“In my childhood, in the 1970-1980s, I went to visit my grandmother every year during the summer holidays. And, every time, my parents gave me strict instructions. They explained that I should never tell anyone where I was from. And if someone suddenly started asking questions about such things, I was supposed to interrupt the conversation and get away as soon as I could. Both my birth certificate and passport say that I was born in Chelyabinsk,” recalls Nadezhda Kutepova in her book ‘The Secrets of Closed Cities’. In fact, she was born in Ozyorsk, the “nuclear” town in the Urals which has been closed since Soviet times.

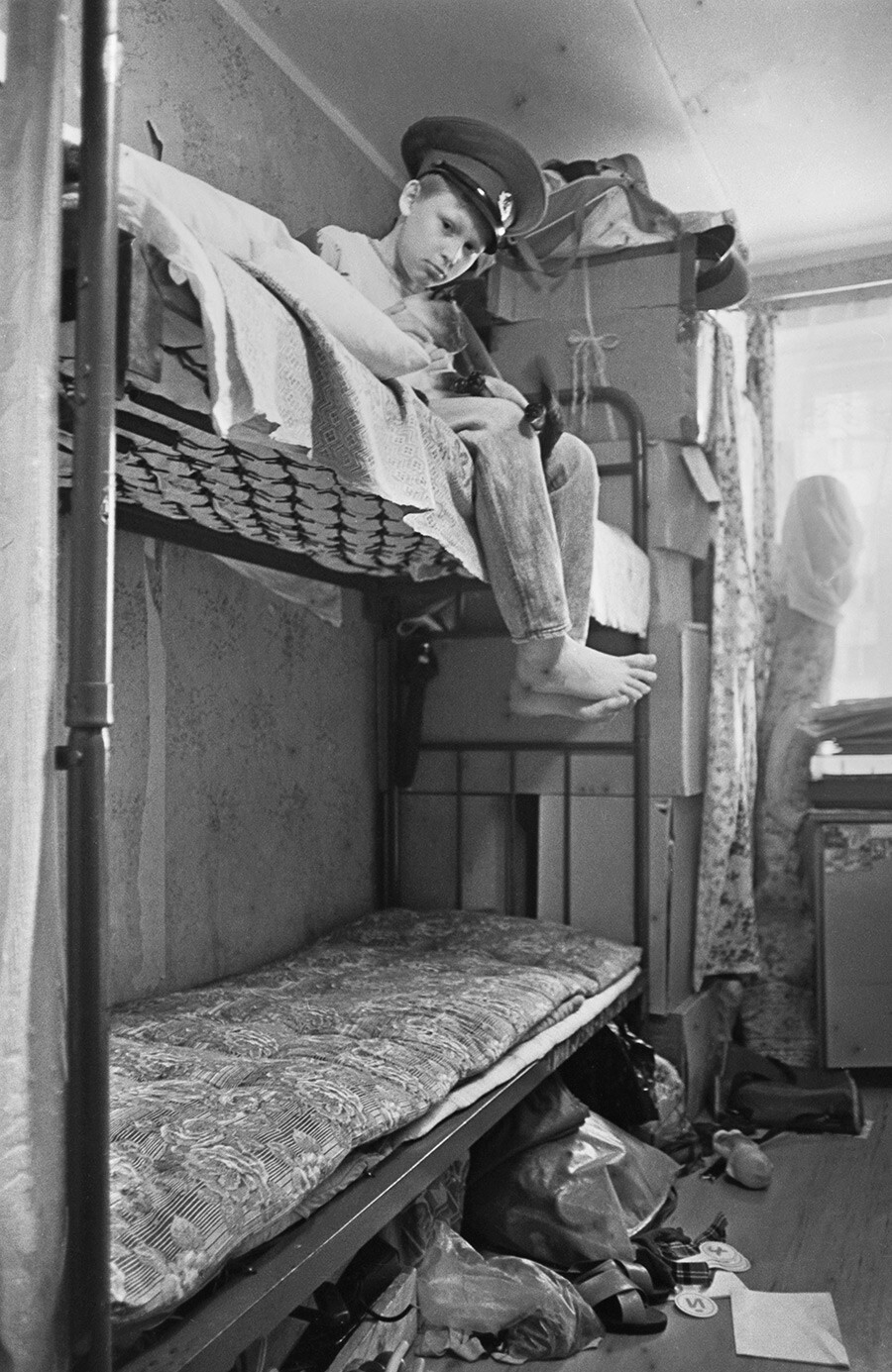

Arzamas-16, 1991.

Nikolai Moshkov/TASSClosed centers of population began to appear in the USSR after the launch of the nuclear program (between 1945-1953). Everything to do with the project was first classified as a military secret and then as a state secret. Even the names of radioactive substances were encrypted: It was prohibited to use the words ‘plutonium’ or ‘uranium’.

Publicly disclosed geographical names for these towns were established only in 1954. In allocating the names, the following principle was applied: “The name of the nearest center of population plus the number of the post office branch”; and these names were constantly changed. For instance, until 1994, the town of Sarov in Nizhny Novgorod Region had been known as Gorky-130, Arzamas-75 and Arzamas-16.

Even after 1954, the identity documents of their residents - builders, employees of nuclear industry enterprises and members of their families - showed not their actual place of residence but the nearest regional center. The residents had to sign a non-disclosure agreement.

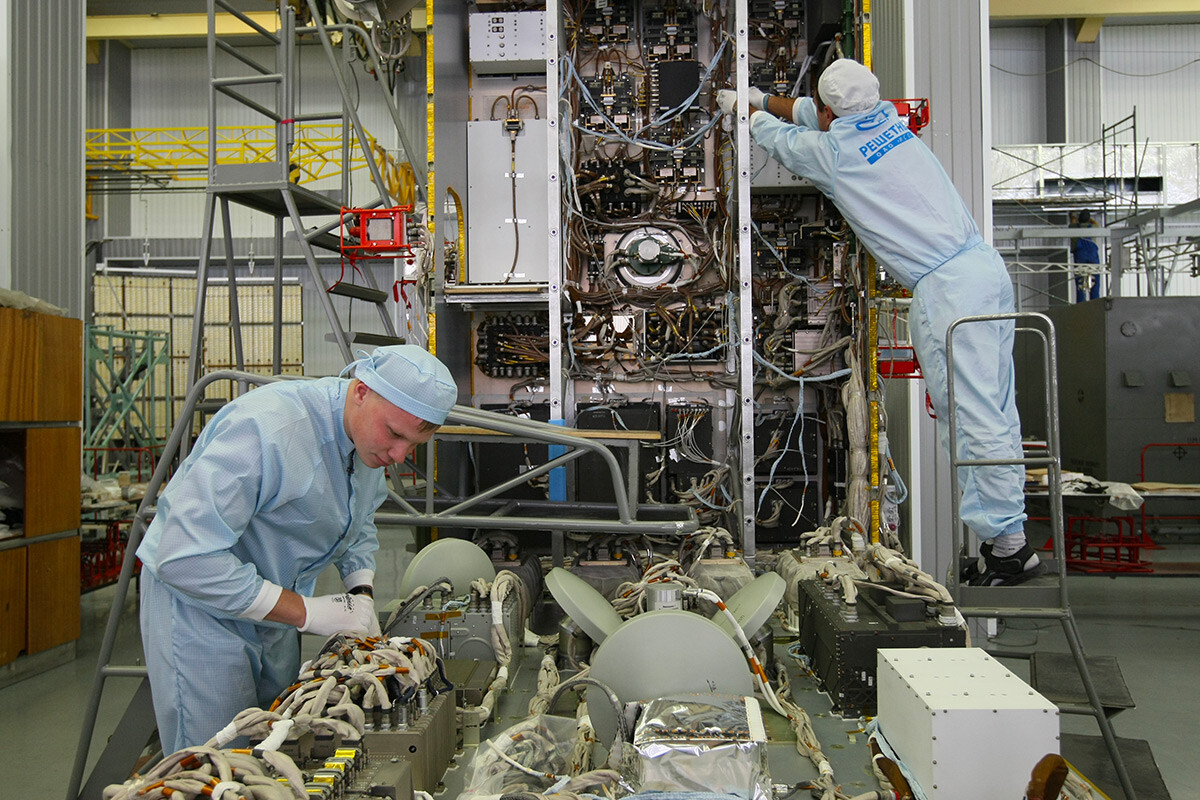

Krasnoyarsk-26 (now Zheleznogorsk).

Andrei Solomonov/SputnikThe first settlements were built near nuclear industry plants that were under construction. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, special requirements were applied to the sites of new plants and factories. For example, closed towns were predominantly located far from land borders and the European part of the country (to reduce the likelihood of an attack from the air), near a major water source and in places that were safe in terms of seismic, geological and hydrological factors.

Sarov, believed to have been founded in 1706, was an exception. The Monastery of the Holy Dormition, which became widely known thanks to its Father Superior, Saint Seraphim of Sarov, was established there at the beginning of the 18th century.

After the 1917 Revolution, the monastery was shut down and its buildings housed a children’s labor commune (detention center), a prison colony and then a physics laboratory.

Subsequently, closed towns, like nuclear enterprises, began to appear in the European part of the USSR, too. They also started being set up beside military installations throughout the country.

Arzamas-16.

Roman Yarovitsin/TASSInitially, travel outside the town limits by employees working at the town’s enterprises was not allowed and specialists had their passports taken away. Permission to leave town was granted in exceptional circumstances, such as the death of a close relative, the need for urgent or specialized medical treatment or a natural disaster. In every such case, documents had to be submitted confirming the necessity of travel, indicating the proposed route and including a pledge of secrecy. A cover story would be concocted for use by travelers once they passed the town’s exit checkpoints.

The rules were relaxed in 1954 when permission to leave the “zone” began to be granted without excessive bureaucracy. In 1957, long-term passes were introduced for residents. At first, travel outside the town limits was allowed once a week, but, for failure to return on time, the pass could be withdrawn for three months.

The entrance to Zheleznogorsk.

Andrei Solomonov/SputnikApart from significant restrictions, residents also enjoyed certain advantages:

Entrance to Seversk, 2010.

XioNoX (CC BY-SA)“My family decided to move to Krasnoyarsk-26 when Dad was offered a job there and Mom was pregnant. In the USSR in the perestroika era, food was in short supply and there were enormous waiting lines, but, in this closed town, the shelves were overflowing,” a closed city resident recalls in a YouTube interview.

Zheleznogorsk.

Alexander Kryazhev/SputnikAfter the collapse of the Soviet Union, the list of closed towns was declassified. Since 1992, the list has been kept under regular review and some of the towns have been gradually “opened up”.

Today, Russia has 38 closed administrative-territorial entities (figures as of January 1, 2021). Ten of them - the oldest closed towns, as mentioned above - are home to nuclear industry facilities, three of them host aerospace industry enterprises and another 23 come under the Ministry of Defence. One of them is the location of a laser test range, while another is the site of an enterprise for the construction of complex underground installations.

To enter any of these population centers, even Russians are required to apply for a permit and state the reasons for their visit. These could include having a close relative living locally, a business trip or work contract or attending public events, such as conferences or competitions. If sufficient reason cannot be provided, entry is likely to be refused.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox