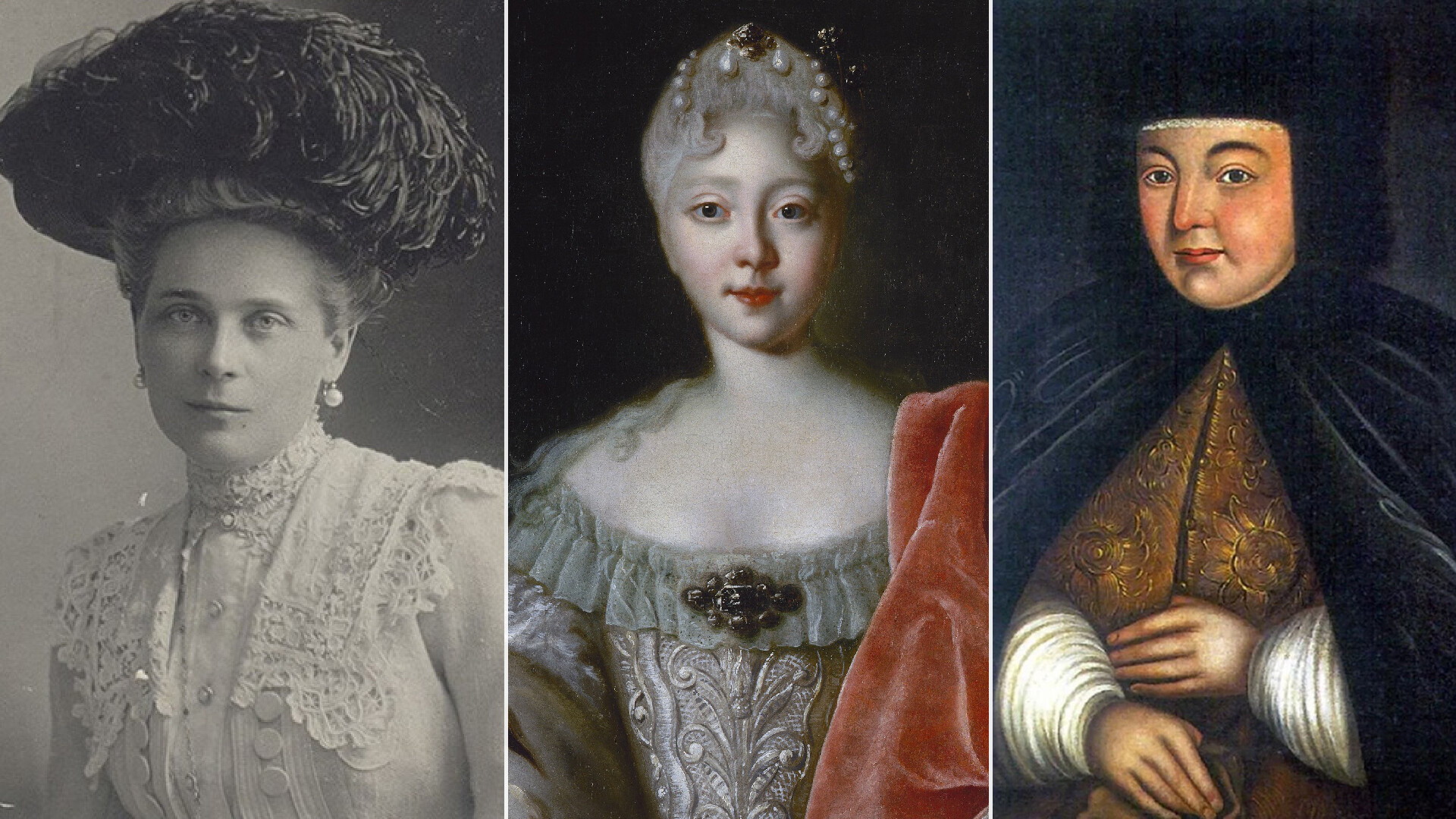

It’s hard for us to imagine what Russian beauties truly looked like in the distant past, because there was no means to capture their looks. Portraiture began developing in Russia only in the 17th century with the emergence of ‘parsunas’ (a transitional genre between a religious icon and a secular portrait). Paintings in their traditional understanding appeared only under Peter the Great. Russian portraitists and, later, photographers, left a tremendous amount of depictions of the muses of the past.

Natalya was a daughter of not-very-rich noble small landowners and, according to the customs of her time, couldn’t even dream of marrying a tsar. But, the girl was raised in the house of an influential boyar named Artamon Matveev – there, she met Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich. A few weeks after that, the ruler sent for Natalya and they married.

According to the recollections of Courland diplomat and traveler Jacob Reutenfels, this is what the tsaritsa looked like: “This is a woman in her most flourishing years, of a stately height, with black bulging eyes; she has a pleasant face, round mouth, high forehead, a graceful proportionality in all her limbs, her voice is sonorous and pleasant, she is of manners most gracious.”

Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, the daughter of Peter the Great, was famous for her incredible beauty in her youth. Spanish diplomat and military man James Stuart (Duke of Liria) remembered young Elizaveta as follows: “Princess Elizaveta, the daughter of Peter the Great and Tsaritsa Catherine, is a beauty I’ve never seen before. The color of her face is amazing, her eyes are fiery, she has a perfect mouth, the whitest of necks and an amazing stature. She’s tall and incredibly lively. She dances well and rides a horse without a shadow of fear. Her conversations demonstrate a lot of intellect and pleasantness, if only some vanity.”

“Who in Russia is not familiar with the name of Maria Antonovna? I remember as, during the first year of me being in St. Petersburg, I stood in front of her theater box, my mouth open in amazement and, in the silliest way, admired her beauty, so perfect that it seemed unnatural, impossible. I’ll say only one thing: in St. Petersburg, which, at the time, had a lot of beauties, she was way ahead of the rest,” memoirist Filipp Vigel wrote. He also writes in his memoirs about her love connection with Emperor Alexander I – for their contemporaries, their relationship wasn’t a secret.

A friend of Alexander Pushkin, poet Pyotr Vyazemsky remembered the princess the following way: “Black, expressive eyes, thick dark hair pouring down on her shoulders with waving locks, the southern tanned color of her face, a good-natured and gracious smile: add to it her voice, her incredibly soft and pleasant-sounding speech… her beauty, overall, echoed of something plastic, reminiscent of an ancient Greek statue. Nothing in her exposed any deliberate concern, everyday female deviousness or fussiness. On the contrary, there was something bright and calm in her, more like lazy, impassive.” Both Vyazemsky and Pushkin visited her salon and the latter, obviously, was in love with Avdotya. The poet dedicated three poems to the ‘princesse Nocturne’, as contemporaries called her for her late receptions.

The wife of Russian poet Alexander Pushkin enjoyed fame as the best beauty of St. Petersburg. A contemporary of Goncharova, Nadezhda Eropkina, wrote about her: “Nataly was distinguished for her rare beauty already as a teenage girl. She was taken out to society very early and she was always surrounded by a swarm of suitors and admirers. She also participated in charming tableau vivant, staged at Governor-General Prince Golitsyn’s place and evoked everyone’s admiration. The title of the ‘best beauty of Moscow’ was hers.

Natasha was truly beautiful and I have always admired her. From being raised in a village, in pure air, she inherited flourishing health. Strong, agile, she was incredibly proportionally built and, due to this, every movement of her was full with grace. She had kind, cheerful eyes, with a fervent fire under long, velvety eyelashes. But, the shroud of shy modesty has always timely stopped impulses too eager. The main delight of Natalya was the absence of any affectation and her naturalness. The majority thought her to be a coquette, but such an accusation is unrighteous.

Her incredibly expressive eyes, her charming smile and her attractive simplicity in approach conquered everyone for her against her will.”

The younger daughter of Alexander Pushkin and Natalya Goncharova was also an incredible beauty. That’s what the son of writer Mikhail Zagoskin, Sergey Zagoskin, said about her: “…In my whole life, I have not seen a woman more beautiful! It was Natalya Alexandrovna Dubelt, born Pushkina, the daughter of our immortalized poet. Tall, incredibly slender, with amazing shoulders and beautiful paleness of face, she shone with a sort of dazzling brilliance. Despite her somewhat irregular facial features, reminiscent of the African type of her famous father, she was able to enjoy being called the most perfect beauty and, adding intellect and good manners to this beauty, you can easily imagine how she was surrounded at balls and how all the flamboyant youth swarmed around her, while the old ones couldn’t keep their eyes off her…”

The first husband of Natalya, Mikhail Dubelt, was an avid card player. He lost not only all his fortune, but also the dowry from his wife’s family. After a tormenting divorce, Natalya managed to still find her happiness, marrying German aristocrat Nikolaus Wilhelm of Nassau.

The young woman in the portrait was “…considered not only a beauty of St. Petersburg, but also of Europe. Showing her brilliance on shores overseas, at seaside resorts, in Biarritz and Ostend, as well as at Tuileries, at the height of the mind-bending luxury of Empress Eugénie and the splendor of Napoleon III, V. D. Korsakova shared her successes between St. Petersburg’s high society and the French court, where people nicknamed her ‘Venus’,” as her acquaintance, Prince Dmitry Obolensky wrote about her.

The beauty was the epicenter of scandals many times. One of them occurred in 1863 – she appeared at a ball in a semi-transparent attire of gauze. According to legend, for this insolence, she was escorted out by policemen.

The heiress of one of the wealthiest families of the Russian Empire was also the most eligible bachelorette in St. Petersburg. Even members of European royal families sought her hand in marriage, but she wished to pick a husband according to her tastes – and married a regular officer, who had accompanied one of her failed suitors.

Eulalia de Bourbon, a Spanish infanta, who visited the Yusupovs, said this about the princess: “The princess was astonishingly beautiful, with the beauty that is a symbol of the era. She lived among paintings and sculptures, in a luxurious Byzantine style… At lunch, the hostess sat in her gala dress, decorated with diamonds and marvelous eastern pearls. She was stately, flexible; on her head, she wore a kokoshnik – or a diadem, as it is also known. Also studded with pearls and diamonds, this headdress alone cost a whole fortune. Amazing jewels, treasures of the West and the East, completed her attire. With pearl beads, heavy golden bracelets with Byzantine patterns, earrings with turquoise and pearls and with rings that glowed with all colors of the rainbow, the princess looked like an ancient empress…”

The Georgian aristocrat was a lady-in-waiting of last empress Alexandra Feodorovna. According to legend, even Emperor Nicholas II was struck by her beauty – having met her, he said: “It’s a sin, princess, to be so beautiful.” After the February Revolution, Mary returned to Georgia and, soon after the Bolsheviks took power there, she fled her homeland and moved to France. There, in 1925, she became a model for the Chanel House.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox