"Two of my acquaintances, guys from Kazan River Technical School, teenagers, 18 years old, are talking among themselves: 'We are eighteen years old, and we haven't killed anyone yet..’ This phrase still sounds like razors in my ears," recalls Radif Zamaliev, a Master of Sport in hand-to-hand combat and a Kazan resident who in his youth witnessed the heyday of the "Kazan phenomenon.” This was the era of rampant and very dangerous youth street gangs that controlled the city's neighborhoods, streets and yards.

"From the age of eleven or twelve, everyone already knew about the criminal groups, about their turf," says Robert Garayev, author of the book Slovo Patsana (The Word of a Thug). The book is a documentary narrative of life in the 1970s-1980s in Kazan, where more than 100 organized youth criminal groups operated.

"Unless you were a member of a group, it was entirely dangerous to walk down the street, because someone was always trying to stop you, take your money, and beat you up," Garayev says. He himself was a member of one such gang.

The gangs truly gripped the entire city with fear and terror. "Many children can't even go out on the street," complained a teacher in the 1988 Soviet documentary "The Vocational School From the Back Door”, which was dedicated to the “Kazan phenomenon” and all its atrocities.

A typical 'drill' (still from 'Slovo patsana' TV series)

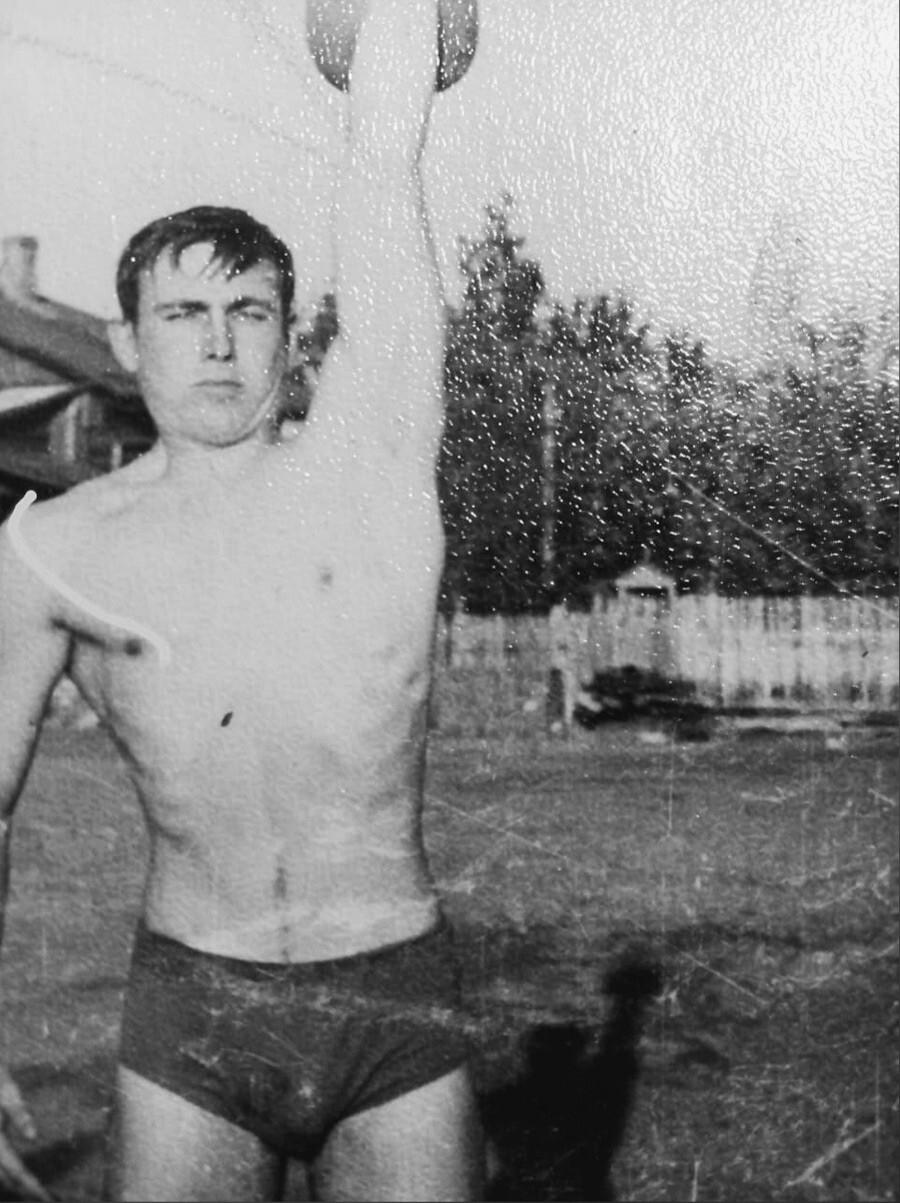

Zhora Kryzhovnikov/Toomuch Production, 2023The first and most famous gang was "Tyap-Lyap", named after the neighborhood of the "Teplokontrol" plant, where most of the gang members lived. One of the group's members, Sergei Antipov, found a room for a "gymnasium" where the barbells were steam-heating radiators and the bar was a gas pipe. In the absence of clubs and official sports programs, this "gym" was almost the only place where teenagers could go in the evening. Those who hung around the gym began to be organized in a certain, and often criminal way.

The members of the group were divided into "ages". The first, called "the shells" (скорлупа), were children in junior high school to 13 years old. The younger ones would stand "on the lookout" when the older ones robbed stores or stalls, but their main function was to gather for the “drills”, and gather and hand in money.

'Teplokontrol' plant in Kazan. This plant gave the name to 'Tyap-Lyap,' one of the scariest youth gangs in Kazan

Archive photoThe second age – "supers", were 14-17 years old, and they had to be constantly on duty in the yards of their neighborhood or turf. They were also engaged in educating the "shells", making sure that they handed in their dues.

The "young ones", those 17-19 years old, were the main fighting force in skirmishes, flying at their opponents with bricks, metal bars, wooden and rubber truncheons. These "young ones" mainly organized raids that were called "good morning" and "good evening". The purpose of such raids was to take the rival gang by surprise, to frighten them, to beat them badly or even to "break them" (inflict severe bodily harm).

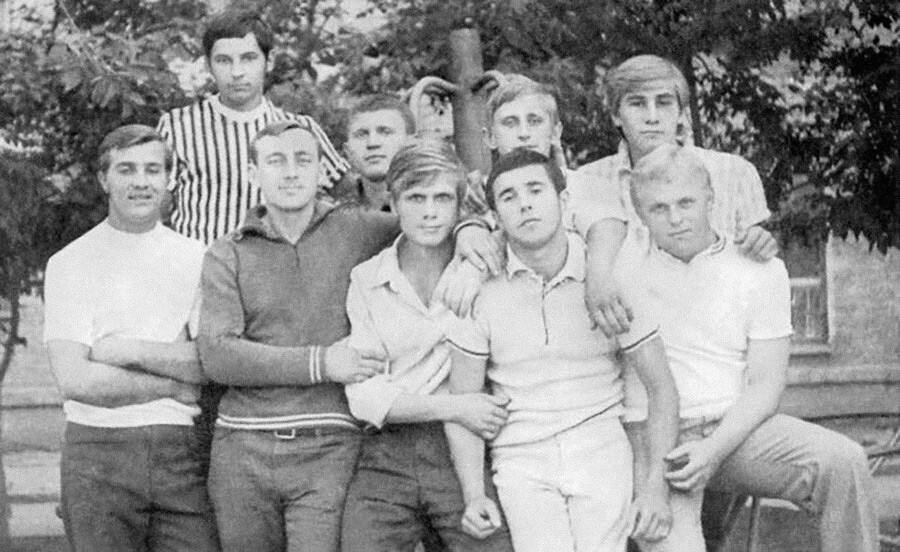

The bosses of the 'Tyap-Lyap' gang, a group photo

Ministry of Internal Affairs in the Republic of Tatarstan"The middles," who were 20 years of age or older, were allowed to visit neighboring areas as peacekeepers. Next were "the old ones", or "army men" who often really had already served in the army. They had the right to start gang wars, go to discos, and control local commercial activities.

Finally, at the head of each gang stood the "authorities”, "grandfathers", and "kings". These were the crime bosses, the equivalents of “dons” and “godfathers”, who determined the Kazan groups’ policies and priorities. There was often an aura of mystique about these powerful crime bosses, and the first two age categories usually didn’t even know them by sight or by name.

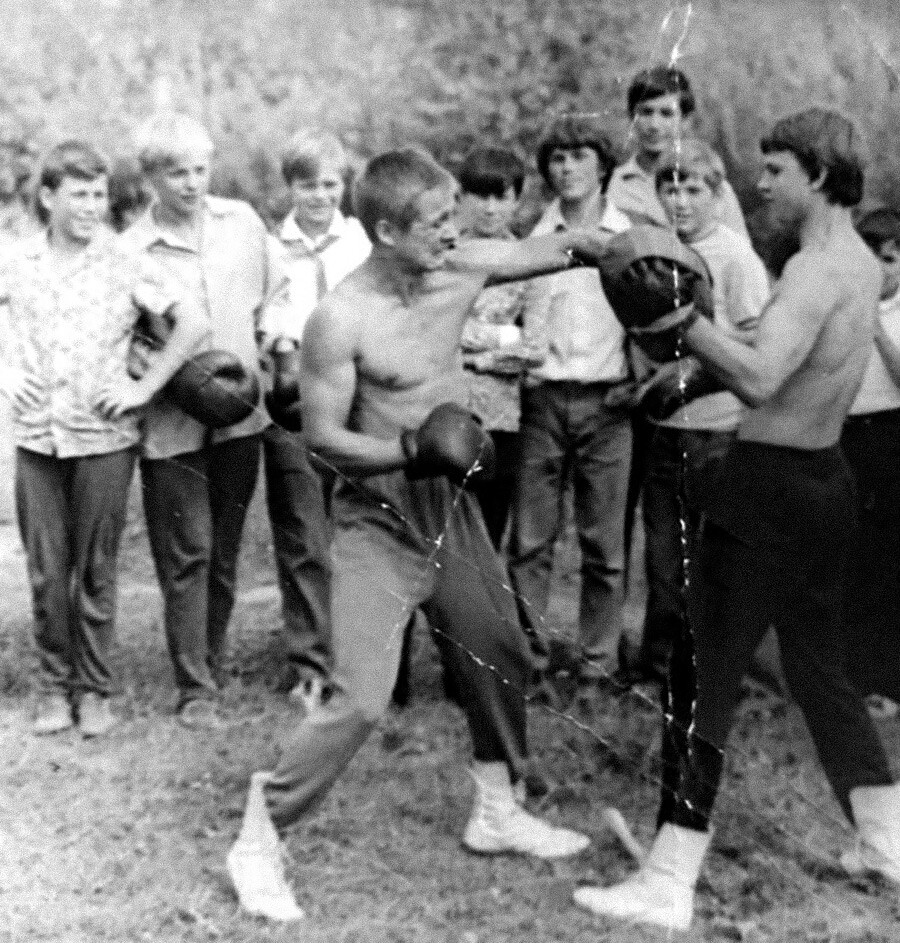

Sergey Skryabin (1956-1994), one of the founders of "Tyap-Lyap" gang, sparring with a partner

Archive photoThe members of the groups did not call themselves "gangs", of course. More accepted names were "motalka" that came from the word "motat’sya" (мотаться) – to participate in the street life of the gang; and another term was "kontora" (‘office’ in Russian). Most often, however, the group was called directly by its name. In Kazan in the 1970s-1980s, dozens, if not hundreds, of different "motalkas" were operating: "Zhilka", "Sukonka", "Hadi Taqtaş", "Tyap-lyap", "Kettles", "Sosnovka", "Pentagon" – all of which got their name from local streets, meeting places, and conventional signs ("Kettles", for example, marked their territory by hanging tea kettles on trees and fences).

READ MORE: Hadi Taqtaş, the killer gang that ruled Kazan

To join a group, one had to pass a sort of initiation that was referred to as "registration" in the local slang. Usually a newcomer was hit hard in the face. If he could resist and/or defend himself, he was accepted into the "kontora". If an older boy wanted to join, he could be forced to attack a random passerby or a member of another "kontora". All members of the "motalkas" were strictly forbidden to smoke, drink, or use any substances. If someone was caught with cigarettes or drunk, then his whole age group faced a severe punishment, often subjected to a humiliating beating. In this way, a powerful sense group solidarity and cohesion was forged in the "kontoras", which united the young hooligans and made them watch out for each other.

Each member had to attend compulsory ‘drills.’ Usually, the boys were called to the drills by their own neighbors, since often the gang members lived close to each other, in the same courtyards and apartment blocks. Drills for younger ages were held almost every day, and this was the reason why teenagers skipped classes. In fact, this was in the interest of the leaders who benefited from the fact that the "shells," the “supers” and the "young ones" were uneducated, often nervous and jittery, and that they saw only one road in life – the one provided by the mean streets.

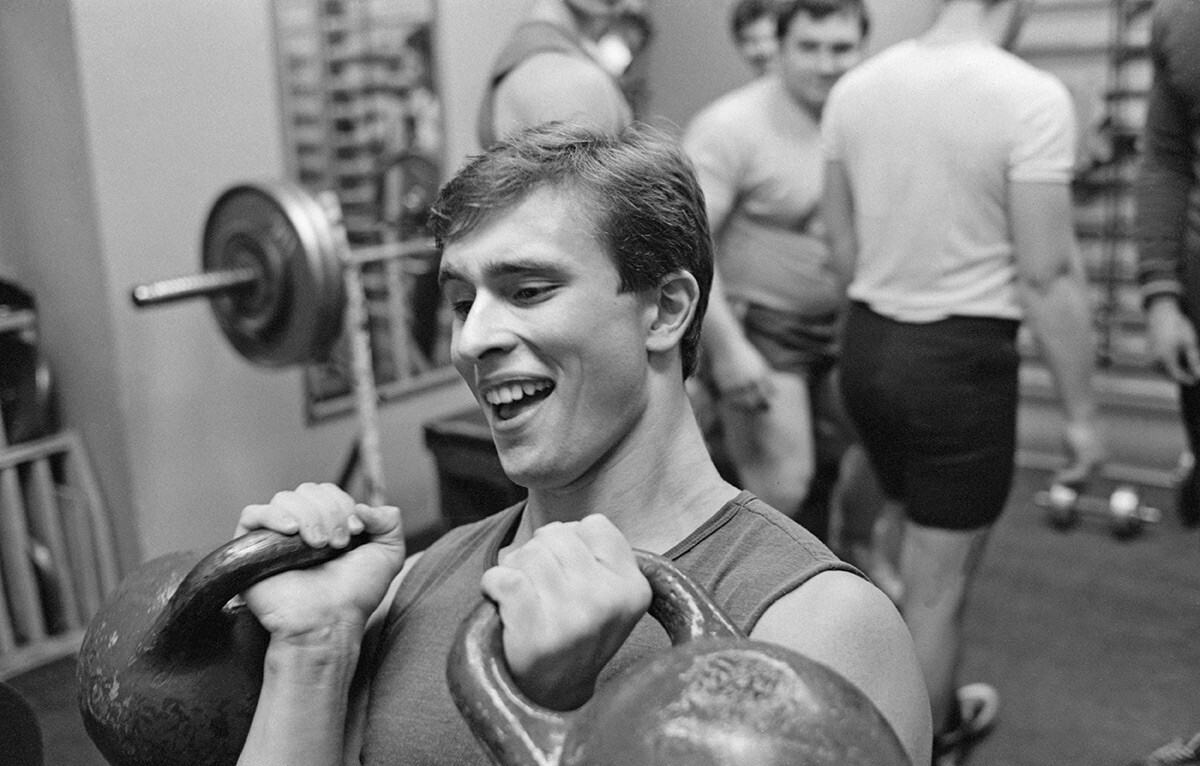

A young man training in a Soviet gym, 1980s

Igor Zotin/TASSDuring the drills, the boys were taught the rules of street morality: you had to keep your word, always protect your yard and your "kontora". If members of another group stopped on the street and asked "Who are you?", the kid was obliged to say which "kontora" he belonged to, even if he realized that he would be beaten. To lie, to hide the fact of participation in a “motalka” was shameful – you would be kicked out from the gang, and beaten very badly, at the very least. Moreover, they would tell everyone about the betrayal, and you would not be able to join any other "motalka", which meant that it would be dangerous to walk down the street.

The guys from “motalkas” were distinguished by their clothes – tracksuits in summer, telogreikas or vatniks (a certain type of Soviet winter coat) and colorful hats in winter. The clothes had to be comfortable for a fight, and the hat had to be thick enough to protect them at least a little when hit on the head with an iron bar or a construction crowbar that the gangs used as most common fighting weapons.

Sergei Antipov from 'Tyap-Lyap' gang lifting a dumbbell

Archive photoThe main function of all the age groups was to contribute money to the general treasury, the "obschak". Where did the youths get the money from? Of course, not from their parents. They robbed and mugged other boys on the street, especially those who didn’t belong to any “motalkas”. These victims were called “chuspany” (from the word chush’, чушь, meaning “nonsense”). Any member of a motalka could stop any chushpan on the street and rob him, take off his overcoat or boots, whatever. Such a way of robbing wasn’t considered unlawful in the codex of the street, because the boys who they were robbing didn’t belong to the criminal world, and were considered useless and unmanly.

The younger ones were told that this money was collected for the material support for "their own" boys, other members of the gang who had been imprisoned. However, often this money was simply appropriated by the higher echelon of the "kontoras", who bought themselves expensive clothes and motorcycles, considered the elite transportation of the "groupers".

Kazan young gangsters as seen in the 'Slovo patsana' TV series

Zhora Kryzhovnikov/Toomuch Production, 2023"They wanted to resemble the Italian mafia – they had seen enough foreign films in cinemas. Who else were they to take an example from?" explains Alexander Raskin, a journalist and researcher of the Russian criminal world. Radif Zamaliev tells about one his gang member acquaintances: "He had a grudge against the street, because when he had been a “kontora” member, he handed over 3-5 rubles weekly, and when he was locked up, they didn't send him a single parcel from the street."

In addition to collecting money from the younger ones, gang members were involved in racketeering of small and medium-sized businesses in Kazan, as well as raids on street sellers.

On August 31, 1978, members of the "Tyap-Lyap" gang staged a massive “run-by” (пробег) in the "Novo-Tatarskaya Sloboda" neighborhood, which was controlled by the eponymous “kontora”. More than 50 teenagers with iron bars and even pistols ran through the neighborhood, attacking everyone indiscriminately. Several dozen people were injured, including women and the elderly, and two people were killed. However, no one filed a police report after the attack – Kazan residents were afraid of retaliation from the gangsters.

Nevertheless, the daring raid led to the arrest of the ringleaders. According to Alexander Raskin, more than 80 people were arrested, while 30 ringleaders went to trial. The ringleader Zavdat Khantimirov was eventually sentenced to death. However, the destruction of “Tyap-Lyap” only stimulated an even greater flourishing of street crime in Kazan.

Soviet special police unit arresting a car thief,1989

Anatoly Semekhin/TASSRobert Garayev attributes the reasons for the emergence of street crime in Soviet cities to government amnesty for prisoners. Criminals who had already fully adopted the underworld way of life returned to society and brought those nefarious values with them. The largest amnesty after World War 2 took place in 1953 just after Stalin’s death, and amnesties were also announced in honor of the 40th (1957) and 60th (1977) anniversaries of the October Revolution.

Also, another factor was the growing urbanization that led to the relocation to Kazan of the population of many villages and hamlets, which retained long-standing habits of fist fights "street to street", "village to village". In addition, some groups grew up in areas that were famous for their "fist fighters" even before the revolution. For example, the population of the Sukonnaya and Staro-Tatarskaya neighborhoods, even under the tsar, would come together in winter to fight on Lake Kaban in Kazan, and these were the most brutal fist fights in Russia.

The structure of the groups resembled that of fist fights, with age division and the leadership role of the ringleaders. As in fist fights, encounters between gangs were fought according to certain rules until first blood was drawn. Likewise, as in fist fights, the violent encounters between gangs often saw people beaten to death.

The police were not at all prepared to confront organized gangs. Alexander Avvakumov, former deputy chief of criminal investigation of the Republic of Tatarstan (Kazan is the capital of Tatarstan), in an interview with journalist Sasha Sulim posed the question: "Do you think that if a battalion of policemen were sent in, that this would change anything? Well, they would have conducted a raid, detained ten people, but it would have been impossible to charge them with anything. The leaders themselves did nothing, others did it for them.” Besides, Garayev recalls, there was no legal basis for arresting gangsters. The very concept of organized crime did not exist in the USSR Criminal Code; in fact, this concept only appeared in the new Criminal Code of the Russian Federation that was adopted in 1997. By that time, there were hundreds of organized crime groups operating in Russia, heirs of the Kazan street gangs.

A photo of the closed trial of members of the 'Tyap-Lyap' gang

Ministry of Internal Affairs in the Republic of Tatarstan"Every era has large criminal groups, and the members of gangs such as"Tyap-Lyap," with their rules for codifying and giving structure to criminal activity, went on to inspire and serve as models for future organized criminal groups in the 1990s," explains Alexander Raskin.

In the end, the “Kazan phenomenon” was never liquidated or eradicated. The gang members simply grew up and joined the "adult" crime of the 1990s, when money was taken not from schoolchildren on the street, but from corporations, factories, and city administrations.

The collapse of the USSR changed society’s values and gave young people more opportunities to learn and develop. The basement gyms were no longer the only place to go in the evening. While street crime in the cities remained a serious problem for many more years, belonging to a gang was no longer necessary for teenagers in the 1990s.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox