«Boyarinya near a window», Konstantin Makovsky, 1884

Mikhail Vrubel Omsk MuseumCheeks smeared with beet juice, huge black eyebrows and a kokoshnik – this image of the “Russian beauty” dominated Soviet fairytale movies. The image is both true and false, at the same time.

The kokoshnik, a northern wedding headdress, became widespread only from the late 18th century in Moscow Russia, so the image of Russian women in kokoshniks in the pre-Petrine times is a myth. Besides, only peasant women would smear their cheeks with beet and berry juice. Noble women used more expensive, but no less colorful cosmetics.

"Wedding procession in Moscow in the 17th century," by Andrey Ryabushkin, 1901

Tretyakov galleryWe know about Russian cosmetics in the 16th-17th centuries from the writings of foreigners, who were blown away by the beauty of Russian women – and, at the same time, by how much makeup they put on their faces.

“The women’s faces are so beautiful that they surpass many nations,” Swedish diplomat Hans Moritz Ayrmann wrote of the Russians in 1669. “The women in Muscovy have a slender stature and a beautiful face, but their innate beauty is distorted by excessive ‘rouge’,” echoed another European named Jacob Reutenfels in the 1670s. “Their faces are round, their lips protrude forward and eyebrows are always painted and the whole face is painted, for they all use makeup. The custom of wearing it is considered, by tradition, so necessary, that a woman who does not want to paint her face is considered arrogant and seeking to distinguish herself before others, having the audacity to consider herself beautiful enough and dressy even without paint and artificial embellishments,” Reutenfels added.

And there was, indeed, such a case – it was recorded by Adam Olearius, who visited Moscow even earlier, in the 1630s. “The nobleman and boyar Prince Ivan Borisovich Cherkassky’s wife had a very beautiful face and did not want to wear makeup, at first. However, the wives of other boyars pestered her, saying she treated the customs and habits of their own country with contempt and disgraced other women with her way of behaving. With the help of their husbands, they made this naturally beautiful woman wear white face paint, ‘rouge’ and, so to speak, light a candle on a clear sunny day.” Ivan Cherkassky was the second person in the state after the tsar, the head of the government of the country. And even his wife was not allowed by other noble ladies to neglect makeup.

"Moscow girl of the 17th century," by Andrey Ryabushkin, 1903

Russian MuseumForeigners noted that Russian women were very brightly colored. “The ‘rouge’ used by them is so coarse that there is no need to be close up not to notice it,” Reutenfels wrote. “They so smear their faces that one can see the colors pasted on their faces almost at a shot’s distance; it is best to compare them with the wives of millers, for they look as if sacks of flour had been pounded near their faces,” Anthony Jenkinson, an English diplomat of the 16th century, wrote.

Nevertheless, the cosmetics did their work. British poet George Turberville, who visited Moscow in the 16th century, wrote of a Russian noblewoman:

“She decks herself, and dyes her tawny skin, she pranks and paints her smoky face, both brows, lips, cheeks, and chin. <…> But such as skilfull are and cunning dames indeed, by daily practice do it well, yes sure they do exceed: they lay their colors so, as he, that is full wise, may easily be deceived therein, if he does trust his eyes.”

"Noble Russian women at a church service," by Andrey Ryabushkin. Note how pale the woman on the right is – she is probably using white lead.

Tretyakov gallery‘Rouge’ and other products were very bright, because they were based on toxic chemicals. Russians did not know then that their cosmetics were not just harmful to health, but also deadly. But, let’s remember that even at the feasts of the highest nobility, the lighting was very dim, so women had to use noticeable, contrasting colors. In the light of day, faces with such cosmetics seemed caricatured.

The face was whitened with white lead: “In cities, women’s faces seem as if sprinkled with flour and ‘rouge’ was as if smeared on the cheeks with a rough brush,” wrote a Dutchman Balthazar Coyett, who lived in Moscow in 1675-1676. White lead has been known since antiquity, even Roman historian Pliny the Elder (AD 23/24 – AD 79) reported that this paint was obtained by “the action of the sharpest vinegar on the smallest lead scrapings”.

White lead evenly covered the skin and gave the purest white color. But, Russian women were unaware that the lead carbonate which they were putting on the skin poisoned the body. “Fever, stomach aches that did not go away for two or three weeks, nausea and insomnia were explained either by stale food or the evil eye, spoilage from unkind people. But, in reality, it was a ‘lead colic’ from the metal accumulated in the body,” writes historian Marina Bogdanova.

Baroque style Venetian mirror. Italy, late 17th-early 18th century. Such mirrors were used by the Russian noble beauties of the era.

DeAgostini/Getty Images“They look like owls,” the Czech traveler Jiří David wrote about Russian women who had huge black eyebrows. The component used to blacken eyelashes and eyebrows by mixing it with fat and oil was stibnite powder commonly called ‘kohl’, a compound of lead and sulfur that also harmed the skin and made it dark – just like white lead. English merchant Giles Fletcher noted “a dark, sickly complexion of the skin” in Muscovite women – the cause of which he believed to be long periods of confinement in winter. However, Fletcher socialized with women of the highest Moscow circles, so we can assume that their skin was dark from the constant use of whitewash. Remember how Turberville wrote of “her tawny skin” and “her smoky face”? He was probably referring to the same thing.

READ MORE: The strangest 'medicine' Russian peasants used

The ‘rouge’ on cheeks, the brightness of which was noted by all foreigners, was certainly not made with juice. They included cinnabar, a mercury sulfide. These days, chemists are recommended to work with cinnabar “in a fume cupboard, with rubber gloves, goggles and a gas mask on”, due to its vapors being toxic. And, back then, it was applied to the face and hair as a brightly colored dye. Mercury chloride, or ‘sulema’, was used in creams to soften the skin.

Cinnabar powder

AliexpressMercury is one of the strongest neurotoxins, regular inhalation of its vapors leads to neural trauma. And Russian women whitened their teeth with mercury. On the background of bright white lead, any teeth looked yellow. In addition, noble women liked to indulge in sugar and candy, the most expensive treats in Russia – which caused tooth decay. Therefore, for example, before the wedding, one could whiten one’s teeth with mercury. Six months after such a procedure, the tooth enamel would begin to fall off. And that’s why teeth were blackened with coal soot – it was necessary to do it all the time. Alexander Radishchev noted that, in the provinces, in merchant families, this method of hiding bad teeth persisted until the end of the 18th century: “Paraskovya Denisovna, his newlywed wife, is white and ruddy. Her teeth are like coal. Eyebrows in a string, blacker than soot,” he recorded in 1790.

"A tsarevna visiting a cloister," 1912, by Vasiliy Surikov

Tretyakov galleryIn their quest for beauty, Russian women even went so far as to eat “white arsenic” (arsenic trioxide). It acted as a drug – increased appetite, mood, efficiency, eyes began to shine brightly. As it accumulated in the body, arsenic also slowly killed. Arsenic, lead and mercury were found in huge quantities in the remains of Russian tsarinas of the 16th century – for example, the wives of Ivan the Terrible.

Finally, a dye made of soot mixed in alcohol was put into the eyes. “The Russians know the secret of blackening the very whites of the eyes,” Samuel Collins, Alexei Mikhailovich’s court physician, remarked with amazement.

Many contemporaries realized that such cosmetics were harmful to health. Jacob Reutenfels concluded his description of Russian cosmetics harshly: “As retribution for fake beauty… approaching old age, [they] have faces that are riddled with wrinkles.”

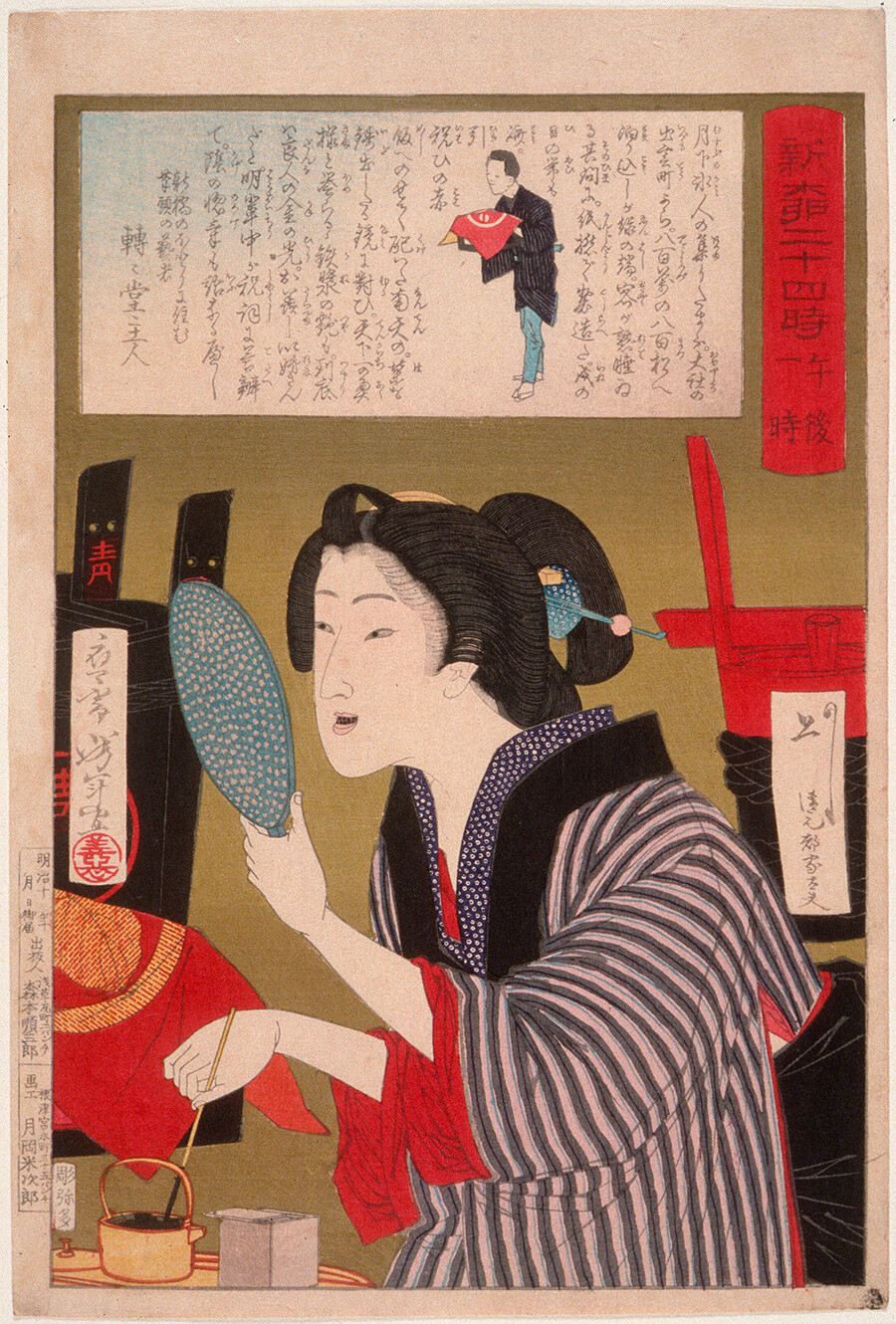

Geisha Blackening Teeth At 1:00 P.M. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), Japan, 1880

Legion MediaInterestingly, the blackening of teeth and the eyes, the lining of eyebrows with soot and the use of white lead were characteristic of the women of Mongolia and China. In the text ‘Meng-da bei-lu’ (‘Complete Description of the Mongolo-Tatars’, 1221), written by a Chinese traveler, we read: “Women (Mongols) often smear their foreheads with yellow whitewash. [This] is a borrowing of old Chinese cosmetics and still remains unchanged…” At the same time, in the descriptions of pre-Mongol Russia by foreigners, no mention of bright cosmetics could be found. It can be assumed, therefore, that these fashions were borrowed by Russian women from the Mongol-Tatar nobility, which once adopted them from the Chinese of the Tang era (7th-10th centuries).

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox