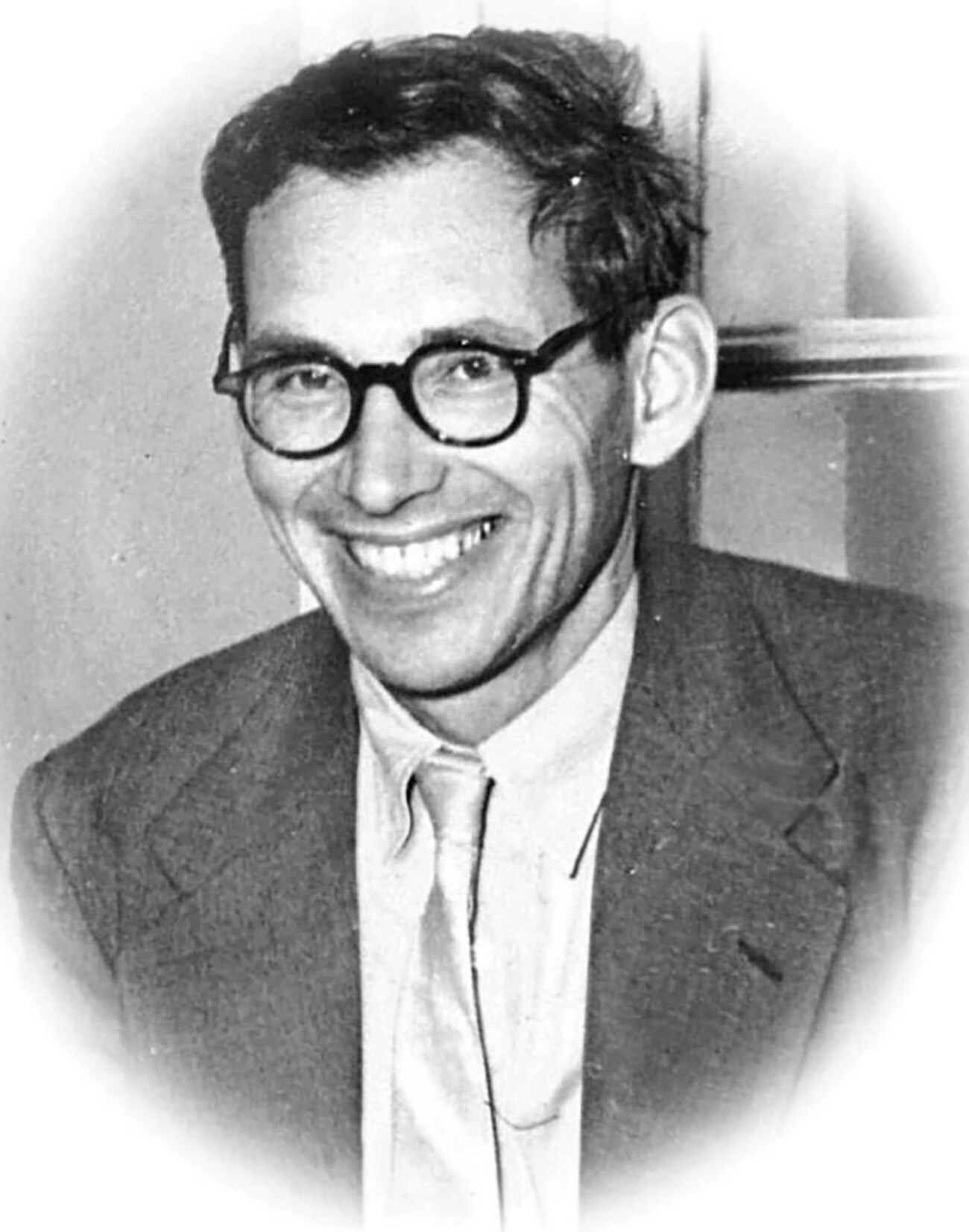

He was the most effective Soviet agent seeking to unearth the nuclear secrets of the Western powers. Klaus Fuchs was uniquely placed to acquire a thorough knowledge of not only the British, but also American, nuclear programs.

Being an ethnic German, Fuchs fled Germany after Hitler came to power in 1933. He settled in Britain, where he studied to become a physicist. Another German refugee named Rudolf Peierls recruited the talented specialist for his group working on the development of atomic weapons under the ‘Tube Alloys’ program.

It was Klaus himself who approached Soviet intelligence and offered his collaboration shortly after Germany attacked the Soviet Union. The scientist was annoyed that the British were doing little to help the Russians and that their research into weapons of mass destruction was being kept secret from their allies.

“He was a dedicated communist,” American physicist Victor Weisskopf said about Fuchs. “He believed that the atomic bomb should not belong only to the Western world… Equilibrium must exist.” The scientist categorically refused to take money for his intelligence activities.

In 1943, Fuchs, together with a number of other British physicists, joined the ‘Manhattan Project’, America’s nuclear program. This gave Moscow access to the secrets of its overseas ally and rival, including the calculations, dimensions and drawings relating to the first atomic bombs. This information helped Soviet scientists to reduce the time it took to develop their own nuclear weapons by several years.

In 1949, the agent was exposed and sentenced by the British to 14 years in prison. The Americans sought his extradition to the U.S., where he would have faced the death penalty, but London refused. Klaus Fuchs was released early in 1959. Stripped of his British citizenship, he settled in the GDR where he devoted the rest of his life exclusively to science.

George Koval, born in the U.S. in 1913 into a family of Russian immigrants, was no less valuable to the Soviet Union as a provider of nuclear secrets. When he was 19, his family returned to their historical homeland to flee the Great Depression.

In 1940, Koval found himself back in North America - this time as an agent of the Soviet secret services. His initial task was to seek out information on the development of chemical weapons, but, soon, his sphere of activity changed.

In 1943, George was called up into the U.S. Army. And since, prior to his departure for the USSR, he had managed to study for two years in a technical college, he was sent to serve at a radioactive material production plant. After undergoing the relevant training, the spy ended up at a secret installation in the city of Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Koval closely studied the particularities of the technological cycle of uranium and plutonium production, which he then reported in detail to Moscow. Thanks to its agent, the Soviet Union also learned about the location of a number of secret atomic facilities in the U.S., their internal structure and operating principles.

George Koval was later transferred to a laboratory in the city of Dayton, Ohio, where he observed the final stage of work to develop an atomic weapon. The information passed on by the spy helped Soviet scientists to overcome problems related to the production of their own bomb, tests of which took place already in 1949.

George returned to the Soviet Union that same year. He did so in the nick of time, too, as the FBI had already begun to take a detailed interest in his activities. In the USSR, Koval quit the spying game and devoted himself entirely to scientific work.

Born in Bournemouth in southern England, Melita Norwood was interested in socialist ideas from a youthful age. By 1932, when she was hired as a secretary at the British Non-Ferrous Metals Research Association, she was already a zealous communist.

If the management of the association had known of Melita’s political views, it would never have offered her a job, since the organization was closely linked to the secret development of nuclear weapons. Soviet intelligence, for its part, discovered the young woman’s devotion to the ideas of “world revolution” and could not miss the chance to acquire a valuable agent.

Norwood was recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1937 and collaborated with them for the next 35 years. Because she supplied Moscow with copies of highly important documents relating to the ‘Tube Alloys’ program, Stalin was better informed of the British nuclear program than some members of the British Cabinet.

Like Fuchs, Melita Norwood refused to be paid for her work (but happily accepted the award of the Order of the Labor Red Banner). “I did what I did not to make money, but to help prevent the defeat of a new system which had at great cost given ordinary people food and fares which they could afford, good education and a health service.”

On two occasions, in 1945 and 1965, MI5, the British counterintelligence service, had suspicions about Norwood’s true identity, but, on each occasion, they lacked adequate proof. In 1972, she quietly retired, thus concluding her intelligence-gathering activities.

It was only in 1992, after an enormous number of files of Soviet agents was divulged by a defector, that the truth about Melita came out. It was decided, however, not to prosecute the then already 80-year-old “granny spy”, as the press had dubbed her.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox