1. Not only children, but also adults could master the school curriculum. A system of evening schools was created especially for them, so that they could attend classes after their work shift. Before the revolution, only clubs and people's houses with general education classes operated for adults.

In the movie ‘Big School Break’ (1972), the main character Nestor Severov gets a job at an evening school. Most of the students turn out to be older than their class teacher: some of them fall asleep during the lessons after work, while some of them have to be searched for on the dance floors.

2. Contrary to common belief, education in Soviet schools was not always free. Once, Soviet authorities decided on an experiment: from 1940 to 1956, high school students had to pay for their education - about 150-200 rubles per year.

Soviet newspapers of that time explained the need for payment by "parasitic sentiments" and complained that the fee still only covered part of the costs of education.

3. Soviet schools had a six-day week: on Saturday, children also went to lessons.

This was also because there were 30-40 people in classes and it was necessary to make a schedule in several shifts that took everyone into account.

4. From 1943 to 1954, boys and girls studied separately in Soviet schools. These rules applied to schools in Moscow, Leningrad, large industrial cities, republic capitals, regional and provincial centers.

It was believed that separate education had a better effect on the discipline of children. In any case, the number of medal winners increased significantly: In 1953, there were 10.5% of them among girls and 11.6% among boys. In co-educational schools, this figure was 4.4%. There was also another reason: military subjects appeared in the boys' curriculum.

5. For a long time, there was no unified school uniform. In 1918, it was canceled for quite prosaic reasons. Firstly, they did not want it to be associated with the remnants of the past - pre-revolutionary gymnasiums. Secondly, due to the poverty of the population, there simply was no money to buy uniforms.

A unified uniform for schoolchildren in the USSR was introduced only in 1947. It had to be purchased at one's own expense.

In the mid-1980s, a separate uniform for high school students appeared: girls in middle school wore brown dresses and aprons (black for everyday wear and white for special occasions) and, in the ninth and tenth grades, they wore a blue three-piece set consisting of a skirt, vest and jacket. To make the uniform stand out from their classmates' outfits, girls resorted to various tricks. For example, they “refreshed” it with blouses or shirts, alternating a jacket and vest. Or shortened dresses, although school management tried to fight this.

By the way, a student could be sent home for an untidy appearance and the absence of a uniform, even for a good reason - for example, it had not had time to dry after washing - did not justify it in any way.

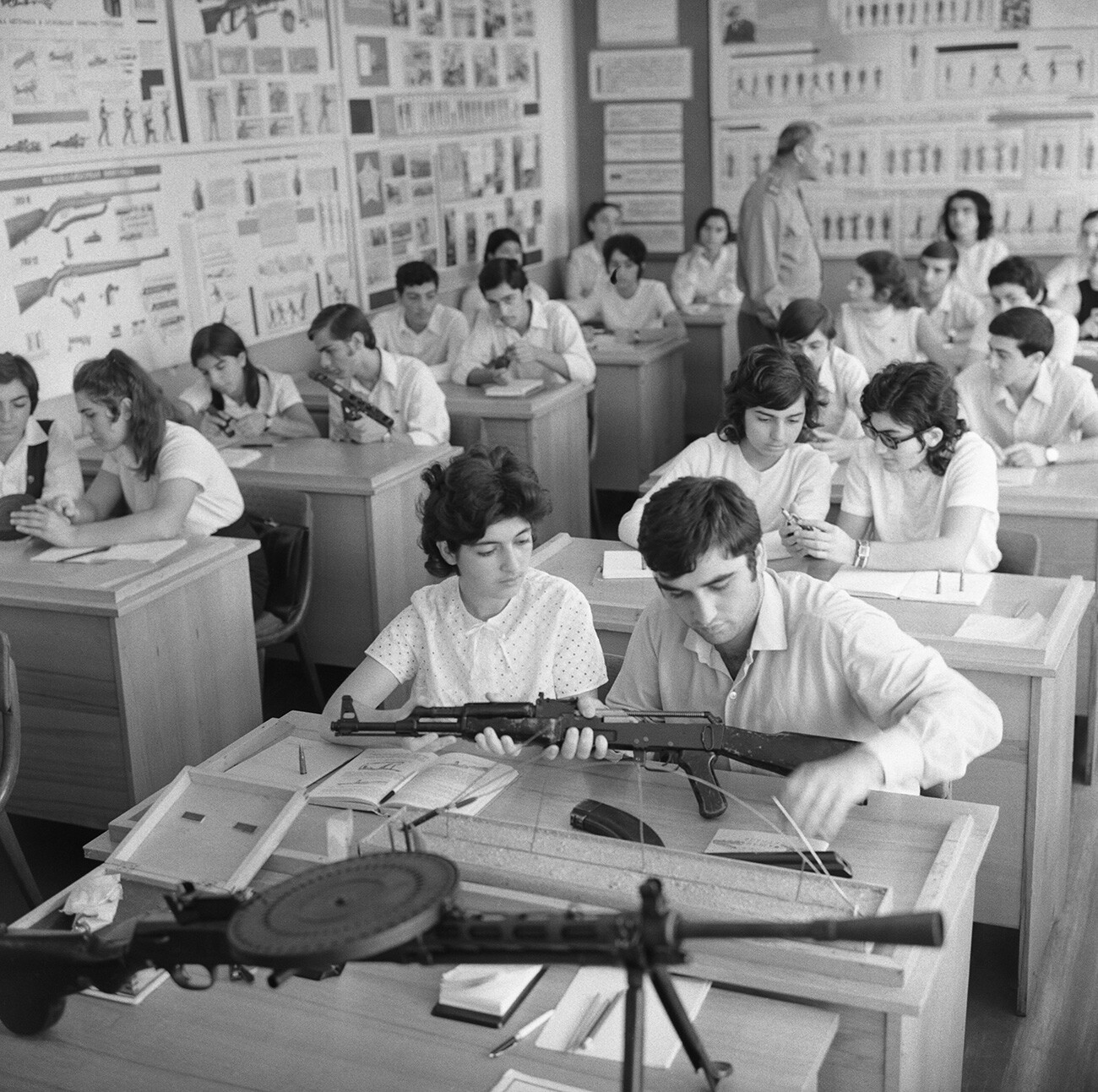

6. In addition to general education subjects, in the mid-1960s, basic military training and the basics of the Soviet state and law were added to the school curriculum.

And, in the summer, middle and high school students had summer work experience - they looked after the lawns on the school grounds, washed the windows in the classrooms and high school students could go to a labor camp to harvest crops on collective and state farms.

7. In the 1920s and 1930s, Soviet schools used a variety of experimental practices. These included the laboratory-team teaching method (the so-called ‘Dalton Plan’). There were no lessons and students worked individually or in teams. Teachers were something like consultants.

"The Dalton Plan is being introduced in our school. This is a system in which the ‘shkrabs’ (school workers - Ed.) do nothing and the student has to find out everything themselves. At least that's how I understood it. There will be no lessons as they are now, but students will be given assignments. These assignments will be given for a month, they can be prepared both at school and at home and, once prepared, present them in the laboratory. Laboratories will replace classrooms," says the hero of Nikolai Ognev's book ‘Kostya Ryabtsev's Diary’.

8. The main accessory of Soviet schoolchildren was a schoolbag for textbooks, notebooks and stationary. Before the revolution, they were used by high school students, but, in the first years of Soviet power, along with the uniform, bags were canceled. They were only returned in the 1950s.

Over time, they became noticeably lighter and "more cheerful" - the lids of school bags were decorated with appliques - cartoon and fairy-tale characters. However, this did not make the uniform bag any less despised.

In the 1980s, however, instead of schoolbags, sports bags and ‘diplomats’ (briefcases) began to be used - high school students often flaunted these plastic and leather cases.

9. No makeup or jewelry - this was strictly prohibited in Soviet schools.

Violators could be sent to wash it off in the toilet - washing off mascara with cold water was a real pleasure.

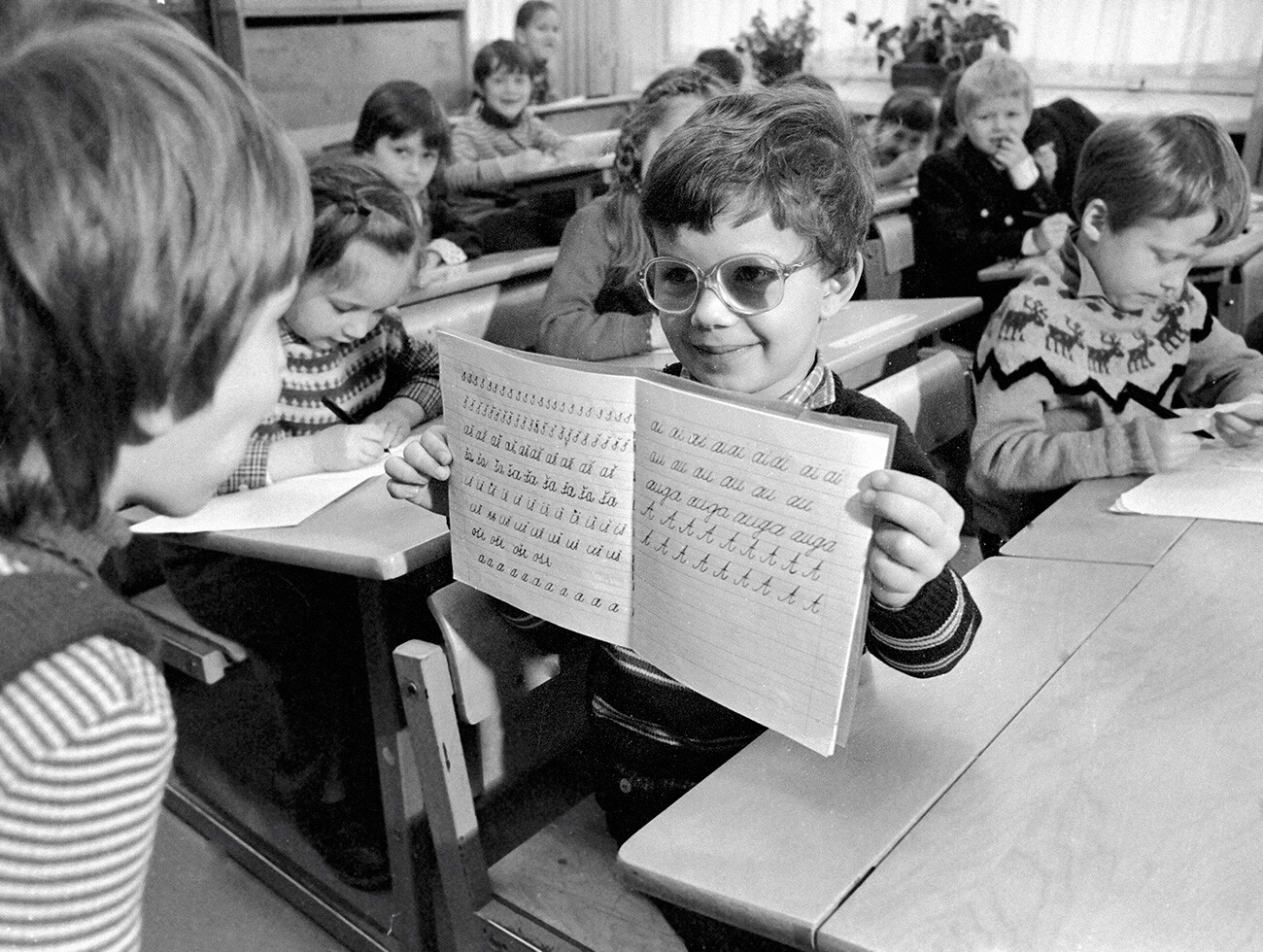

10. “Write different letters with a thin pen in a notebook” - for a very long time, Soviet school children wrote with pens. And they always had a spill-proof inkwell or ‘nepolyvayka’ in their schoolbag. They were replaced by piston fountain pens, which were filled with ink. It was difficult to do homework or fill in a copybook in a hurry: one extra movement - and a blot would spread across the page. After all, teachers scolded for such “dirt” marks in notebooks.

In the 1948 movie ‘First Grader’, one of the girls, having picked up a pen for the first time, immediately makes a blot - and her friends whisper in fear. But, this time, the teacher comes to the rescue, offering to start working on a new sheet.

Ballpoint pens appeared in schools in the mid-1970s, but only schoolchildren were happy about them. Teachers, on the contrary, believed that good handwriting could only be developed using fountain pens.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox