Today a citizen of the Russian Federation can’t be deprived of citizenship. This principle is enshrined in the law on citizenship and in Article 6 of the Russian Constitution. But in the Soviet Union, forced abrogation of citizenship was a form of political repression against dissenters. Here are the most famous cases.

Leon Trotsky

Legion MediaOne of the Bolshevik founders of the Soviet Union, Leon Trotsky fought a political struggle with Stalin in the mid-1920s and lost. In 1927, he was expelled from the Communist Party, and in 1928 he was exiled to Alma-Ata, (today, Almaty, which is the capital of Kazakhstan). Trotsky was given an unofficial ultimatum from Stalin – to lie low and completely cease all political activity. When Trotsky refused, the government decided to expel him from the country.

In February 1929, Trotsky, his wife and their son, accompanied by state security officers, were taken to Istanbul. On February 20, 1932, the newspaper Pravda published the decision of the Presidium of the Chief Executive Committee of the USSR signed by its chairman, Mikhail Kalinin, which announced the abrogation of Soviet citizenship for Trotsky and his family "for counterrevolutionary activities". We have a separate article on his fate.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn coming back to Russia, 1994

D. Korotaev/SputnikOriginally a loyal and dedicated communist, Alexander Solzhenitsyn decided to become a writer in his youth, just shortly before World War 2, when he enrolled in the literature department of an institute in Moscow. When the war began, Solzhenitsyn was eager to enlist and go to the front. In the army he began to be critical of Stalin's policies as head of state, which he recounted in letters to a friend. These letters became the reason for his arrest and imprisonment – 8 years in the gulag and three years in exile. In 1957, he was rehabilitated.

Solzhenitsyn’s experience in the gulag became the basis of his "camp prose", which under Khrushchev was allowed to be published in the USSR. However, when Brezhnev came to power in 1964, Solzhenitsyn’s writings were again banned. Nevertheless, he began an active social life in dissident circles, promoting himself and his writing. While his works weren’t accepted by the Soviet authorities, they managed to circulate secretly among the intelligentsia as samizdat. In 1970, Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize. Despite constant KGB surveillance and poisoning attempts, Solzhenitsyn declined the state’s offer to leave the USSR.

In early 1974, the highest ruling Soviet authorities discussed Solzhenitsyn’s fate and decided to deprive him of citizenship and deport him from the country, which took place on February 12, 1974. Soon after, the writer and his family left the country, and published copies of Solzhenitsyn's works began to be destroyed. Only in 1990 was his Soviet citizenship reinstated in 1990, and in 1994 he returned to Russia. He died in 2008 in Moscow.

Viktor Korchnoi

Fred Grinberg/SputnikThe eminent chess player Viktor Korchnoi was in conflict with the Soviet system in large part because of his impulsive youthful character, about which he wrote in detail in his book Anti-Chess. Korchnoi won numerous Soviet national championships and he was one of the finest chess players ever in history. In 1966, Korchnoi said that Soviet authorities proposed he give up his citizenship, but he refused. "I lost 11 years of a good life," Korchnoi later regretted.

In 1974, Korchnoi lost to Anatoly Karpov in a candidate match against world champion Bobby Fischer. The match took place in Moscow, and Karpov enjoyed the obvious support of the "bosses". Suffice it to say that paid clappers were sitting in the hall, and they applauded Karpov profusely but greeted Korchnoi with icy silence. This was unsurprising, taking into account the strict hierarchy of Soviet sport and Karpov's loyalty to the authorities.

READ MORE: How Russian chess players used psychic powers against each other

After the match, Korchnoi sharply criticized both Karpov and the Soviet Sports Committee, and he did so publicly in the Yugoslavian press! The chess player then faced disciplinary measures and was banned from traveling outside the USSR for a year.

Jewish Soviet citizens near the Consulate of Israel in Moscow, USSR

Oleg Lastochkin/SputnikAt the first opportunity, however, when the ban was lifted, Korchnoi set off for a tournament in the Netherlands, and there he requested political asylum. He was eventually granted asylum in Switzerland, living the rest of his life there.

In 1978, he was stripped of his Soviet citizenship with the statement – "taking into account that V. L. Korchnoi systematically committed acts incompatible with his citizenship of the USSR, and by his conduct damaged the prestige of the USSR." Although Korchnoi, along with many other "non-returnees" and dissidents, were given back citizenship in 1990, he refused to return to Russia officially as a citizen. However, he did participate in a few chess tournaments in Russia.

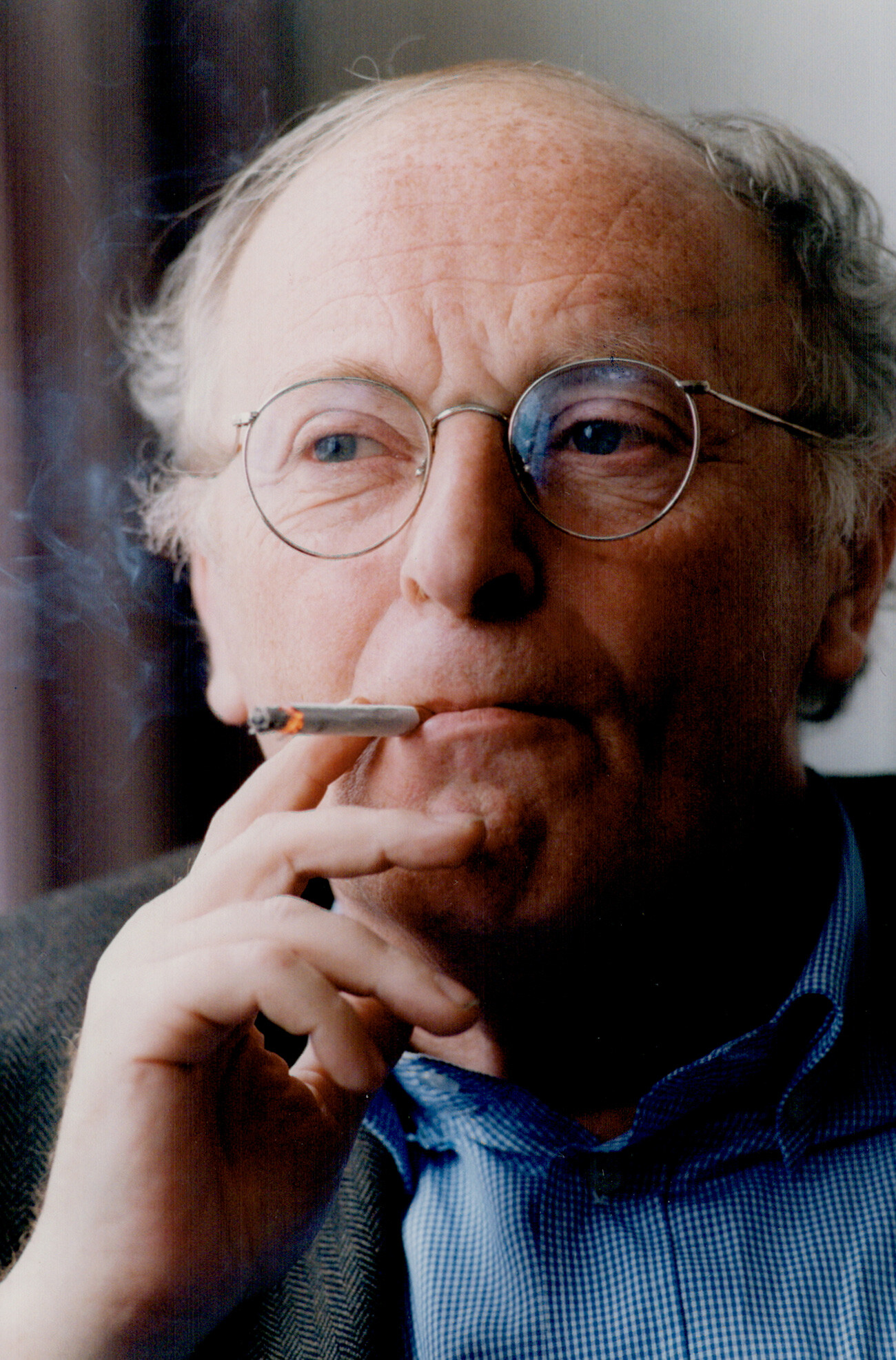

Joseph Brodsky

Keith Beaty/Toronto Star/Getty ImagesJoseph Brodsky, the second Nobel Prize winner on our list, was stripped of his Soviet citizenship in 1972. We have a detailed article about that.

Emigrants from USSR in Tel-Aviv airport

Alexander Yerokhin/TASSIn 1921, the Council of People's Commissars passed a decree – "On abrogation of citizenship rights of certain categories of persons living abroad.” According to the decree, citizenship of the RSFSR was stripped from all those who previously had citizenship of the Russian Empire, and stayed abroad more than 5 years, and did not apply to the Soviet missions for documents; as well as all those who served in foreign armies or the police. In 1928, at the suggestion of a number of Soviet embassies, 16 people in different countries were deprived of citizenship "for anti-Soviet activities.”

Starting 1938, according to the "Law on Citizenship of the USSR," abrogation of citizenship was possible by a court decision or even by the decision of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. In 1958, this issue was removed from judicial jurisdiction and thus became a purely political punishment.

Emigrants in line to the US Embassy in the USSR

Alexander Nemenov/TASSREAD MORE: Was emigration from the USSR even possible?

Article 18 of the new Law on Citizenship of the USSR (1978) stipulated that citizens could be deprived of their citizenship for "actions that denigrate the high rank of a citizen of the USSR and damage the prestige or national security of the country. As researcher Elena Ponizova writes, "such a formulation opened the door to the arbitrariness of state agencies and officials in assessing the behavior of citizens.

During all the years of Soviet rule, dozens of dissidents and those who disagreed with state policies were deprived of Soviet citizenship, as were many writers, philosophers, directors, and other people of creative professions. The reason was often the same – the inconsistency of their work with the general ideological line of the CPSU. Most often, those who had already gone abroad were stripped of their citizenship, including by blocking any chance of their return and even destroying their families.

During Perestroika, many of these repressive citizenship measures were finally reversed. On August 15, 1990, President Mikhail Gorbachev signed the decree – On Cancellation of the Decrees of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on Deprivation of Citizenship of the USSR of Some Persons Residing Abroad. This decree returned citizenship to almost all persons who faced such politically-motivated persecution during the period 1966-1988.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox