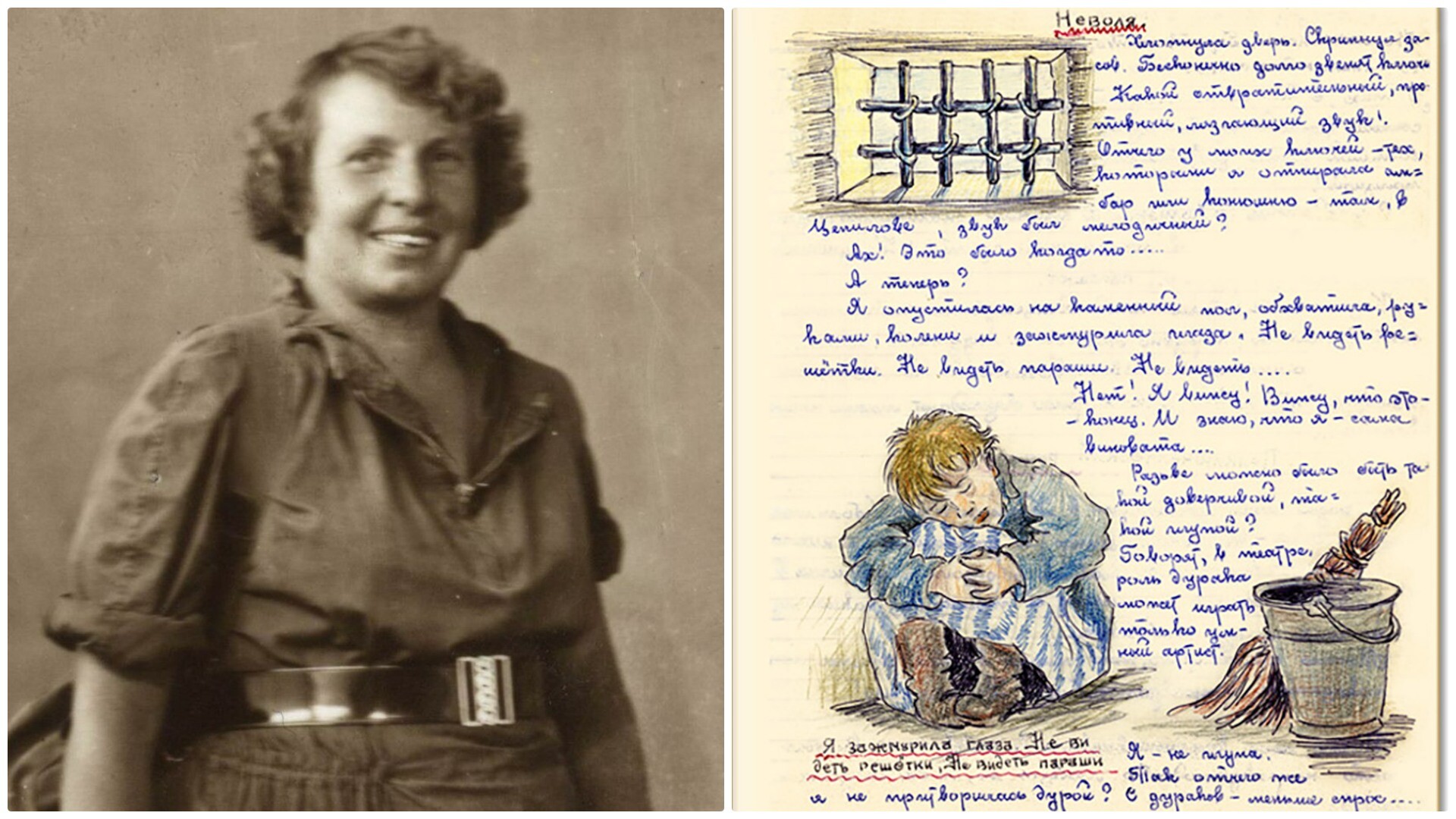

In Euphrosinia Kersnovskaya's naïve, almost childlike drawings, one can see that they are absolutely not childish subjects. The deportation of people to Siberia in cattle cars, night prison abuse, interrogations, corpses, camp towers and the hardest work in the mines.

In her school notebooks, Kersnovskaya meticulously sketched an entire chronicle of her Gulag experience. The 2,200 handwritten pages and 700 drawings became the most vivid testimony of the horrors that hundreds of thousands of people endured during the Soviet era.

‘How Much a Person Costs’ is the Russian title of Kersnovskaya's book of memoirs, written in the 1960s, but not first seen until the 1990s. “A man is really worth as much as his word is worth,” she answers her own question.

This amazing woman not only survived the Soviet labor camps, but also managed to go through the whole terrible experience with honor and dignity.

Kersnovskaya was born in 1908 in Odessa, then part of the Russian Empire. She had a noble origin. During the Civil War, her father was arrested, but then miraculously released. And the whole family fled by sea to Romania. In the 1920-1930s, they quietly lived in Romanian Bessarabia. Euphrosinia graduated from high school, received an excellent education and knew several languages.

On the family estate, she created an exemplary farm, worked in the fields herself and took care of the livestock.

The idyllic life ended in 1940, when Bessarabia became a part of the USSR: Soviet troops entered and repressions began. The prosperous peasants (‘kulaks’) were dispossessed and deported.

The Kersnovskys were evicted from their home. Euphrosinia sent her mother to Romania, but she herself stayed behind to take care of the household.

But soon, along with hundreds of Bessarabians, she was put on a freight car and taken to Siberia.

Kersnovskaya and her fellows were taken by train and then by barge down the river to a special settlement. While her mates were in despair, she seemed to feel optimistic: “After all, there was work ahead! And I was confident about everything concerning work.”

Back then, she did not yet realize that this was not work, but humiliating slave labor.

People were put in a cold barrack with bedbugs. They were not supplied with any utensils and were fed with 'balanda', a kind of thin soup made of scraps. And then, they were forced to work to exhaustion at the lumber mill.

A little later, Euphrosinia decided to take a bold step, to escape the camp. Better death in freedom than in captivity, she thought. For six months, the woman wandered through the wild Siberian taiga, nearly dying from hunger and frost.

However, eventually, Euphrosinia was captured and sentenced to another 10 years in a labor camp. Additionally, for imprudent words, she got another sentence.

“We had to stand in the water all day on the stone floor barefoot, almost naked, in just underwear, because there is nowhere to dry our clothes and it was impossible to take them off to dry them: the barracks were such a mess that they could steal our last footwraps,” Euphrosinia described the dire camp conditions.

But, the trials did not break her down. Several times, the now woman was transferred to different places. But, finally, she was sent to the Far North – to Norilsk, which had the most cruel conditions. There, Kersnovskaya volunteered to work in a coal mine, the hardest job. She was sure that this was the kind of work that would save her, and the “bosses” would be more kind to her.

Being a noblewoman, an intellectual and a person of honor, Kersnovskaya impressed with her courage and humanity. She fearlessly argued with the guards and with the camp “superiors”. She also tried to defend human rights not only for herself, but also for her fellow prisoners.

Perhaps, it was her non-Sovietness, her lack of habituation to the Soviet way of life, that helped her to survive and remain human. She refused to believe that everything was like that. She didn’t see the great purge of the 1930s.

Thus, while deportation the guards refused to give people water, even though the train was standing right by the lake. Euphrosinia was the only one who was not afraid to make a complaint. In addition to thirst, there were even more dire circumstances: a woman in a neighboring carriage gave birth and it was necessary to wash the baby. At night, Euphrosinia managed to open the bolt of the carriage with an umbrella and ran with a bucket to the lake. It cost her a jail cell and handcuffs.

More than once, she would refuse to compromise her principles. She would tell everything she thought right to the face of the investigators and camp bosses. And always tried to help those in need.

She never hid food, despite everyone in the Gulag doing that to survive. She would even share her bread ration with hungry people. On the day of liberation, she spent all the money she had received for work to buy pies for her brigade.

Kersnovskaya also helped bury the dead when the morgue staff could not cope; and she washed soldiers' laundry during World War II.

Euphrosyne was set free in 1952. But, she was restricted in her rights and could not move far from the place of detention. The then 44-year-old woman went back to work at the Norilsk mine, now voluntarily with the hope that she would soon retire, save some money and be able to live in peace.

Euphrosinia only met her mother again in 1958, after 18 years of separation. It was not easy: her mother lived in Romania and thought her daughter was dead.

They could only fully reunite in 1961 and when they finally did, they settled in a small house in Essentuki, the city in the Russian Caucasus. Now, there is a museum dedicated to Kersnovskaya.

Her mother was the main person in the life of Euphrosinia. And it was her to ask her daughter to write down about her life. So, Euphrosinia started in 1964 when her mother died.

Euphrosinia Kersnovskaya with her mother

Essentuki Local History MuseumIn the 1980s, her memoirs – several volumes of typewriting with illustrations – were distributed in 'samizdat', an underground Soviet self-publishing system. In 1990, the drawings were first published in the ‘Ogonyok’ magazine. And, very soon, the ‘British Observer’ also published them.

The full memoirs with illustrations were only printed in the 2000s and still haven’t been fully translated into English.

Russia Beyond is grateful to Igor Moiseevich Chapkovsky for his help in preparing this article.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox