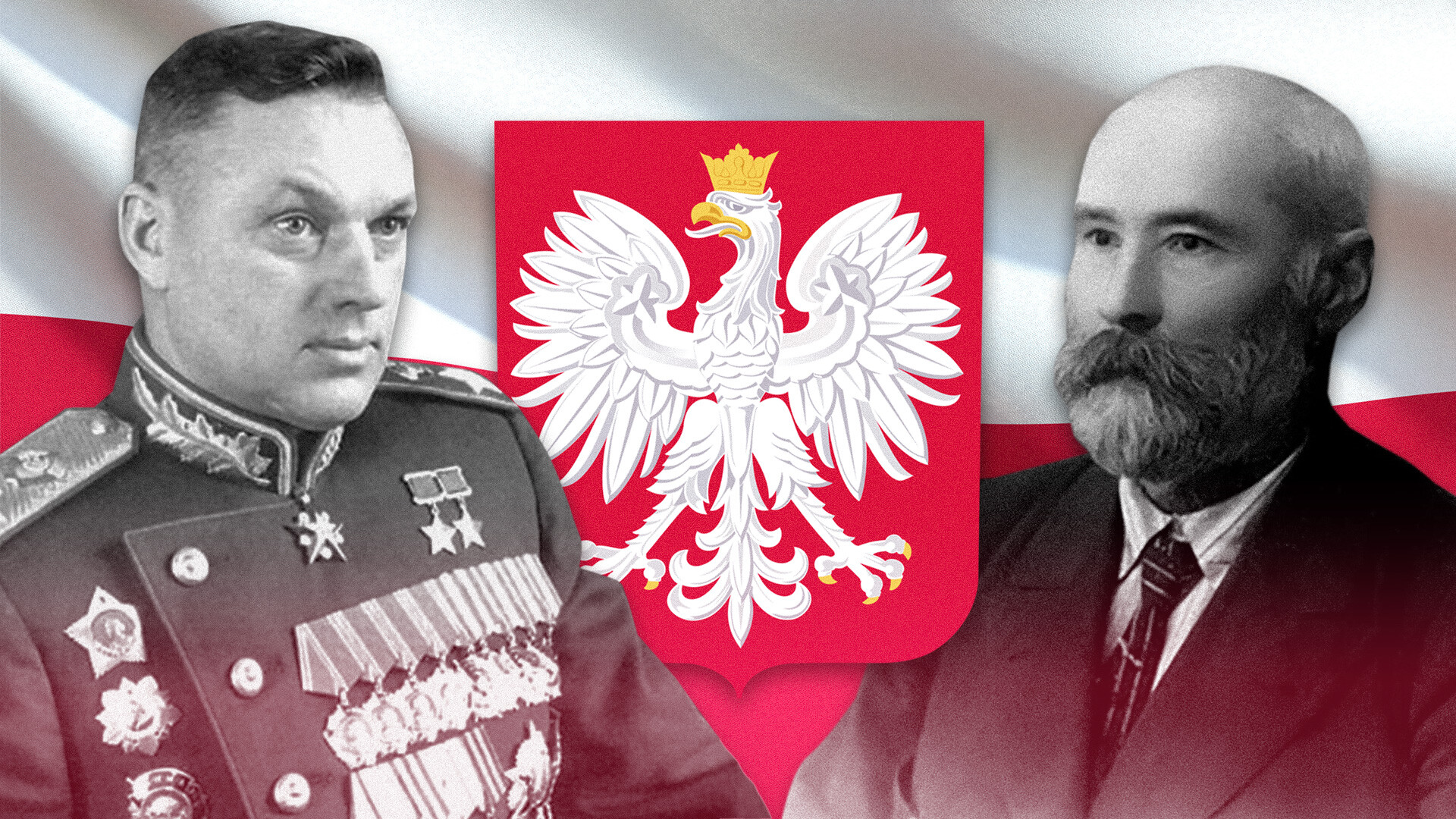

“I am the most unfortunate Marshal of the Soviet Union. In Russia, I was regarded as a Pole and, in Poland, as a Russian,” lamented Warsaw-born Konstantin Konstantinovich Rokossovsky, the son of a Polish railway official father and a Russian teacher mother, who was destined to become one of the best military commanders of World War II.

After the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, Rokossovky, who had been serving in the 5th Kargopol Dragoon Regiment, faced a difficult choice: Either to fight for the restoration of the Polish state or to devote himself to the struggle for the “rule of the workers and peasants”. Choosing to side with the Bolsheviks, he was subsequently to make a glittering career in the Red Army.

Avoiding death against all odds in the period of the ‘Great Terror’ in the second half of the 1930s (he was accused of working for Polish intelligence and was only released after two and a half years of languishing in various prisons), Rokossovsky was serving as commander of a mechanized corps in the rank of major-general when the Wehrmacht invaded.

He gave a good account of himself in the defensive battles of summer and fall, 1941, took part in the large-scale counteroffensive by Soviet troops outside Moscow and was one of the architects of Operation Uranus to encircle and destroy Friedrich Paulus’s 6th Army at Stalingrad.

In 1944, Rokossovsky commanded the 1st Belarussian Front, which in the course of ‘Operation Bagration’ smashed the troops of Germany’s Army Group Center, advanced 600 km to the west and liberated the entire territory of Byelorussia and part of the Baltic region and eastern Poland. On June 29, Konstantin Konstantinovich was awarded the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union.

Rokossovsky was supposed to take Berlin, but, at the last moment, Stalin re-assigned him to the 2nd Byelorussian Front operating in East Prussia and Pomerania, while the 1st Byelorussian Front was put in the hands of the Red Army’s most brilliant commander, Georgy Zhukov. “To what do I owe this disfavor?” asked the aggrieved marshal on learning of the decision, to which the ‘Father of the Peoples’ replied: “It’s no disfavor - it’s politics.”

In 1949, on a proposal of the Polish authorities and with the permission of the Kremlin, Konstantin Rokossovsky became Poland’s minister of national defense, a post which he held until 1956. He was the only Soviet marshal in history to additionally become a marshal of Poland.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox