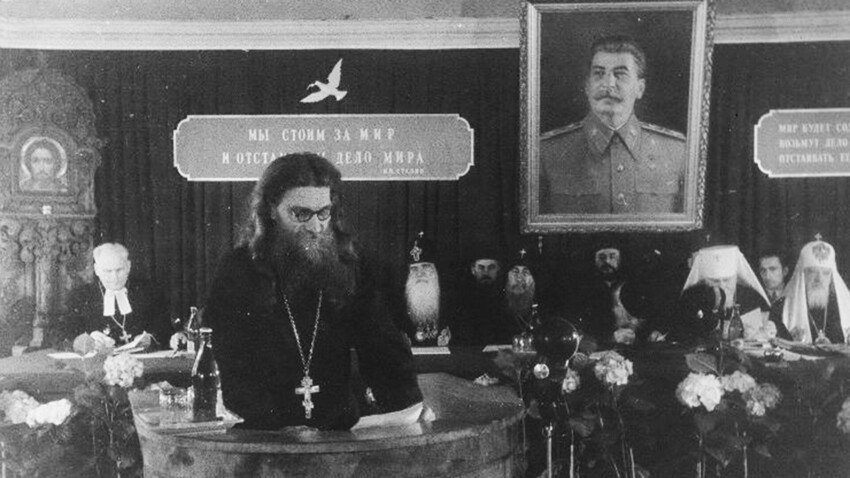

The clergy conducting their meeting under Stalin's' portrait, 1940s.

MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruThe history of the Soviet authorities’ fighting against religion and the Russian Orthodox Church is quite dramatic and complicated. We've already written in detail about it here. We would only remind you that the first priest was killed already in 1917. Then, the Bolsheviks seized the church property and valuables, cynically looted shrines with holy relics and demolished entire churches. This active phase of the antireligious campaign continued until the late 1930s, accompanied by propaganda and numerous posters presenting the priests in an unfavorable light.

Many priests actively resisted, so criminal cases were opened against them and many were persecuted or died in Gulag camps. In the year 2000, more than a thousand priests of the Russian Orthodox Church, who were killed by the Bolsheviks after the 1917 revolution, were canonized.

“There are almost no studies devoted to the facts of cooperation between the Church and the Soviet authorities,” writes historian Nikolai Zayats.

Red Army soldiers take out icons and church items from the Simonov Monastery, 1923

S.Burasovsky/russiainphoto.ru“Because of this, the impression is created that representatives of the clergy sympathetic to the revolution were completely absent and that they all took an anti-Bolshevik or apolitical position, being victims of the government.”

But, it turns out that there were also churchmen loyal to the Bolsheviks, who were later called ‘red priests’. Soviet newspapers wrote about the messages of priests from different regions with words of support for the Party and the power of the workers. Often lower ranks, dissatisfied with the behavior of the higher church hierarchs, “converted” to the Bolshevik faith. This, of course, led to conflicts and even scuffles among the old clergy and the red priests.

There were also cases (though not of a mass character) when priests left the Church.

A Vologda parish priest named Dmitry Popov, for example, became an active participant in the revolution and even personally blessed the Red Army. Archimandrite Irinarkh, an abbot at a Turkestan monastery, left the monastery and joined the Bosheviks ranks.

One of the most famous ‘red priests’ was Mikhail Galkin. During World War I, he was a regimental priest and then served in the St. Petersburg church; he was also an activist and a man with “progressive” views, even advocating the separation of Church and state.

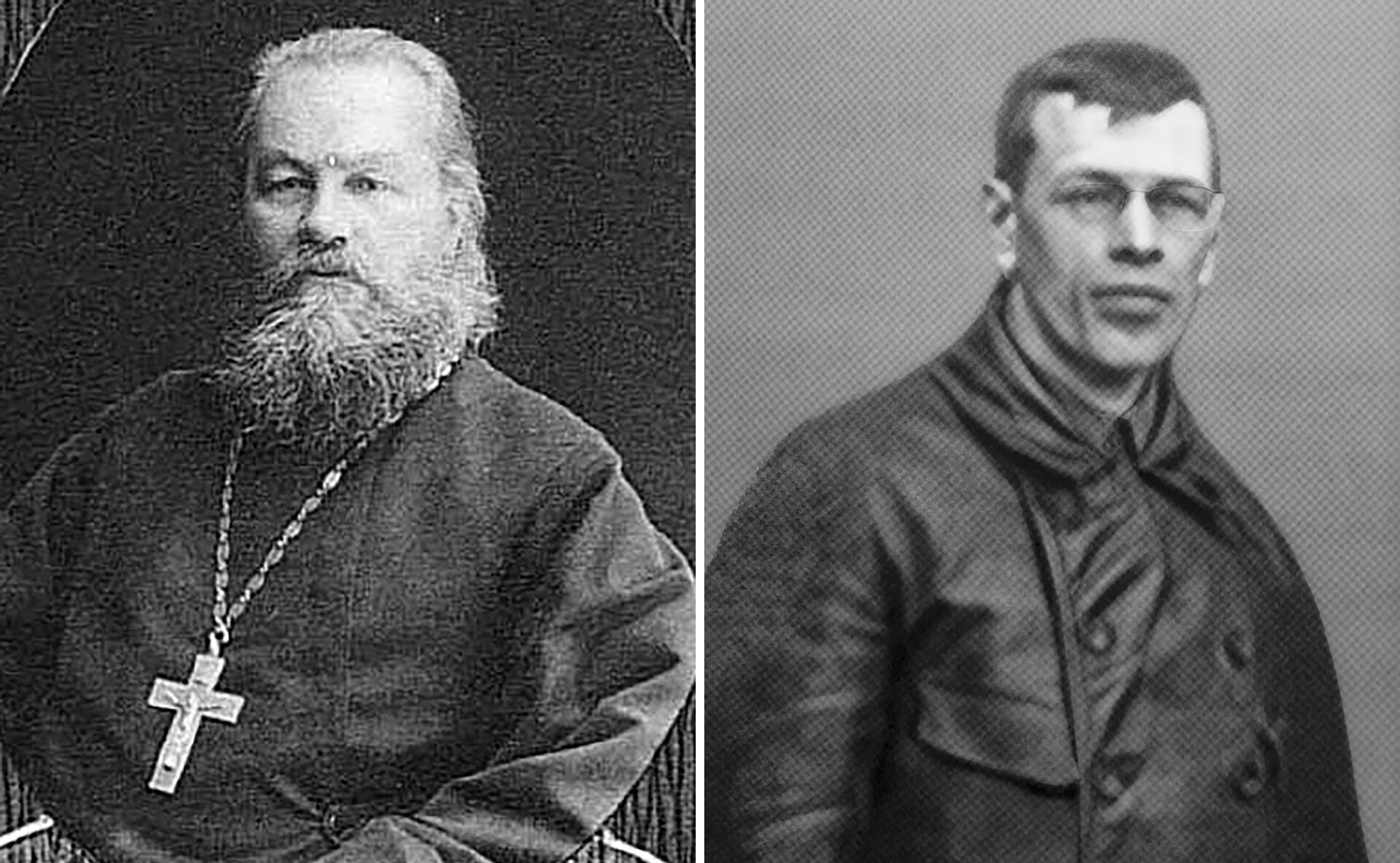

Dmitry Popov (left); Mikhail Galkin

Public domainIn 1918, a Church council condemned Bolshevism in the Church circles and announced that some priests actively supported the revolution, including Galkin personally. As a result, he left the Church, became involved in antireligious propaganda, began working at the ‘Bezbozhnik’ (literally 'The Godless') newspaper and, later, taught Marxism-Leninism.

In 1922, Soviet authorities arrested Patriarch Tikhon, who had denounced the bloodshed and the Civil War. After that, the ‘Renewalist’ schism began in the Church.

Under the active influence and assistance of the NKVD (secret police, future KGB), a group of priests loyal to the Soviet regime dispersed among the clergy. They proposed to “renew” the institution of the Church and to carry out reforms.

Tikhon blesses women's battalion before sending to the front, 1917

MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruMany parishes joined the ranks of the ‘renewalists’, because the churches of priests loyal to the Soviet power were not closed and they were allowed to conduct services there. However, after Patriarch Tikhon was released from arrest, many returned to the “patriarchal” church, even though it was already outlawed.

Later, a split occurred within the ‘Renewalists’ themselves and several other currents emerged, all with different ideas about how the Church should be reformed. And many of these groups had leaders with personal ambitions. But, the Soviet authorities put an end to this turmoil of minds and created a unified church administration, the Synod.

One of the bright leaders and active contributors to the ‘Renewal’ movement was Alexander Vvedensky, who also was involved in Tikhon's arrest. He later became a member and then head of the Synod.

Alexander Vvedensky

So, for a while, there was an official Church, but there were also underground priests, who did not want to go over to the side of Soviet power. During the Great Purge in the late 1930s, however, Soviet leadership repressed both.

During World War II, Stalin suddenly decided to rehabilitate the Church, but it was the old, patriarchal Church. In 1943, he met with church bishops, allowed services, celebrating of Easter and Christmas and promised to reopen some closed churches and monasteries. That same year, a new patriarch named Sergius was elected and the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate was established.

Moscow's Church of St. Pimen the Great in Novye Vorotniki was a cathedral of the ‘Renewalist’ Church and Alexander Vvedensky

Solundir (CC BY-SA)“The main content of the ‘Renewalist’ schism was not at all in liturgical reforms, but in compromise with Soviet power, in the search for a new ‘symphony’ with the state, in adaptation to it. The ‘Renewalists’ followed the path of nationalization of the Church, but the godless state quickly ran out of need for their services and completely abolished this movement during World War II,” says priest Ilya Solovyov, candidate of historical sciences and theology.

The ‘Renewalists’ began to join the Moscow Patriarchate en masse. Feeling on the sidelines, Alexander Vvedensky tried to find a consensus between the Patriarchate and the ‘Renewal’ Churches and even wrote letters to Stalin. But all to no avail. And, after Vvedensky's death in 1946, ‘Renewalism’ essentially disappeared.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox