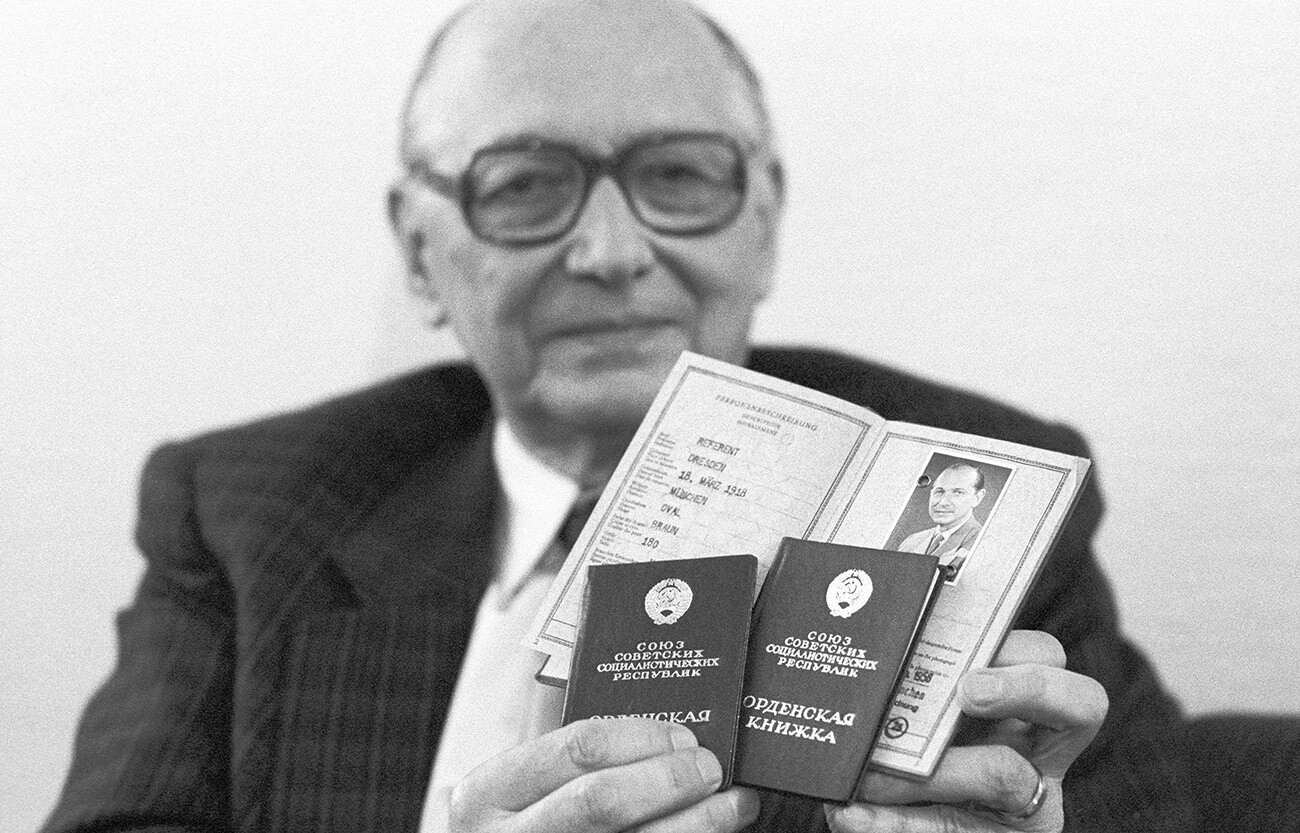

Heinz Felfe giving an interview on the occasion of the presentation of his autobiography in East-Berlin.

Mehner/ullstein bild via Getty Images“I was convinced that Hitler had finally given the German people what they needed in the troubled time of the Weimar Republic: a clear purpose, strict order and discipline… I saw the National Socialist Movement as a force that could lead Germany towards a new economic and political flowering.” So reasoned SS-Obersturmführer Heinz Felfe, an intelligence officer of the Third Reich, in his youth.

He couldn’t have imagined then that, in a short space of time, he would be transformed from an ardent Nazi into a convinced communist and take an entirely different view of the Soviet people, whom he once considered subhuman.

Adolf Hitler with Nazi party Hitler Youth.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesFelfe had joined the Nazis in 1931 when still a teenager. After several years in the Hitler Youth organization, he enlisted in the SS.

“We, SS employees, felt we were the elite of the nation and, as such, were called upon to fulfill the grandiose destiny of the leading role of the German nation, in which we firmly believed. We could feel no other way,” Heinz argued.

Hard work, perseverance and outstanding organizational skills, as well as a higher degree in law, allowed Felfe to make a brilliant career in Office VI (Foreign Intelligence) of the Reich Security Main Office (German abbreviation: RSHA). In 1943, at the age of only 25, he was appointed head of the department responsible for Switzerland and Liechtenstein. Moreover, his subordinates included people above him in rank.

Just before the collapse of the Third Reich, Obersturmführer Felfe tried to leave the ranks of the SS, which was already firmly associated with war crimes, and obtain a transfer to the Wehrmacht, but failed. In May 1945, he was captured by the British and spent a year and a half in detention.

Heinz Felfe during World War II.

Archive photoIn 1946, Heinz Felfe was released after his involvement in war crimes could not be established. Subsequently, he collaborated for a while with MI6, the UK’s Secret Intelligence Service, to uncover underground communist groups at the University of Cologne.

In the early postwar years, Felfe actively re-examined the events of the past and his role in them and thought a great deal about the path he should take in the future. Living in West Germany, he frequently visited the Soviet occupation zone, including his native Dresden, where his mother still lived.

“Standing before the ruins of my home town, I regarded it as symbolic that Anglo-American bombers had pointlessly destroyed Dresden, while, after May 8, 1945, Soviet soldiers had supplied and distributed food to Berliners,” Heinz wrote in his memoirs. “It was clear to me that a new - in other words, peaceful and democratic - Germany could only be built by means of loyal and friendly cooperation with the Soviet Union, that the future of Germany lay only in the East and that I wanted to make my contribution to this.”

Destroyed Dresden.

Fred Ramage/Keystone Features/Getty ImagesIt comes as no surprise, therefore, that when, in 1951, the USSR special services made contact with Felfe, he willingly agreed to cooperate with them. “I was surprised by the high level of trust placed in me by the Soviet side,” Heinz recalled. “After all, I had been a serviceman in the SS and had worked for fascist intelligence. When, much later, I asked about this, I was told: ‘Why does it surprise you? We knew about your past life. And we realized that you and we would be able to see eye to eye.’”

Felfe was then involved in refugee matters as an employee of the Federal Ministry of All-German Affairs. On Moscow’s instructions, he joined the Gehlen Organization, an intelligence service that had recently been established in West Germany. Named after its chief, Reinhard Gehlen, a former lieutenant-general of the Wehrmacht, the organization was under the control of the CIA and actively recruited former Third Reich intelligence agents to its ranks. “The ‘old soldiers’ were in demand again,” Heinz noted.

In Gehlen’s organization, which, in 1956, was reorganized into the Federal Intelligence Service, the BND, Felfe rose rapidly to become chief of the department of counter espionage against the USSR and socialist countries. In effect, he was supposed to conduct operations against those for whom he was actually working.

Heinz Felfe giving an interview on the occasion of the presentation of his autobiography in East-Berlin. Felfe showing his German passport and ID cards form the USSR.

Mehner/ullstein bild via Getty Images“As a result of my counterespionage work in the BND, I could supply Soviet intelligence with information about the service's intentions,” Heinz recalled. “We identified dangerous actions by the BND in good time and, holding the position that I did, I helped to ensure active measures to counter them.”

This was how Moscow learned that listening equipment had been planted in the Soviet trade mission in Cologne and also about attempts to recruit the mission’s staff. Felfe sent warnings of planned arrests of Soviet intelligence operatives in West Germany, allowing them to go into hiding in time.

What is more, Felfe also received information about the activities of the West German government and about state policy on foreign affairs and matters concerning relations with NATO. “The documents that the BND would send to [Konrad] Adenauer (FRG federal chancellor 1949-63) were frequently already in Moscow before they had landed on his desk,” according to Soviet special services operative Vitaly Korotkov.

Thanks to the work of Heinz Felfe and his agents, between 1951 and 1961, the USSR got its hands on more than 15,000 photocopies of secret documents and established the names of 94 West German spies operating in socialist bloc countries.

Heinz Felfe on the way to the court building on 8 July 1963.

Fritz Fischer/picture alliance via Getty ImagesThroughout this 10-year period, Soviet intelligence in the FRG did not suffer a single major failure and, ultimately, this could not but arouse the suspicions of BND chiefs. Gehlen ordered a special group to be set up inside the organization to hunt down the “mole”. It ultimately carried out its remit successfully.

On November 6, 1961, Heinz Felfe was arrested. He refused to cooperate and was sentenced to 14 years in prison. According to the judgment, “he posed a high degree of danger above all by virtue of his important official position, his high intellectual capacity and complete absence of conscience”.

On February 17, 1969, Felfe was exchanged for 21 GDR prisoners suspected of espionage. After working for a time in the KGB in Moscow, the spy settled in Berlin, where he was involved in criminalistics and writing his memoirs.

The Soviet Union honored Heinz Felfe with the orders of the Red Banner and Red Star. On March 18, 2008, not long before his death, the spy received 90th birthday greetings from the Russian Federal Security Service.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox