A man of unbridled courage, Scotsman Alexander Leslie was one of the most prominent mercenaries of the 17th century. He enlisted for Russian service three times: in 1618, 1630 and 1647.

During the siege of Polish Smolensk in 1633, a "foreign formation" regiment under his command saved the regiment of Thomas Sanderson, another mercenary colonel, from total defeat by Polish winged hussars. However, this did not prevent Sanderson from being later shot in cold blood by Leslie at a military council, accused of treason.

Alexander Leslie was not only a talented commander, but also a capable recruiter. Even before the outbreak of the Smolensk War, he managed to recruit more than four and a half thousand mercenaries for Russian service, enough to make up four “German” regiments.

The Scotsman's third visit to Russia almost cost him his life, however. Boyars, unhappy at foreign domination, accused him of spitting on the altar in an Orthodox church, firing a gun at a cross and forcing Russian servants to eat dog meat, while his wife was accused of burning icons in a stove.

But it was Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich (Alexis of Russia) who helped Alexander to avoid death. He invited his protégé and his officers to adopt Orthodoxy, to which they gladly accepted. In 1654, Leslie became the first man in Russian history to be awarded the rank of general.

In 1771, Jan Hendrik van Kinsbergen, a Dutch naval officer with 20 years of impeccable service and expeditions to the West Indies and the coast of North Africa under his belt, decided to go to distant Russia.

The country welcomed experienced sailors. Soon, Kinsbergen was put in command of a naval squadron and found himself in the thick of the Russo-Turkish war, in which he displayed his military talents to the full. The Dutchman boldly attacked the numerically superior enemy, often inflicting serious losses and forcing them to withdraw their ships.

“I have the honor of testifying that Captain and Knight Kinsbergen is an excellent and courageous naval officer, thoroughly worthy of advancement,” Rear Admiral Alexei Senyavin wrote in a document conferring an award on the officer.

In 1775, soon after the end of the war, the Dutchman left Russia, despite the fact that Empress Catherine the Great herself asked him to remain in Russian service. In the Netherlands, Jan Kinsbergen rose to the rank of admiral and even commanded the republic’s navy at one point.

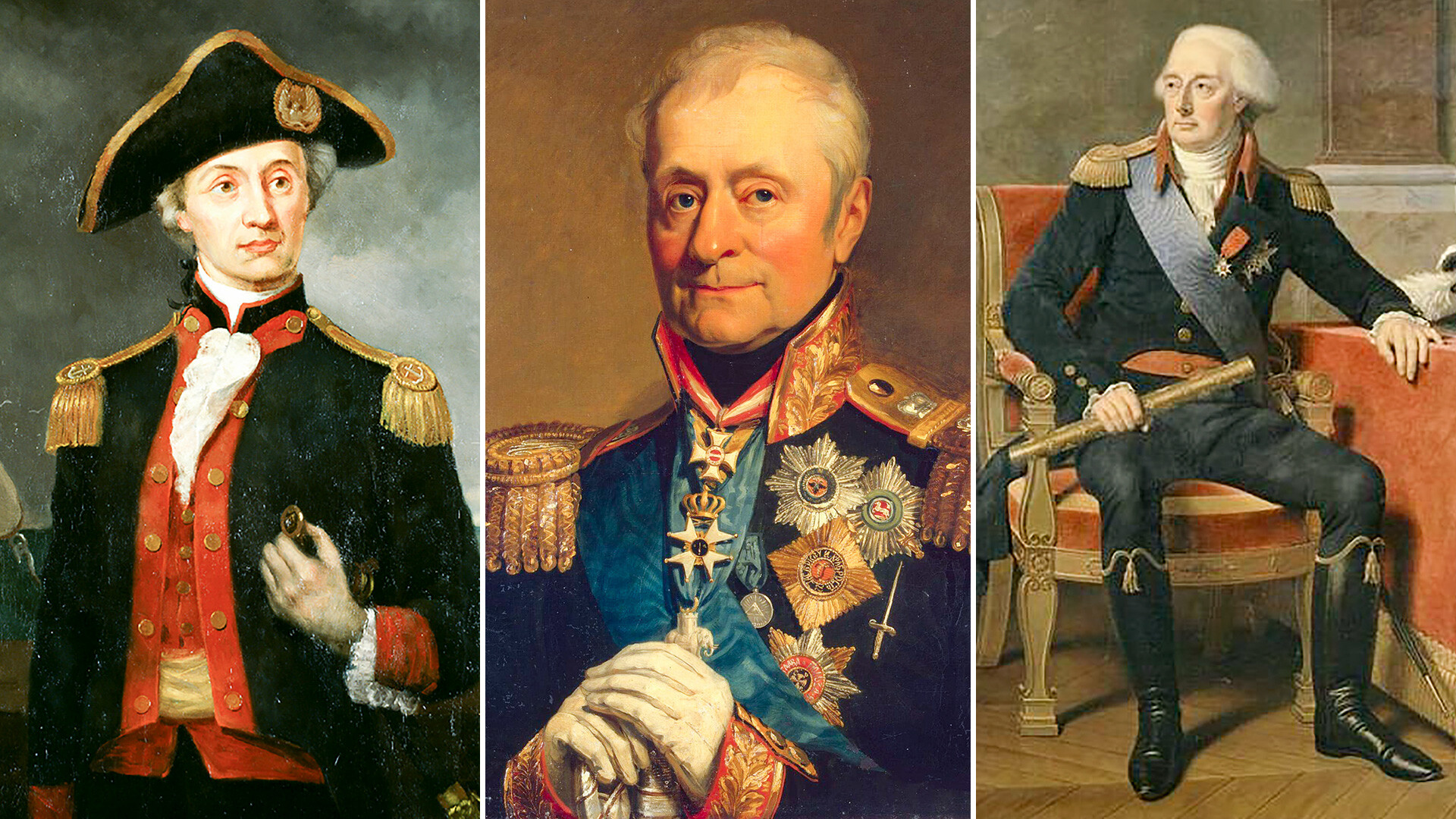

John Paul Jones was not only one of the first officers in the Continental Navy during the American War of Independence, but was also the most successful. He was responsible for one of the most resounding American naval victories in the conflict: the capture of the British sloop-of-war HMS Drake and the 50-gun frigate HMS Serapis.

After the end of the war in 1783, the "Father of the American Navy", as the naval commander is often called, found himself at a loose end. He spent four years languishing in diplomatic service in Europe before Empress Catherine II invited him to Russia.

Jones was immediately promoted to Rear Admiral (in the U.S. Navy, he had only risen to the rank of captain) and sent to the Black Sea, where he was placed under the command of His Serene Highness Grigory Potemkin. "This man is extremely capable of multiplying shock and awe in the foe," the empress wrote to Potemkin.

The American vindicated the trust the empress had placed in him. Commanding a squadron of 11 ships in June 1788, he, along with the Russian oared flotilla of Rear Admiral Karl Nassau-Siegen, defeated the Turkish fleet near the Black Sea fortress of Ochakov. The enemy lost 15 ships and 6,000 men; in addition, fifteen hundred were taken prisoner.

John Paul Johns was expecting to be appointed to the Baltic when he unexpectedly found himself at the center of a sex scandal: He was accused of raping a 10-year-old girl. Despite the fact that an investigation resulted in the charges being dropped, he was now persona non grata in Russia. In August 1789, the resentful and embittered naval captain left the country for good.

Before arriving in Russia in 1788, Gomes Freire de Andrade made a successful career in the Portuguese army and navy. Nevertheless, the officer dreamed of a major war, which his own country could not offer him at this time.

Russia was simultaneously conducting wars against the Ottoman Empire and Sweden, in which de Andrade managed to take part.

He was one of the first who, on December 17, 1788, scaled the walls of the fortress of Ochakov. In recognition, Empress Catherine II decorated him with the military order of the Cross of St. George 4th Class.

After this, he set off for the Baltic to fight against the Swedes. For his excellent command of a floating battery (a slow-moving ship with powerful artillery guns for besieging coastal fortresses) in the course of the First Battle of Svensksund, which took place on August 24, 1789, he was awarded the Gold Sword for Bravery and promoted to colonel.

In 1791, after the wars against the Turks and Swedes were over, Gomes Freire de Andrade returned home. Gomes found himself in Russia again in 1812, but, this time, the visit was not a friendly one. As an officer of the Portuguese Legion, he took part in the full-scale incursion into the territory of the Russian Empire by Napoleon’s Grande Armée.

He did not, however, take part in combat, as his duties involved acting as military governor of the town of Disna (today Dzisna in northern Belarus). In the winter of that year, he left Russia, together with the meager remnants of the French troops. This time for good.

Many Frenchmen did not accept the French Revolution of 1789 and fought in the ranks of foreign armies for the restoration of the monarchy. The most combat-effective of the émigré royalist formations was the corps of Louis Joseph de Bourbon, Prince of Condé.

For many years, de Bourbon’s soldiers fought shoulder to shoulder with the Austrians, but after the defeat of Austria and her withdrawal from the war in 1797 the prince was forced to find another sponsor.

That was when Russian emperor Paul I extended a helping hand to the royalists. By agreement with the exiled French King, Louis XVIII, he admitted the émigré corps into Russian service. The French were issued with a new uniform, as well as banners and standards that combined Russian and French heraldic symbols.

In the ranks of the Russian army, Condé’s royalists took part in the War of the Second Coalition against the French and regularly demonstrated courage and striking tenacity on the battlefield.

When, in 1800, Russia withdrew from the conflict, the corps went onto Britain's payroll. In gratitude for their loyal service, its soldiers were allowed to keep all their personal equipment, weapons, uniforms and even wheeled vehicles and horses.

Baron Levin August Gottlieb Theophil von Bennigsen entered Russian service in 1773 as a lieutenant-colonel in the army of Hanover. There, he distinguished himself in wars against the Poles, the Turks and the Persians and, for his bravery, he was awarded several decorations and a gold sword with diamonds, as well as large estates with serfs.

On February 7, 1807, near the town of Preussisch Eylau in East Prussia (now the town of Bagrationovsk in Russia’s Kaliningrad Region), the Russian army under Bennigsen’s command fought on equal terms against the troops of Napoleon himself. Neither side ultimately achieved a decisive victory but for Napoleon the battle was an unmistakable failure that shook the French soldiers’ faith in their invincible emperor.

The commander went on to fight against the French during the Patriotic War of 1812 and the Russian army’s foreign campaign of 1813-1814. Soon after hostilities ceased, he applied for retirement and returned to his native Hanover, where he spent the last years of his life.

Jaime de Borbón, Duke of Madrid and Anjou and claimant to the Spanish throne, was a very infrequent visitor to the Iberian Peninsula. This was because of the setbacks the Spanish Bourbons encountered in the struggle for power inside the country.

Duke Jaime lived and studied in various European countries until, in 1896, he found himself in Russia, where a dazzling military career awaited him. Rising to the rank of colonel, the Spaniard managed to serve in the Imperial Guard and to take part in the Eight-Nation Alliance's intervention in China in 1900 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905.

On the battlefield, the Spanish aristocrat was always to be found on the front lines, displaying irrepressible bravery. In one battle against the Japanese army, General Alexander Samsonov attempted to get the Duke to leave a dangerous sector of the battlefield, reminding him that his life was needed by Spain. "General, if I were a coward, I would not be worthy of my country!" Jaime de Borbón replied to him.

The Duke of Madrid and Anjou left Russian service in 1910, but he was never to become king. For the next 20 years, he continued wandering around the countries of Europe, periodically visiting Spain, prior to ending his days in Paris in 1931.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox