When Anna Petrovna, Peter the Great’s second daughter, was born, she was considered to be an illegitimate child – her mother, Martha Skavronskaya (the future Catherine I) and her father weren’t married. After 1712, when Peter and Catherine were married, their daughters Anna and Elizaveta became tsarevnas, which meant little girls had palaces and lands given to them.

Anna in 1716. In the portrait, Anna is about six or seven years old, but her hair is done in an adult way and she is dressed like an grown-up lady

Ivan Nikitin/Tretyakov GalleryAnna and Elizaveta were brought up in a contemporary way, with special stress on foreign languages and highbrow manners. Already at the age of 12, the girls took part in court ceremonies and could support a formal conversation in French. It was Peter’s intention, to strengthen the ties between Russia and Europe, to marry his daughters to European princes and kings.

Unlike her sister Elizaveta, who would remain single for life, Anna indeed married a European prince, albeit a very poor one. Her husband, Charles Frederick, was the Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp – a small duchy, about 9,000 sq. km, on the border between contemporary Germany and Denmark.

Portrait of Charles Frederick of Holstein-Gottorp

David von KrafftCharles Frederick actually came to St. Petersburg in 1720, because the lands of his duchy were subjugated by king Frederick IV of Denmark, who declared himself the ruler of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp and made Charles Frederick seek help in Russia.

Peter the Great subtly refused to provide military help. Charles Frederick was by birth the grandson of Swedish king Charles XII, Peter’s archenemy whom the Russian tsar defeated in the Great Northern War (1700-1721). However, Peter allowed Charles Frederick to stay in Russia and even decorated him with the Order of St. Andrew, Russia’s greatest honor. St. Petersburg, Charles Frederick fell in love with the tsar’s daughter Anna.

Anna Petrovna and Elizaveta Petrovna, daughters of Peter the Great, circa 1717

Louis CaravaqueShortly before his death, Peter granted his consent for the marriage. In November 1724, a marriage contract was signed. Anna Petrovna retained the Orthodox faith and could bring up her daughters in Orthodoxy, while the sons had to be brought up in the father’s faith. Anna and her husband were denied the opportunity to claim the Russian throne, but the contract had a secret article, according to which, if a son would be born from this marriage, he would have the rights to the Russian throne.

Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna. Painting by Ivan Adolsky, circa 1740

Ivan Adolsky/HermitageWhen Charles Frederick and Anna Petrovna were married in June 1725, it was already after Peter the Great’s death. While Anna’s mother Catherine became Empress Catherine I, her husband Duke Charles Frederick occupied an important position as one of only 7 members of the Supreme Privy Council – it actually was Russia’s government that ruled the country instead of the Empress, who spent all her days mourning her late husband Peter.

In the Supreme Privy Council, Charles Frederick really affected Russia’s politics. But, in 1727, after Catherine’s death, Alexander Menshikov, the Chairman of the Privy Council, ousted Charles Frederick and Anna from Russia. They went to Schleswig-Holstein, where, in February 1728, in the town of Kiel, Anna gave birth to a boy named Charles Peter Ulrich – future Russian Emperor Peter III.

Charles Frederick of Holstein-Gottorp in his later years

David von KrafftShortly after childbirth, Anna Petrovna died. However, the circumstances of her death are unclear. The legend, told by scientist Jacob von Stäehlin in his memoirs, goes like this. Anna Petrovna, who had barely recovered from childbirth, went to the open window wanting to get a better look at the colorful fireworks celebrating her son’s birth. The damp and cold Baltic air rushed into the room, but Anna, flaunting her Russian origin, declared that she was not afraid of the cold. However, Anna Petrovna caught a cold and died of fever at the age of 20.

But, the problem is, Jacob von Stäehlin came to Russia in 1735 and he was probably retelling somebody else’s legend. Because Anna’s letters show she died in May 1728, three months after childbirth. Could she have been poisoned? Or was it the consequences of childbed fever, very common indeed in those days? We’ll probably never know. Her husband Charles Frederick was tasked with bringing up their son until 1739, when he died.

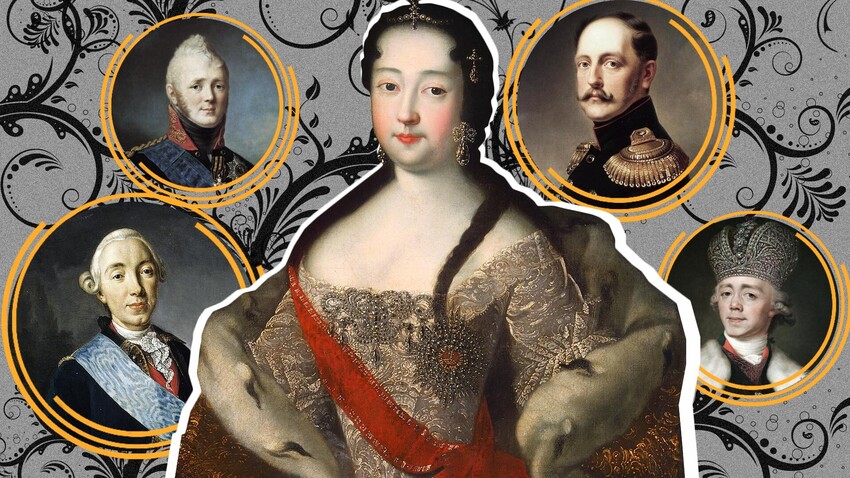

Peter III and Catherine II of Russia

Anna Rosina LisiewskaIn 1741, the 13-year old son of Charles Frederick and Anna Petrovna, Duke Charles Peter Ulrich, went to Russia. Elizabeth Petrovna, Anna’s sister, became the Russian Empress – and she wanted her sister’s son and her nephew to inherit the Russian throne.

As we know, Charles Peter Ulrich became Peter III, an unlucky Russian Emperor who was overthrown by his wife Catherine II and later murdered. Peter III was the first Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp to take the Russian throne and is considered the founder of the House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov. His son, Paul of Russia, and his wife Empress Maria Feodorovna had four sons and six daughters – this is why they had a really vast genealogical tree of descendants that included British royal persons.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox