On the evening of June 21st, 1941, Soviet border guards near the town of Sokal, Western Ukraine, apprehended a German defector, Alfred Liskow, who swam across the Bug river and surrendered. Liskow informed the boarded guards that, at dawn on June 22, the German army would attack the USSR.

Stalin was informed and “immediately agreed to put the troops on alert,” Marshal Georgy Zhukov later wrote in his memoirs. “Apparently, [he] had previously received such important information through other channels.” Only on the evening of June 21 was the Red Army and its air defenses finally put on alert. By then, all of the Wehrmacht’s attack forces were already in position to cross the border.

On The Russian Front

Interim Archives/Getty ImagesTo make matters worse, some army staff received the orders only in the morning, when the German onslaught had already begun. “Before dawn on June 22, wired communication with the troops was disrupted in all western border districts, and the headquarters of the districts and armies were unable to quickly transmit their orders,” historian Vladimir Karpov wrote. “German sabotage groups, which were already on our territory, destroyed the wire connection.”

However, the unit commanders who requested permission to open fire in the event of German troops crossing the border, were instead told to “not succumb to provocations." This was Stalin’s personal order. The Soviet troops had to retreat, and only at 7:15 in the morning, three hours after the German attack had started, were the Soviets allowed to retaliate. Such a catastrophic delay occurred because, until the very last moment, Stalin considered the attack a “provocation”.

Russian Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov with German Minister Von Ribbentrop and Josef Stalin.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesNazi Germany started preparing the attack on the USSR in mid-1940. All preparations were carried out in strict secrecy, lest Soviet intelligence catch wind of anything. The Germans were bombing English cities and preparing the fleet for crossing the La Manche strait, while at the same time regrouping their forces in Eastern Europe. On September 6, 1940, Alfred Jodl, the Chief of the Operations Staff of the German Army, sent orders for the disinformation of the Soviet leaders that plainly stated: “In the coming weeks, the concentration of troops in the East will increase significantly. From these regroupings of ours, Russia should by no means have the impression that we are preparing an offensive to the East.”

At the same time, Hitler tried to convince Stalin that Germany would follow the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, which ensured peace between the USSR and Germany. Hitler and other high-ranking Nazi commanders wanted to create the impression that Germany will attack England first. Hitler even mailed Stalin seeking military support against the British Empire, and Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov was even invited to Berlin for negotiations with Hitler and Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister. After the negotiations, Molotov was fully certain that England would become Germany’s first target. Meanwhile, in December 1940, Hitler signed ‘Directive No. 21 (Operation Barbarossa)’ on preparations for war against the Soviet Union. Itstated: "The German armed forces must be ready to defeat Soviet Russia during a short-term campaign even before the war against England is over."

26th November 1942: Armed with light machine guns, Soviet troops attack the German forces in the vicinity of the Red October plant in Stalingrad.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesHighest German commanders were, of course, aware of the plans, as they added to the conspiracy with their actions, historian Vladimir Lota writes. Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch, in a Christmas speech on the radio in December, claimed that "the Wehrmacht has only one task: to defeat England." However, starting from February 1941, German forces were being actively deployed in Eastern Europe. At the same time, their government had continued to discuss possibilities for economic cooperation with the USSR. However, Soviet foreign intelligence continued to provide facts that hinted at the possibility of an impending German attack. iIt was a pity Stalin didn’t believe them.

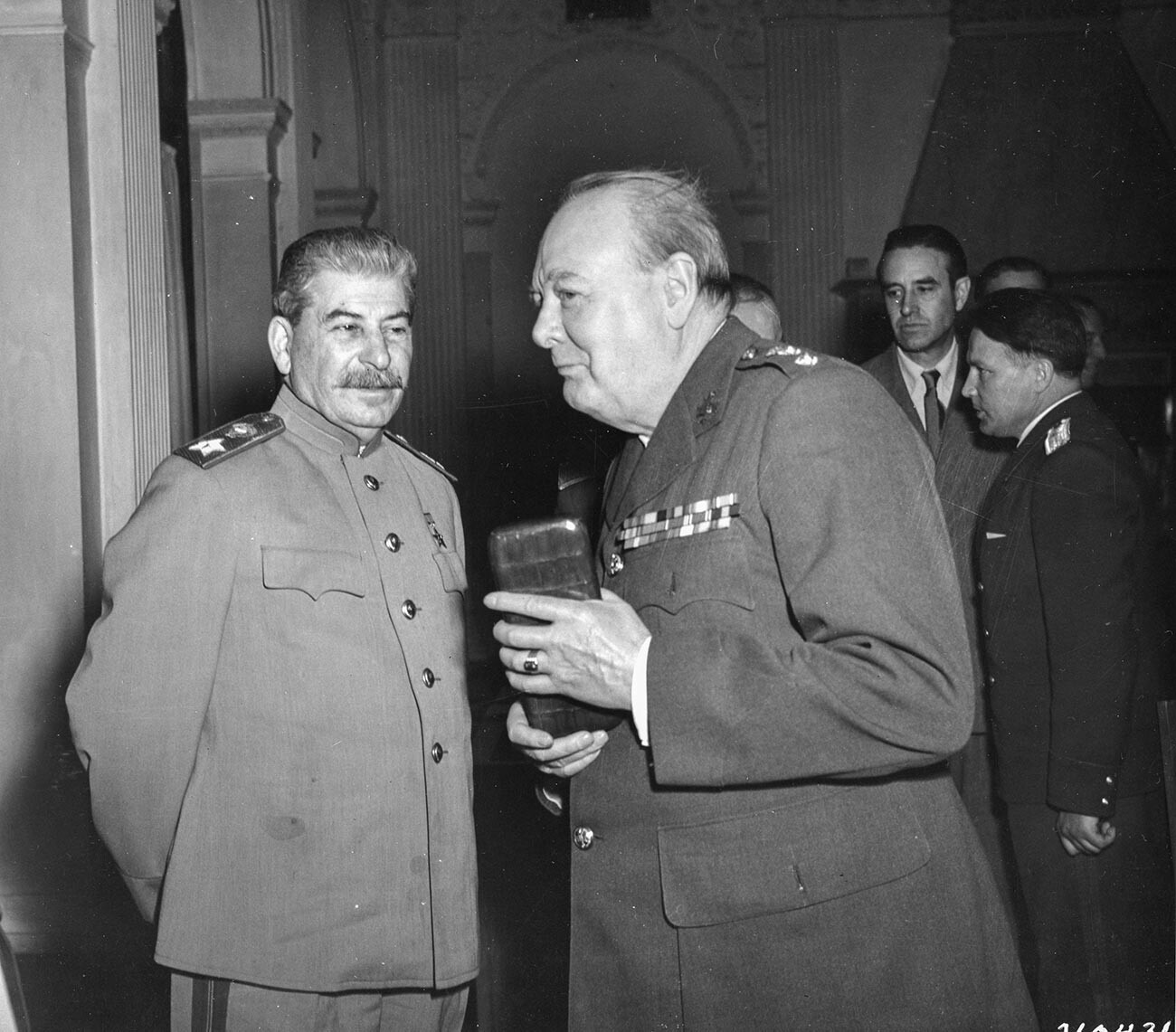

Stalin and Churchill at the Yalta Conference, held 4–11 February 1945

PhotoQuest/Getty ImagesJoseph Stalin didn’t trust Winston Churchill, who organized a campaign in the British cabinet for the severance of diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1927. Now that he was back in power, Stalin believed that Churchill was probably hatching a new anti-Soviet conspiracy.

As early as June, 1940, Winston Churchill sent Stalin a personal message that warned about Germany’s increasing hegemony over Europe. Stalin, however, considered it to be an attempt to divide the USSR and Germany. A year later, Churchill repeated his warning, now backed by solid intelligence, but to no avail. As Stafford Cripps, the UK’s ambassador to the USSR, remembered, “Stalin didn't want to have anything to do with Churchill, and most of all he was afraid that Germany would find out about his correspondence with Churchill.”

Warnings were coming from other sources as well. On April 17, 1941, an intelligence resident in Prague sent a warning to Moscow that Germany was going to attack the Soviet Union in the second half of June. His report was based on information received from a high-ranking German officer in Czechoslovakia, whose cover was that of chief engineer at the Skoda plants. The source had already earned full trust, but this proved insufficient: when the report was handed over to Stalin, he simply returned it with a sharp response, scribbled in red pencil: "English provocation. Sort it out! Stalin."

However, Stalin wasn’t naive, and understood that war was inevitable. The question was, how soon. The USSR still needed some time to finish its military preparations, and it certainly would have been more convenient if Hitler didn’t attack until 1942 at least. Among the intelligence reports that were coming in 1940 and 1941, many dates were indicated as the beginning of the war, but nothing happened. Mobilizing a nearly four-million-strong army was a serious decision, and Stalin couldn’t just believe every report, so opted to wait.

When Germany attacked the USSR, Stalin was apparently shocked beyond comprehension. He spent the first eight hours of the war trying in vain to prevent the "provocation" from escalating. He bombarded the German Foreign Ministry with radio messages – and even sought help from Japan, urging it to act as mediator to end the "crisis." Meanwhile, German troops invading Soviet territory seized all railways and bridges in the directions of the main offensive, raided 46 Soviet airfields, destroying about 1,000 Red Army aircraft on the ground, and also began a rapid advance inland on a 930-mile-wide front. Stalin’s miscalculation wasn’t fatal, it would turn out - but it sure cost the USSR and its people a lot.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox