How the Bolsheviks’ most devoted supporters rebelled against them

"May the hated yoke of the communists be cursed! Long live the freely elected Soviets (councils)!" Such slogans were heard at the Soviet Baltic Fleet base in the city of Kronstadt in March 1921.

There, on the island of Kotlin, only 30 kilometers from Petrograd (now St. Petersburg), sailors, who were considered as Bolsheviks’ most reliable fighters, Lenin's Praetorian Guard, "the beauty and pride of the Russian Revolution", began to rebel against the country’s leadership.

Outrage

Pockets of public discontent were then emerging all over Russia. The economic situation in the country devastated by the Civil War was catastrophic: industrial production collapsed, while agriculture was also in a deep crisis, which immediately led to famine.

Confiscation of agricultural products from peasants.

Confiscation of agricultural products from peasants.

The war was largely over, but Soviet authorities still pursued a strict policy of "war communism" with the prohibition of private property and ‘prodrazverstka’ – the forcible seizure of food from the peasantry for the needs of the state.

The sailors, many of whom came from peasant backgrounds themselves, were well aware of the dire situation.

"We knew that our families were crushed by the ‘prodrazverstka’, terrorized by the ‘prodotryadami’ (military units who conducted ‘prodrazverstka’), driven to starvation and we could see no light ahead, no hope for improvement," sailor Ivan Yermolayev recalled. “Often in conversations about the situation in the country murmurs broke out and, at meetings, there were proposals to appeal to the government with demands to ease the plight of the peasantry, to abolish the ‘prodrazverstka’, to remove the ‘prodotryadas’ and to allow free trade."

On February 23, a strike began in Petrograd by workers at the Pipe Factory, which was quickly joined by their colleagues throughout the city. At the Baltic Fleet base in Kronstadt, the situation was closely monitored.

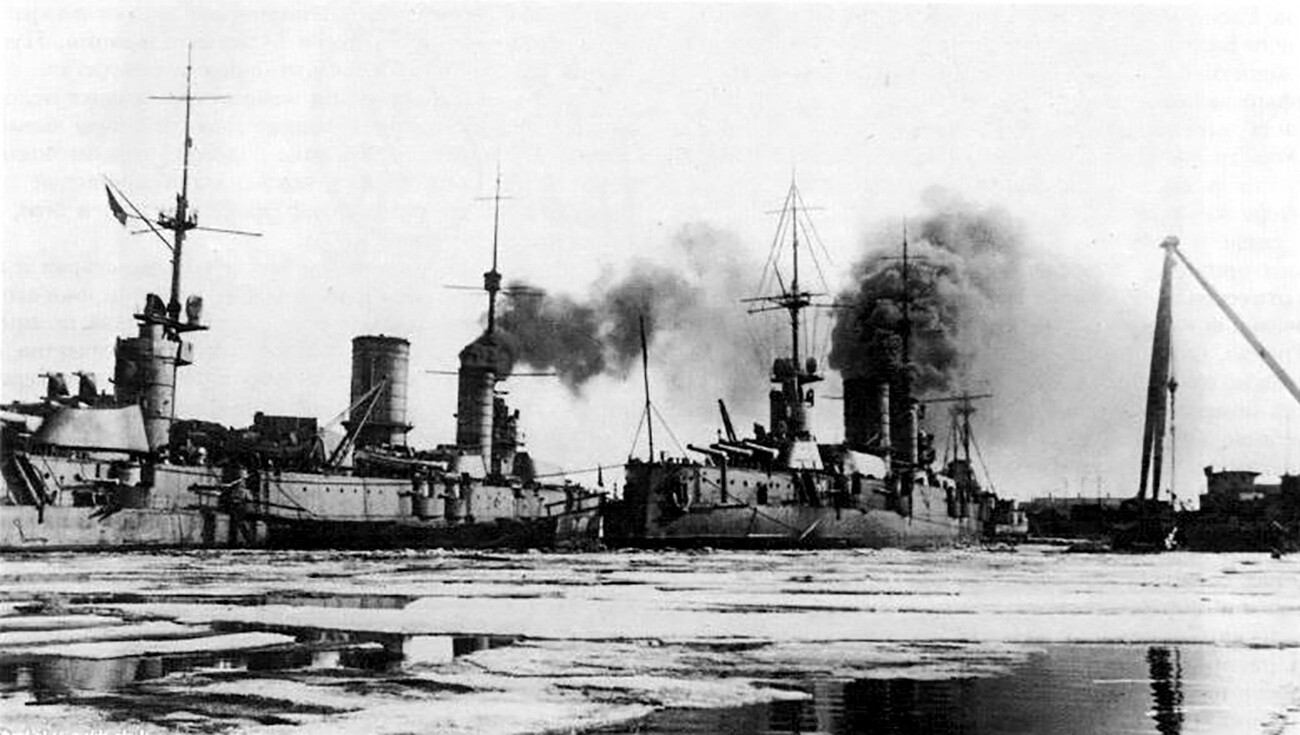

Battleships ‘Petropavlovsk’ and ‘Sevastopol’ in 1921.

Battleships ‘Petropavlovsk’ and ‘Sevastopol’ in 1921.

Authorities partially met the protesters' demands by increasing their food rations. At the same time, they arrested the main activists and threatened the rest that they would use force if the riots continued.

By the end of February, the situation in Petrograd began to normalize, but, in Kronstadt, everything was just beginning.

Mutiny

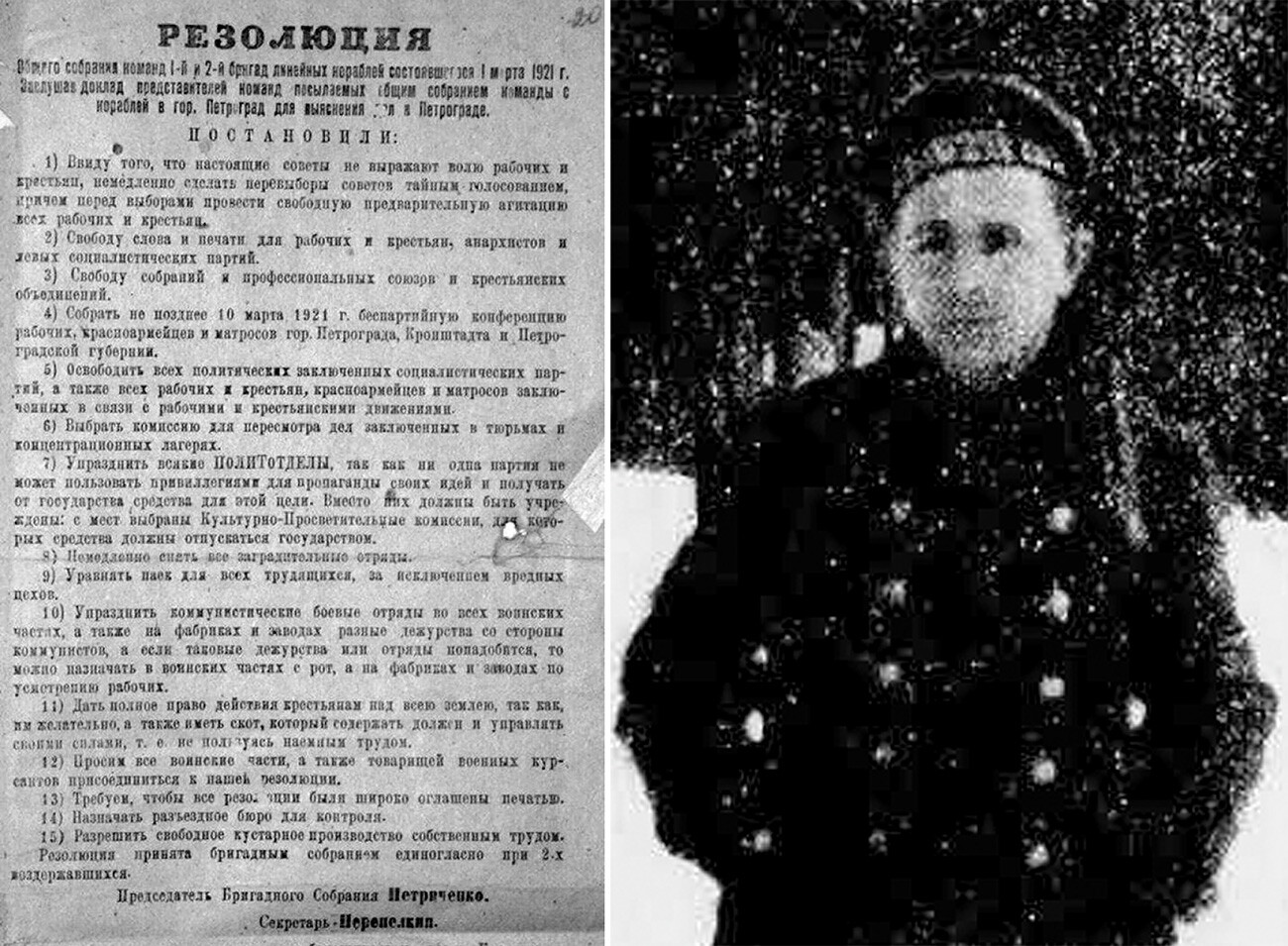

On February 28, the crews of the battleships ‘Sevastopol’ and ‘Petropavlovsk’ adopted a resolution, in which they actually demanded from the Bolsheviks to ease the life of the peasantry, giving them the right to unlimited disposal of their land and livestock.

At the same time, the document contained political demands: to hold re-elections to the Soviets (councils), to grant freedom of speech and press to anarchists and left-wing socialist parties, to release all left-wing political prisoners, to limit communist propaganda and to reduce the number of communists in the army.

Rsolution/Stepan Petrichenko.

Rsolution/Stepan Petrichenko.

The resolution was publicly announced on March 1 on Kronstadt's Anchor Square, where a 15,000-strong rally was held under the slogan: "Power to the Soviets, not to the parties!" The next day, the protesters (sailors, soldiers of the fortress and some local residents) proclaimed the establishment of the Provisional Revolutionary Committee headed by Stepan Petrichenko, the clerk of the ‘Petropavlovsk’.

Local newspaper ‘Izvestiya’ openly wrote about the beginning of the third Russian revolution (after the February bourgeois and October Bolshevik revolutions), about the merciless war against the "commissarocracy" until the victorious end. "Instead of the free development of the individual, free labor life, an extraordinary, unprecedented slavery has arisen," its pages said about the current political situation.

The Kremlin perceived the sailors' speech as an attempted coup d'état and refused all forms of dialog. Kronstadt was blockaded by Red Army units, cutting off the mutineers from sympathizers in Petrograd.

The first assault

The Bolsheviks tried to solve the Kronstadt problem as quickly as possible, while it could still be reached by ice. In addition, the mutiny began to attract more and more attention abroad.

The Red Army attacks Kronstadt in March 1921.

The Red Army attacks Kronstadt in March 1921.

On March 4, the sailors were told to "immediately and unconditionally surrender". After their refusal, the city was bombed from the air, while troops began to prepare for an assault.

Commander of the 7th Army Mikhail Tukhachevsky had more than 17,000 soldiers at his disposal. They were opposed by 13,000 sailors and soldiers of the fortress, as well as two thousand armed citizens.

The assault on March 7 ended in complete failure. There was haste in its organization, lack of forces and low morale of the personnel. Many Red Army soldiers refused to fight against the "brothers of Kronstadt" and some even went over to their side.

The second assault

The next attempt was prepared much more thoroughly. The grouping of troops grew to 45,000 men, among whom were many reliable and convinced communists. The forces of the defenders grew to 18,000 at the expense of defectors and volunteers from the townspeople.

Soviet artillery shells the Kronstadt forts.

Soviet artillery shells the Kronstadt forts.

The second assault began with a massive artillery preparation on March 17. After it, detachments of Red Army soldiers rushed to the attack on the ice of the Gulf of Finland in the direction of the forts.

"It was a multi-story row of concrete block houses with built-in machine gun nests, entangled in all directions with electric cable and barbed wire,” recalled Elizabeth Drabkina, a participant in the assault. “The closer to Kronstadt, the more dead and wounded there were on the ice. Two hundred meters away from the wall, the dead, mowed down by machine guns, were lying in three even rows, at regular intervals."

The Red Army took one fort after another. Soviet aircraft hit the ‘Petropavlovsk’ and the ‘Sevastopol’, while Tukhachevsky ordered to attack the battleships with "asphyxiating gasses and poisonous shells", as well.

Eventually, the fighting began in the streets of Kronstadt itself. The fierce resistance of the defenders allowed 8,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and local residents, along with the head of the Provisional Revolutionary Committee, Stepan Petrichenko, to escape to Finland.

Suppression of the Kronstadt mutiny.

Suppression of the Kronstadt mutiny.

By noon on March 18, the city was completely taken by the Red Army. As a result of the assault, a little less than 2,000 of its soldiers were killed, while Kronstadt residents lost about 1,000.

Repressions

The Bolsheviks could not leave such treachery unpunished. As Lenin remarked in a conversation with French socialist Jacques Sadoul, speaking of the mutiny, "This is ‘Thermidor’. But, we will not let ourselves be guillotined. We will commit ‘Thermidor’ ourselves!"

More than 2,000 rebels were shot, while 6,500 were sentenced to imprisonment. By President Boris Yeltsin's decree of January 10, 1994, all participants of the Kronstadt Uprising were posthumously rehabilitated.

The mutiny of the most reliable fighters and the support they received among other military units shocked and frightened the Soviet leadership. This event, together with a large-scale uprising in Tambov province, forced Lenin to abandon "war communism" as soon as possible.

Vladimir Lenin and soldiers who participated in the suppression of the mutiny in Kronstadt.

Vladimir Lenin and soldiers who participated in the suppression of the mutiny in Kronstadt.

Already on March 21, 1921, the ‘prodrazverstka’ was replaced by a natural ‘prodnalog’ (a tax on food production), which was half as much. In order to revive the economy, authorities decided to temporarily deviate from their principles and implement a limited "restoration of capitalism" in the country with partial denationalization of industry, the introduction of freedom of trade, wage labor, etc.

The so-called ‘New Economic Policy’ was pursued by the USSR leadership until the late 1920s, when it was replaced by collectivization and industrialization.