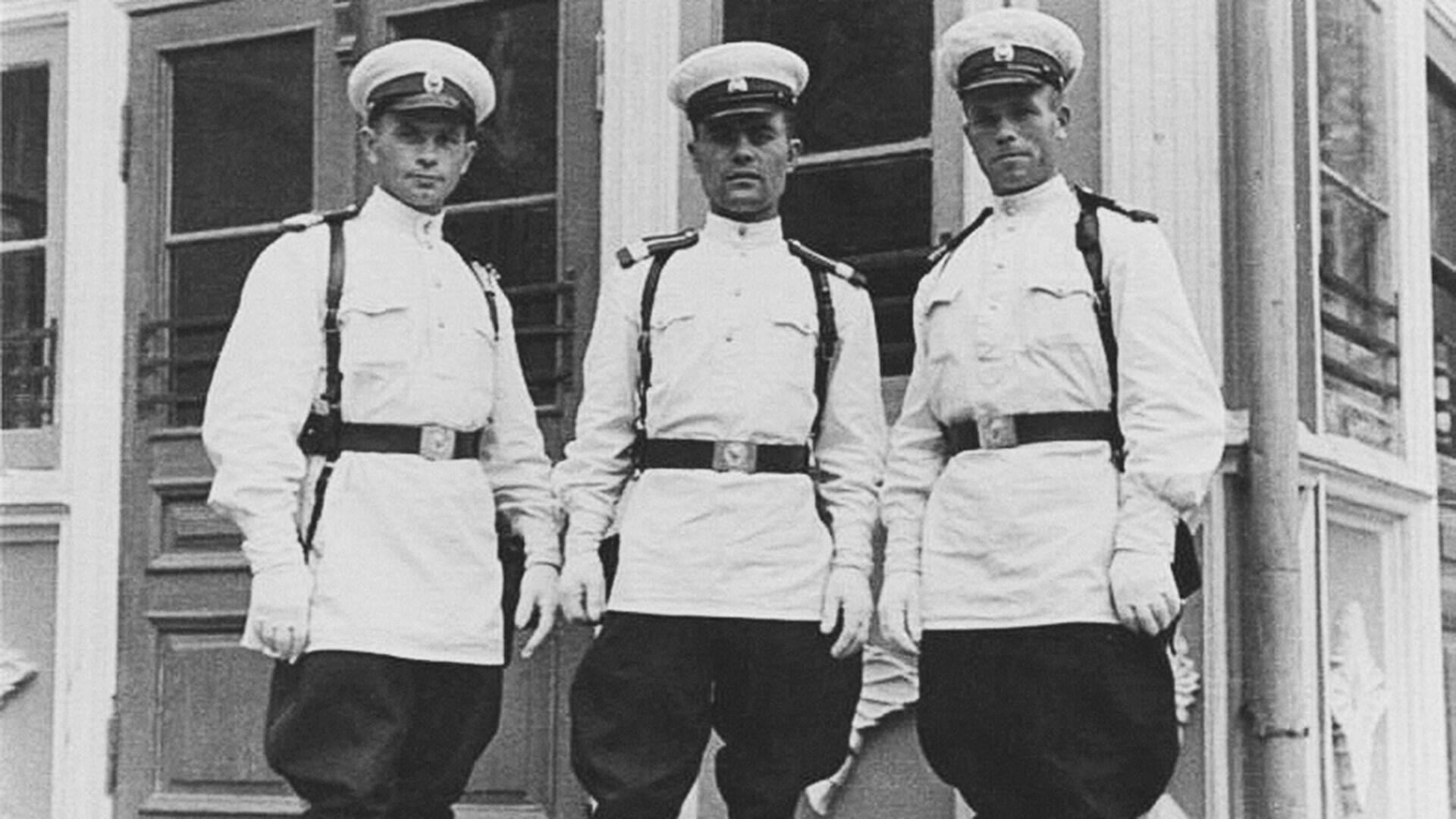

Soviet policemen.

Archive photoFrom the start of the Wehrmacht’s invasion of the USSR, Soviet police had their work cut out for them, as they faced many difficult and crucial new tasks. The latter included tracking down German sabotage and reconnaissance groups inside the front lines, capturing deserters and draft dodgers, cracking down on looters and countering the spread of panic in society.

Members of the law enforcement bodies couldn’t neglect their immediate duties, either. The involvement of the country in a terrible war led to a sharp rise in crime in cities and villages and those had to be dealt with, too.

Soviet policeman.

russiainphoto.ruAt the same time, many policemen were mobilized into the Red Army or volunteered for the front. They were also recruited en masse into the NKVD (The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) troops - the Soviet police were part of the NKVD structure. These interior troops were engaged in guarding the borders, rear areas, railways, industrial enterprises of special importance and places of detention; and, sometimes, they became directly engaged in combat operations, too.

But, the police did not always fight the enemy as part of large military formations with the benefit of military training and with proper weapons at their disposal. At times, these custodians of law and order had to go and fight the Wehrmacht’s experienced soldiers straight from their desks, armed only with a pistol, a rifle and a Molotov cocktail.

Brest police department before the war.

Archive photoHeroic resistance to the German army was put up in the first hours of the war by members of the transport police department at Brest railway station in the border town of that name. Under the command of department chief Senior Lt. Andrei Vorobyov were not just members of the police, but also disparate groups from the 17th Brest border detachment and the 60th rifle regiment of USSR NKVD troops charged with guarding railway infrastructure.

“The place was crowded with people, shells were bursting and there were fires all around,” recalled a policeman named Nikita Yaroshik. “Panic started among the passengers. Vorobyov gave the order for the priority evacuation of women and children. He sent some of the men to the platform to keep order during the dispatch of the train. The train was the last one that managed to get out. Vorobyev ordered a group of policemen to collect all the personal and confiscated weapons and ammunition and to take up defensive positions at the Zapadny Bridge.”

Senior Lt. Andrei Vorobyov.

Archive photoThe policemen repelled several enemy attacks before they were pushed back to the station. The Nazis rapidly managed to completely besiege the building. The defenders were forced to shelter in the basement from where, short of food, water and ammunition, they fought on for two more days.

Eventually, it was decided to attempt a break-out from the station building, which was by now engulfed in flames. On June 25, the fighters broke the encirclement and escaped from the trap with significant losses. Vorobyov immediately headed back to his family in the now enemy-occupied town, but his landlord immediately reported his appearance to the Gestapo. The policeman was seized and, after interrogation, shot.

Representatives of senior Moscow police officers at the military firing range.

Archive photoFor six days, from July 13 to 18, 1941, a composite police battalion numbering 250 men under the command of Lt. Konstantin Vladimirov defended the northern approaches to the city of Mogilev in eastern Byelorussia.

The makeshift sub-unit was poorly armed and a significant proportion of its members were cadets from the Minsk and Grodno police academies. In spite of this, the men fought to the bitter end.

“The police battalion repelled six attacks by superior enemy forces supported by artillery and mortar fire and aviation,” Vladimirov reported to his command on July 17. “We have killed up to 400 Hitlerite soldiers and officers. Our losses: 118 soldiers, sergeants and mid-ranking commanders have fallen and half the men still in action are wounded. In the seventh attack, the enemy seized Staroye Pashkovo. I plan a counter-attack with all available forces to recover the situation. Ammunition is running low. I’ll hold out for 10-12 hours.”

Lt. Konstantin Vladimirov.

Archive photoInfuriated by the resistance the policemen had put up, the Germans prohibited people from neighboring villages from touching the fighters in navy blue uniform that lay all around. They had to bury the dead clandestinely at night.

Members of the interior affairs bodies took part in the defense of Riga, Tallinn, Lvov, Kiev, Dnepropetrovsk and many other cities alongside regular troops. In fighting near Kingisepp in August-September 1941, a battalion of the Narva Workers’ Regiment, formed entirely from members of the Estonian police, was almost completely wiped out.

For nine months, from the end of October 1941 to July 1942, when Sevastopol was besieged by the German army, members of the city police worked to track down and eliminate enemy sabotage groups and artillery spotters and to combat banditry and looting. Withdrawing to Cape Khersones alongside the remnants of the garrison in the last days of the defense of the city, they took part in street fighting themselves. Captain Vasily Buzin, the city's chief of police, was killed in this action.

Soviet police in 1942.

Archive photoThis is how marshal Vasily Chuikov, who played a crucial role in the defense of Stalingrad, viewed the role of the men of the law enforcement bodies in those events: “As a participant in that unprecedented historic battle, I would like to stress the courage, fortitude, tenacity and self-possession of members of the Stalingrad police in the defense of the city. Under ceaseless bombing raids and artillery and mortar fire, they escorted people out of the city and evacuated them to the other side of the Volga, put out fires, protected the valuables and property of citizens and maintained public order. It would be difficult to overstate their role in helping the troops arriving to assist the defenders of the city to make the river crossing… At critical moments when the enemy managed to drive a wedge into our defenses somewhere, members of the police stood in the line of fire a good many times…”

The number of killed and missing members of the interior affairs bodies and NKVD troops during the whole period of the war against Nazi Germany and its allies is estimated at 159,000.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox