There's nothing like a good old Soviet queue.

Boris Yelshin / Sputnik

Believers crowd for the service in the village church of the Holy Cross, May 1950, Yaroslavl region, Russia

Anatoliy Akilov/Russia in photoThe Soviet government led a staunch anti-religion campaign. “We must fight religion,” Lenin used to say – and that became the goal of atheist propaganda for years to come. Immediately after the Revolution, in 1918, the Orthodox Church was ‘separated from the state’ – marriages, births and deaths were no longer registered by the church, but through the respective civil bodies of the Soviet republics. Meanwhile, churches in the USSR were either destroyed or repurposed, while almost all mosques were also closed.

Despite all that, religion was never formally banned in the USSR. The Soviet Constitution stated that “Citizens of the USSR are guaranteed freedom of conscience, that is, the right to profess any religion, or not to profess any, [and] to participate in religious cults or conduct atheistic propaganda.”

In 1943, the Moscow Patriarchate was restored, and the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church was created at Joseph Stalin’s initiative. The state in fact acknowledged the existence of Orthodox believers. So, although atheist propaganda was all around, believers were not banned from visiting churches – it just became very hard to do.

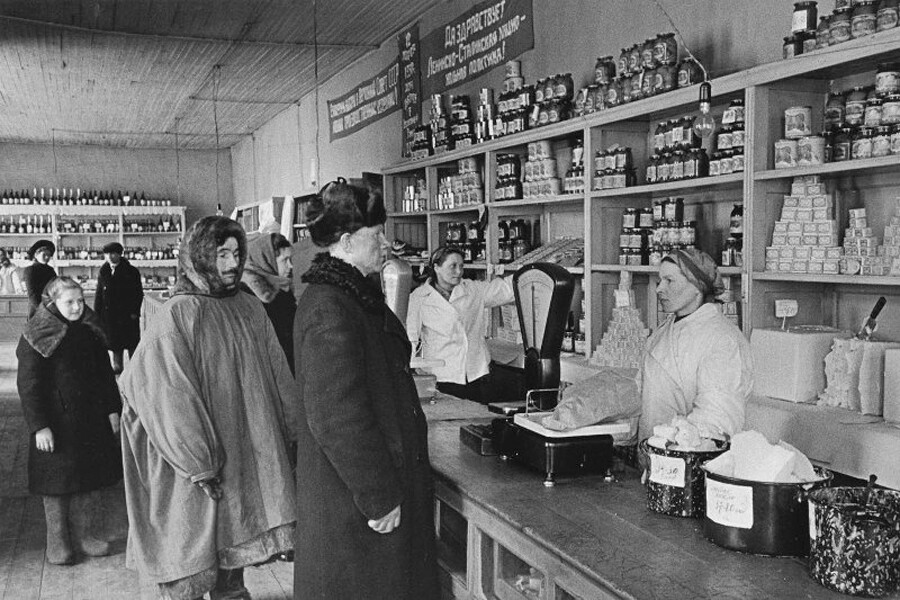

At a local store, Arkhangelsk region, 1949

Georgy Lipskerov/MAMM/MDF/Russia in photo“From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” was a slogan popularized by Karl Marx and propagated in the early years of the USSR. However, social disparity was very strong from the very beginning. The housing problem was felt acutely. However, mass construction only began under Nikita Khrushchev, after the war. Even after that, most workers were living in rather modest conditions, and even such apartments were hard to get: the flats couldn’t be bought, they were given out by the state. Even buying a car or a piece of furniture could take years of being on the waiting list – that is, if you had the money. Only high-ranking party officials enjoyed some level of luxury.

August 13, 1988, patients in the queue at the children's polyclinic, Orenburg, Russia

Valeriy Bushukhin/TASSThe USSR indeed organized a healthcare system that was free for all citizens, even boasting the highest number of doctors per citizen (in 1975, there were 32 medical workers for every 10,000 citizens in the USSR – compared to only 21 in the U.S.). However, most of these doctors lacked experience and were mostly pooled from low-salaried nurses and paramedics.

There are two undeniable truths that condemn the Soviet healthcare system. Firstly, in the USSR it was quite common to spend weeks, even months, at the hospital waiting for surgery. Hospitals were most often overbooked, with patients lying on strollers in halls. And surgeries were performed slowly due to the shortage of qualified personnel.

READ MORE: Was everything perfect with the Soviet healthcare?

Secondly, there were corporate healthcare systems – for example, special hospitals and sanatoriums for workers of the Ministry of Defense, or Ministry of Transportation, and so on. Also, there were special healthcare units for high-ranking Communist Party officials, which proves that public healthcare was far from ideal. Bribery and corruption were commonplace in Soviet hospitals – to have decent medical care, patients often had to bribe medics with money or expensive liquor.

A wedding in the builders' village of the Baikal-Amur mainline, 1974

Edgar Bryukhanenko/TASSThe famous phrase “There’s no sex in the USSR” was coined during a 1986 TV broadcast and hinted at the notion that highly politically conscious Soviet citizens had appropriately high moral standards, which didn’t involve sex as a pastime. Judging by classic Soviet movies, Soviet people only loved romantically, the way “true Communists” should.

READ MORE:What was wrong with life in the USSR?

However, even in the USSR, there were sex scandals, often involving high-profile officials and athletes. And at the very beginning of the communist system – before the USSR was a thing, there was even a brief, but incredibly vivid sexual revolution that drove a wedge between the old, Tsarist world, and the new one. In the 1960s, the hippie movement appeared in the USSR, with its ideals of sexual freedom. So, even though not officially acknowledged, sexual life in the USSR existed not only as a means to produce children, but also as a pastime.

On the other hand, contraception barely existed – condoms weren’t readily available even in most drugstores. Also, male homosexuality was considered a criminal offense for most of the USSR’s existence, so, even in sexual life, Soviet people were being oppressed.

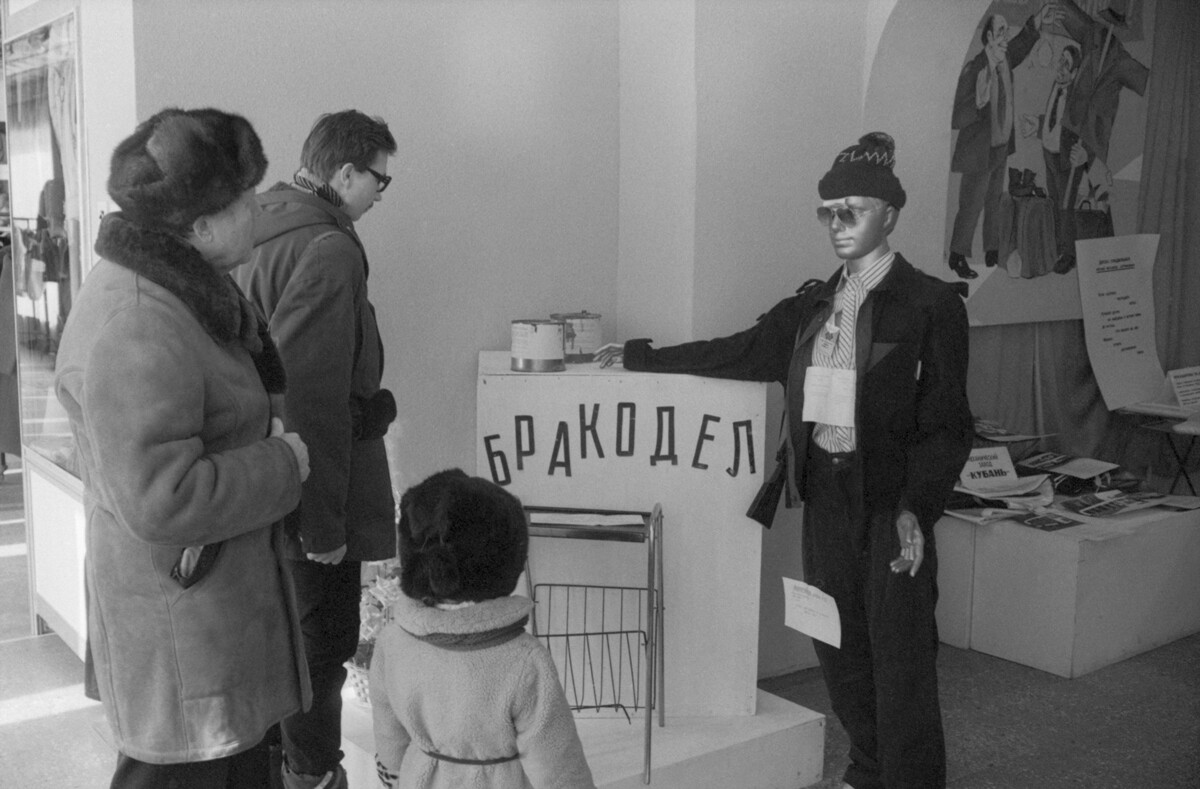

A mannequin labeled "Bungler", dressed in defective products of the Krasnodar Sewing Factory No. 2 and the Novorossiysk Kirov Factory as a part of the campaign to promote higher quality in labor, USSR, 1987

Vladimir Velengurin/TASS“Having survived the war, we were not afraid of starvation, and there was a certain confidence in the future,” Vera Ivanovna, a former head of the planning department at a Soviet aerospace company, said. However, although Soviet people didn’t starve (mostly), the goods they were offered by the state were of moderate quality. For example, in 1963, the State Trade Inspection found that 68 percent of all bicycles produced – as well as 34,7 percent of furniture – didn’t meet the quality standards. In 1965, senior party officials, including prime minister Alexey Kosygin, still discussed the necessity of state quality control for all produced goods.

Shortages were a common thing for Soviet people. “A shortage of basic cheeses, sausages, meat and ordinary chewing gum, and brightly-colored clothes and footwear for children, was a sensitive issue,” says Oleg, who spent his childhood in the USSR. While expensive and foreign items were easier to acquire in Moscow and St. Petersburg, most provincial cities and towns didn’t see quality goods until the fall of the USSR in 1991, which precipitated the rise in foreign trade and import.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox