In July 1921, Lenin wrote to Maxim Gorky: "I am so tired that I can do nothing". Nevertheless, he sometimes attended up to 40 meetings and committees a day, and received dozens of people. "From the meetings of the Sovnarkom," recalls his sister Maria Ulyanova, "Vladimir Ilyich returned home in the evening, or rather at night at 2 o'clock, completely exhausted and pale; sometimes he could not even speak, neither eat, and poured himself only a cup of hot milk and drank it, walking around the kitchen, where we usually had dinner.”

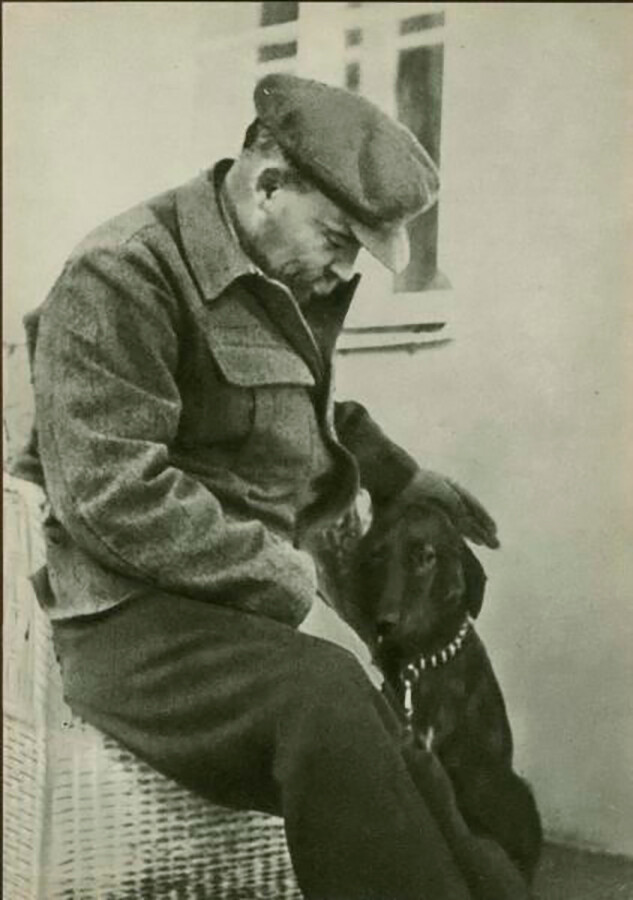

Vladimir Lenin with a dog named Aida in Gorki, 1922

MAMM/MDF/Russia in photoProfessor Liverij Darkshevich, who examined Lenin in March 1922, noted "a mass of extremely severe neurasthenic manifestations, completely depriving him of the ability to work as he had worked before" and "a number of obsessions, which greatly frightened the patient." "Surely this does not threaten insanity?" Lenin asked the professor.

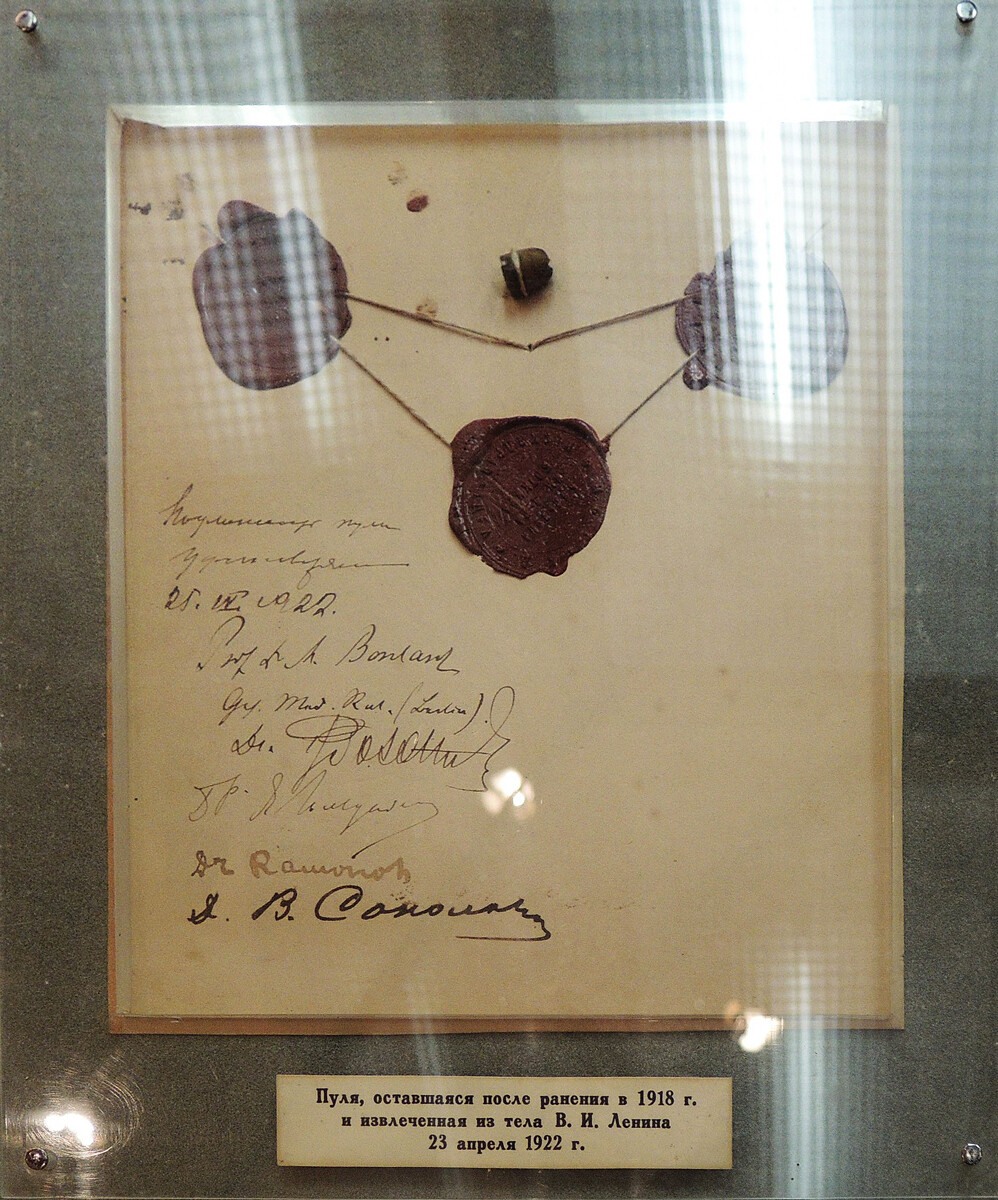

A bullet from Brauning pistol that was taken out of Lenin's body on April 23rd, 1922

Wikipedia / ShakkoIn April 1922, Lenin became so sick that doctors suggested he might be facing some sort of poisoning from the lead bullets that were stuck in his body after Fanny Kaplan’s assassination attempt on August 30, 1918. As the surgeon, academician Yuri Lopukhin writes, "the decision is very controversial and doubtful, given the four years that have passed since the assassination attempt. By that time, the bullets were already surrounded with protective tissue, and, as professor Vladimir Rozanov (one of Lenin’s physicians) believed, the operation to extract them will bring more harm than good".

On April 23, 1922 German surgeon Borchardt removed a bullet from Lenin's body, and on April 27 Lenin was already at a Politburo meeting. He continued to work actively for another month, until on May 25 while at the Gorki estate (seven kilometers from Moscow) he suffered his first stroke. After that, Lenin began to lose his ability to speak, he periodically could not read and write, and he had little control over his right hand.

On May 29, there was a meeting of the large group of doctors who tended to Lenin – among them was the great neurologist Grigory Rossolimo and the People's Commissar of Health Nikolai Semashko. They recognized that the nature of the disease was unknown, but they assumed that it might be sclerosis of the arteries of the brain. However, the doctors were struck by the fact that Lenin's intellect remained fully functional, and that there were temporary improvements in his condition.

Lenin in Gorki in 1923

Public DomainOn May 30, immediately after the meeting of the group of doctors, Lenin asked Joseph Stalin to come to Gorki. As Yuri Lopukhin wrote, "knowing Stalin's firm character, Lenin asked him to bring poison (cyanide) to end his life". However, Stalin managed to persuade Vladimir Ilyich to undergo treatment. In the summer of 1922, Lenin's condition began to improve. On June 16, he was allowed to get out of bed, and, as nurse Petrasheva said, the leader "went into a dance with me.” Nevertheless, pathological manifestations continued throughout the summer, and Lenin sometimes lost his balance. On August 4 he had a spasm with loss of speech after an injection of arsenic that was used to treat him.

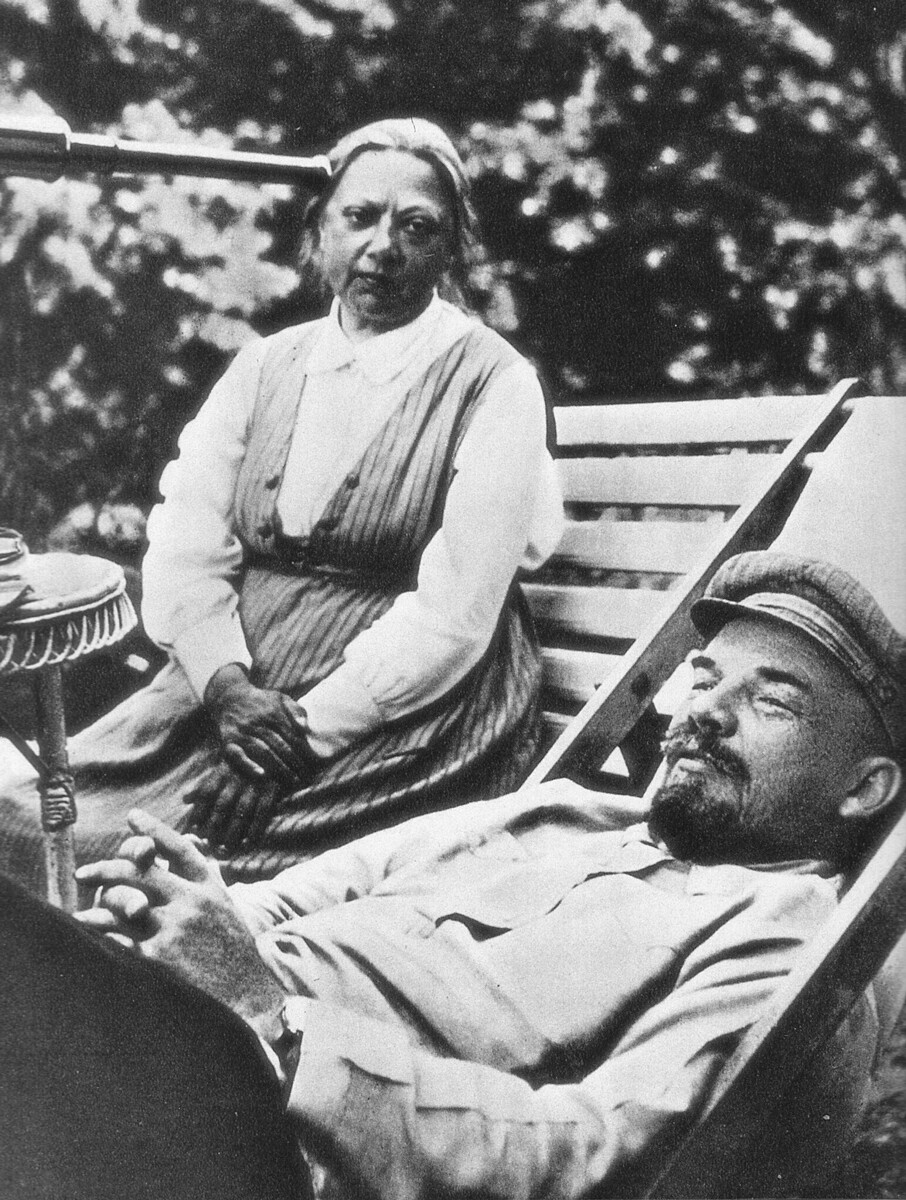

Nadezhda Krupskaya and Vladimir Lenin in 1922

Public DomainLess than five months after the stroke, Lenin returned to Moscow on October 2, 1922. His professors believed that he had fully recovered, but he himself admitted: "Physically I feel well, but I no longer have the same freshness of thought. I have lost my ability to work for quite a long time."

In October and November, Lenin participated in many meetings of the Council of People's Commissars, and also spoke at congresses and rallies. His strength left him by December 7, when he left Moscow for Gorki. On December 12, Lenin returned to Moscow, where he suffered several seizures and a stroke (December 16); after which, the right side of his body became paralyzed.

On December 24, 1922, Stalin convened a meeting with Soviet leaders Lev Kamenev, Nikolai Bukharin and Lenin's doctors. It was decided to keep Lenin away from news about political life, "so as not to provoke reflection and excitement". Lenin was also banned from seeing visitors. Despite this, Lenin continued to dictate notes and letters until March 9, 1923, when he suffered his third stroke. Lenin was again rendered speechless, and after that he never returned to work again.

In the summer of 1923, he was forced under the supervision of Nadezhda Krupskaya to re-learn to walk, take objects, and speak separate words. Krupskaya wrote: "Walks now (with help) a lot and independently, leaning on the railing, goes up and down the stairs. [...] His mood is very good, and now he sees that he is recovering". On October 18-19, Lenin was in Moscow for the last time, after which he stayed only at the dacha in Gorki.

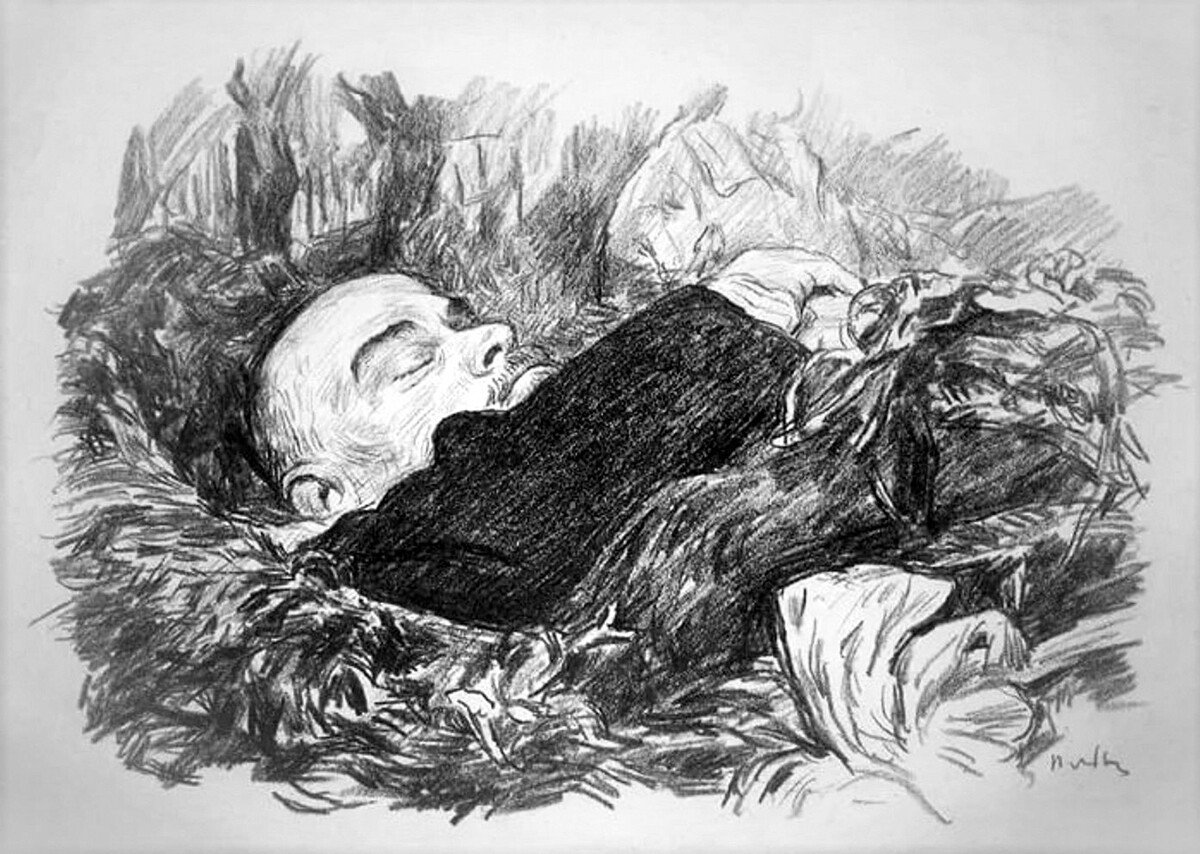

Lenin on his deathbed by Peter Lvov, 1924

Public DomainVladimir Lenin died in Gorki near Moscow in the evening of January 21, 1924, at 6:50 PM. He was 53 years old. The autopsy was performed the very next day at 11 o'clock. This is the most important mystery of Lenin's death – why wasn’t the body of the founder of the Soviet state taken to Moscow, which had the best medical institutes and facilities to perform an autopsy? And why did they begin the autopsy in the bathtub at the dacha in Gorki?

Lenin after his death in Gorki, January 1924

TASSThere are two versions for the main cause of Lenin's death – atherosclerosis of cerebral vessels and syphilis. Still, a hundred years after his death, there is no consensus on this issue. Academician Yuri Lopukhin suggests that the true cause of Lenin's illness and death was poor blood supply to the brain, which occurred after Lenin was wounded in 1918.

Many of the archival documents about Lenin's death and illness remain classified at the request of his niece Olga Dmitrievna Ulyanova (1922-2011), but their secret status expires in 2024.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox