The translation center at the Nuremberg trials

Bettmann Archive/Getty ImagesDuring the Nuremberg trials, namely the questioning of Fritz Sauckel, labor commissioner at the Four Year Plan office, the Soviet interpreters had an incident. Defendant Sauckel flew off the handle and started shouting, with Thomas Dodd, deputy of the chief prosecutor from the U.S., coming up with further evidence of Sauckel’s guilt. Both did it so emotionally, that their vibes spread on to the Soviet interpreters.

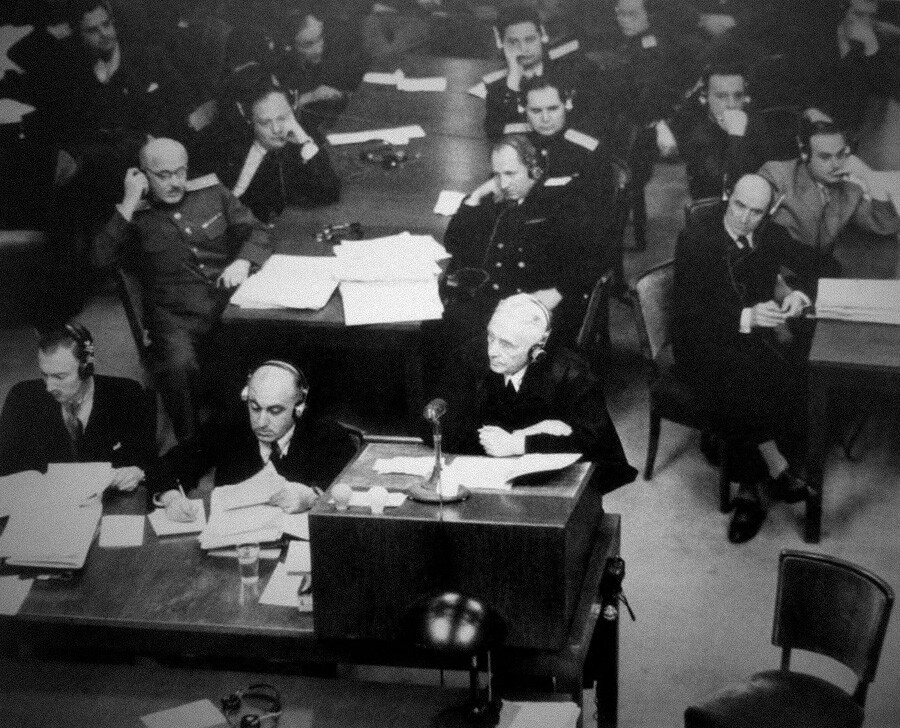

Courtroom of International Military Tribunal

Raymond D'Addario/U.S. ArmyThis is how it was described in a book by Tatiana Stupnikova, who interpreted Sauckel at the time:

“…We jumped off our chairs and stood in the interpreters’ ‘aquarium’, my colleague and I having a loud and tough exchange, akin to the dialogue between the prosecutor and the defendant. <…> My co-interpreter grabbed my arm, just above the elbow, and, addressing me as loud as the anxious prosecutor, repeated, but in Russian: ‘You must be hanged!’ And I, all in tears from the pain in my arm, shouted in response, in chorus with Sauckel: ‘I should not be hanged! I’m a worker, I’m a seaman!’”

The exchange was interrupted by British judge Geoffrey Lawrence, who went on to say: “Something wrong has happened to the Russian interpreters. I’m closing the session.”

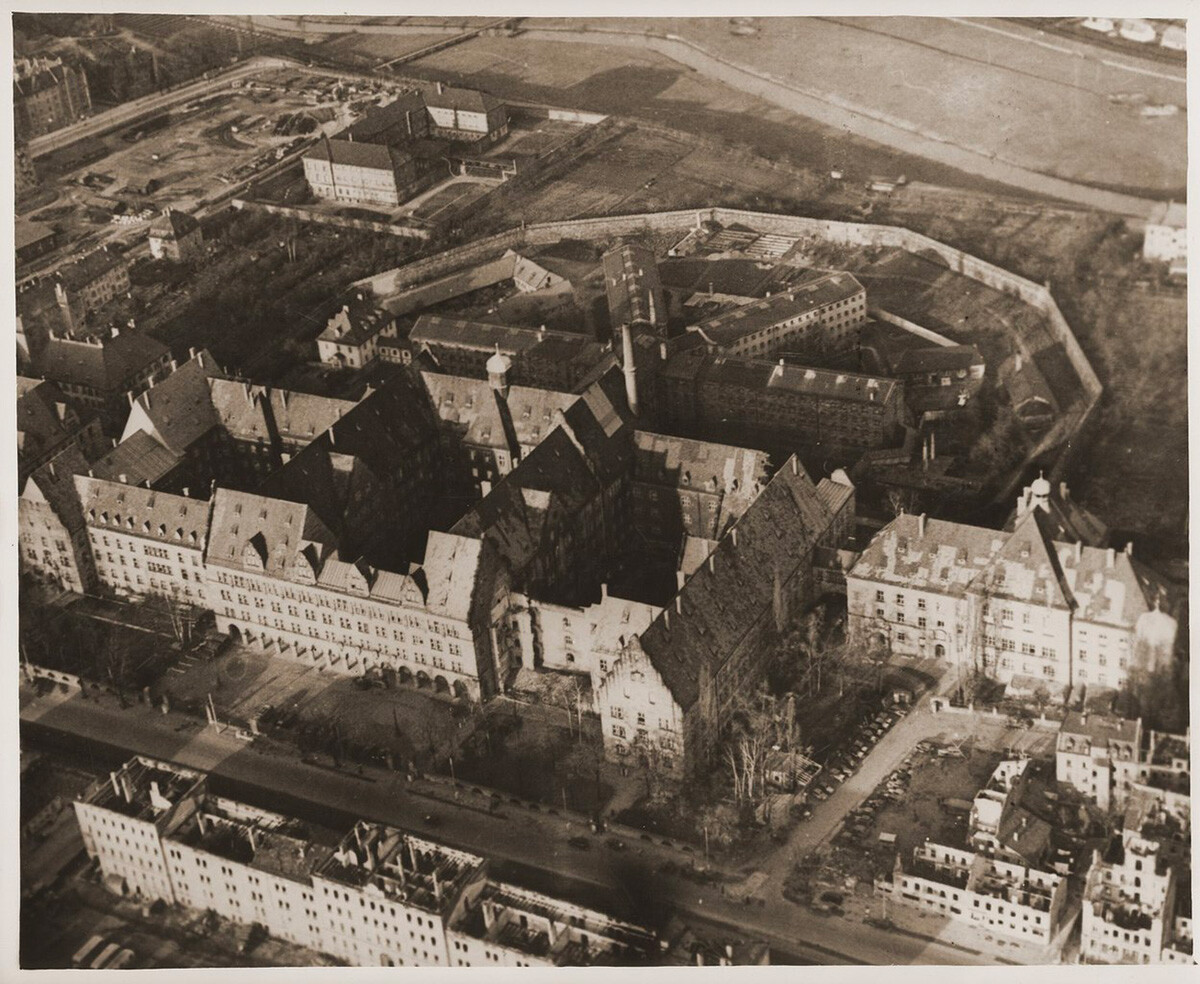

Palace of Justice in Nuremberg

Public domainSimultaneous interpretation in court was never provided before the international Nazi crimes tribunal in Nuremberg; there was only written translation and oral consecutive interpretation before that. Thus, these historic trials, which spanned almost a year - from November 20, 1945, until October 1, 1946 - became a real challenge for interpreters, as booth interpretation is conducted simultaneously with the perception of what the speaker says.

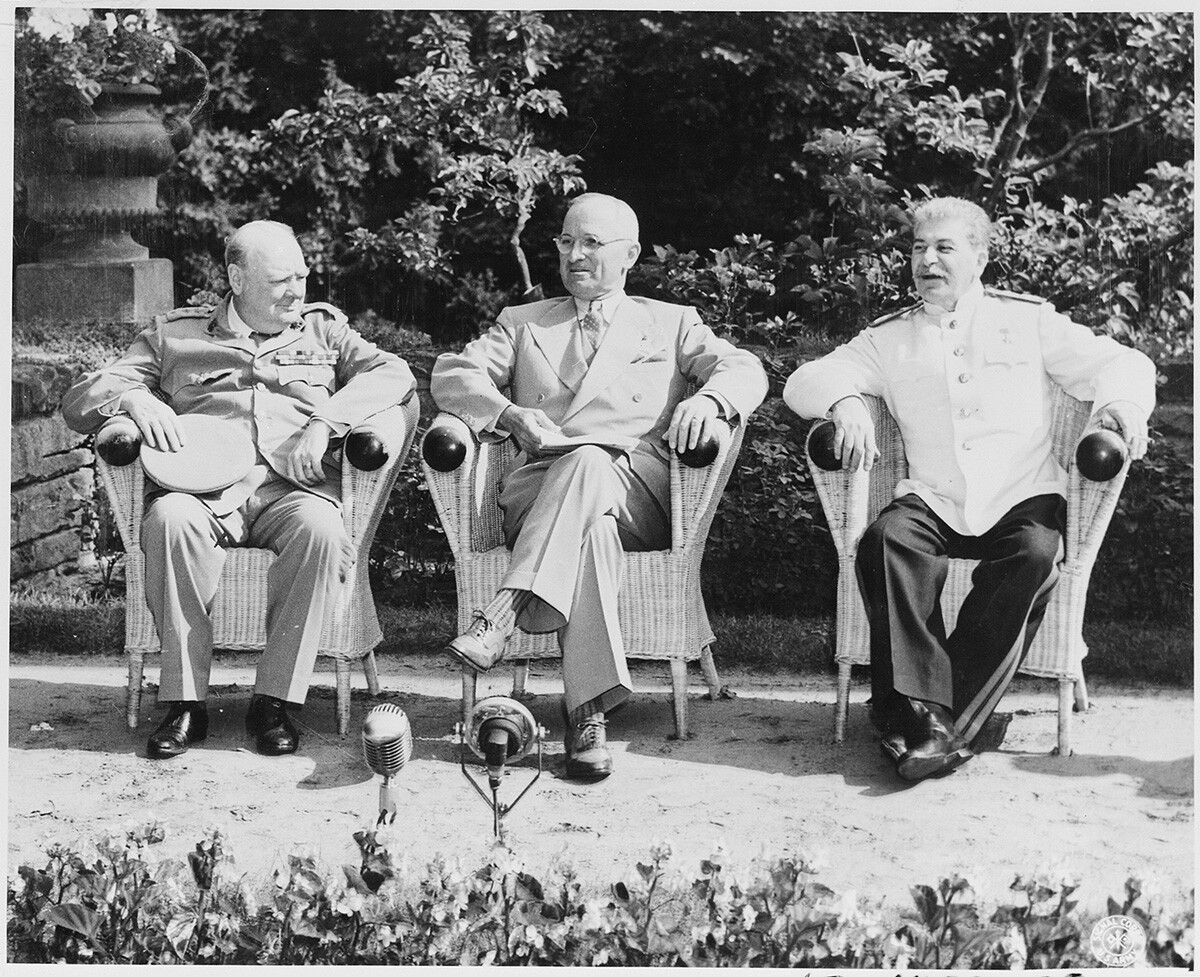

In the Summer of 1945, at the Potsdam Conference, it was decided to divide Germany into four occupation zones. Nuremberg turned out to be under the U.S. control and the tribunal was to be facilitated by American personnel. This is the reason why, as recalled by the trial participants, the Soviet delegation arrived without interpreters.The Americans were expected to provide translation into four languages - Russian, German, English and French. Yet, the assumption proved wrong. The NKVD was put in charge of an urgent search for specialists. The People’s Commissariat managed to find them at short notice and the interpreters were sent to Nuremberg right before the tribunal started its work.

Pictured L to R: British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, President Harry S. Truman, and Soviet leader Josef Stalin during the Potsdam Conference in Germany

National Archives and Records AdministrationThe Soviet specialists working at the trials had different qualifications. Apart from qualified interpreters, there were also teachers, economists and emigrants’ descendants, who had been taught several foreign languages since childhood.

The major condition for a simultaneous translator’s work is a soundproof booth, as extraneous noises distract a lot. During the Nuremberg trials, nothing of the kind was provided. The interpreters’ workplace was open from above, had glass panels on three sides and was too close to the defendants’ bench. This played a special role, since it is important for interpreters to watch the behavior of those they are translating.

On the outside, it all looked like a glass aquarium - this is how it was nicknamed. The “aquarium” consisted of four three-seat booths. Each interpreter had their own headphones; however, there was only one microphone in each booth, which the interpreters passed to each other.

Nuremberg International Military Tribunal: interpreters section

Raymond D'Addario/U.S. ArmyThe work of a simultaneous interpreter is stressful per se, as they have to translate incoming information at the same time with what the speaker says, by no means missing a single detail. However, the trial of the Nazi criminals put an additional psychological pressure on it, as the terrifying details of Nazi crimes were voiced.

The Soviet translators were snowed under with work. The interpreters from Germany had the biggest workload, as they had to interpret the indicted Germans, their lawyers and the witnesses, who were largely German, as well.

Soviet interpreter Tatyana Ruzskaya

Public domainThe workload of interpreters from English was also extensive: they interpreted the English and American prosecutors and judges, including tribunal chairman. Geoffrey Lawrence.

French was rarely spoken in the courtroom and the interpreters sat in their “aquarium” silently, waiting for any remarks made in the language.

At some point, Moscow sent a teacher of German from the law faculty of Moscow State University as an interpreter. In the courtroom, she experienced a genuine pedagogical shock after a remark made by Dr. Otto Stahmer, Hermann Göring’s barrister. Responding to the judge’s question about how much time he needed to present the documents and make a concluding speech on his defendant’s case, Dr. Stahmer said:

“ Dr. Stahmer [stamer] - sieben Stunden.”

It contradicts the phonetics of the German language, where the letter combination ‘st’ is pronounced as ‘scht’. The anxious barrister, thus, appeared to shift to his native northern dialect. While listening to his speech, the interpreter repeated time and again: “I give my students unsatisfactory marks for this mistake!”

Dr. Otto Stahmer, Hermann Göring’s barrister

Public domainThere were cases when the accused corrected the interpreters. For instance, Alfred Rosenberg, head of the Nazi Party’s foreign policy office, who had an excellent knowledge of Russian, admonished a German woman who was translating from Russian.

“Not the paintings featuring the image of God - Gottesbilder, but the icons - Ikonen, sweetheart!” he exclaimed in good Russian. The interpreter got scared and she was shortly replaced with a Soviet specialist.

A speaker’s monologue could last an hour or even longer, so an interpreter from their language focused as much as possible on it, while the other two could listen with half an ear, so as not to miss out on a remark in their own working languages.

Arkady Poltorak, who headed the secretariat of the Soviet delegation at the military tribunal, recalled in his memoirs:

“The interpreters - the Americans, Englishmen and the French - would typically read some gripping book or just relax in this situation. But, our team would always listen to the speaker together and help the one interpreting as much as they could.”

Interpreters had also a lot of paper work

Yevgeny Khaldei/Russian State Film and Photo ArchiveEven a perfectly experienced simultaneous interpreter is slightly behind a speaker, so, when the latter enumerated something, mentioning a whole range of names or numbers, the Soviet interpreters jotted everything down on a sheet of paper, so that their colleagues could read out the notes in case it was needed.

Later on, this team spirit spread on to other delegations, as well. Poltorak pointed out that it was “a triumph of our morality, albeit a little one”.

Besides, after their working day was over, the Soviet simultaneous interpreters gave a helping hand to their colleagues engaged in written translation, as the load of written work was huge and there was a shortage of specialists. Merely around 40 translators worked for the Soviet delegation, whereas no fewer than 640 did for the American one.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox