G20 summit in China yields diplomatic windfall for Moscow

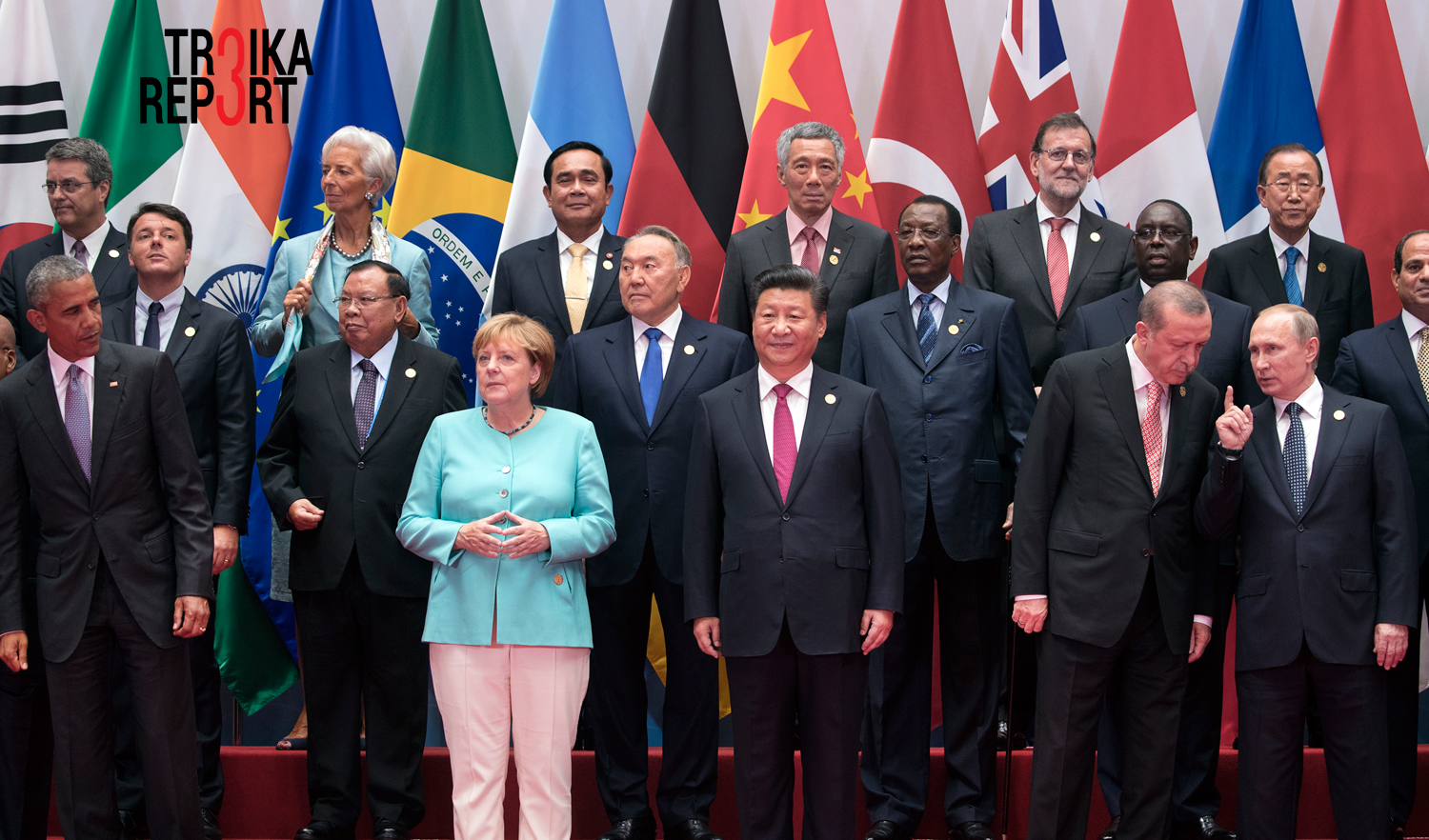

Summit leaders pose for a photo at the G20 summit hosted by China's President Xi Jinping center, in Hangzhou, China.

APThe meeting of world leaders in the Chinese city of Hangzhou on Sept. 4-5 has challenged the condescending view of G20 summits as routine photo opportunities with plenty of style but no substance. At least, Russian President Vladimir Putin refused to come home empty-handed – the one-on-one meetings held by the Russian president on the sidelines of the summit produced tangible positive results.

A biased selection of his interlocutors, predetermined by the gravity and complexity of bilateral relations, would probably focus on three key figures: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, UK Prime Minister Theresa May, and U.S. President Barack Obama.

Is Turkish Stream flowing again?

Following the recent reconciliation between Ankara and Moscow after a seven-month crisis in relations, the talks in Hangzhou with Turkish strongman Erdogan have highlighted at least five notable breakthroughs in the making.

Firstly, a joint Russian-Turkish investment fund could become operational as early as October or November, with credit lines offered to lucrative projects. Secondly, Moscow is winding down its food embargo against Ankara, thus reactivating the exports of Turkish agribusiness. Thirdly, the construction of the Akkuyu nuclear power plant in Turkey’s Mersin Province by Russia’s state nuclear agency Rosatom is due to be accelerated.

There is also the readiness of Erdogan’s government to finalize the re-registration of all previously issued permits for Turkish Stream, an offshore gas pipeline running across the Black Sea to the European part of Turkey. The first line may be completed by the end of 2019. Ankara has also showed an interest in shipping Gazprom’s gas to the border with Greece with the perspective of becoming a transit hub for deliveries to consumers in the European Union.

On top of all this, Russia and Turkey are close to an agreement on a free trade zone, capitalizing on an already drafted medium-term program for economic, technical and scientific cooperation.

Theresa May ‘does a Trump’

In a remarkable display of how to take a pragmatic approach to dealing with one’s diplomatic and political rivals, the new British Prime Minister Theresa May met Russian President Vladimir Putin for the first time and has committed herself to improving the almost non-existent relations between the two countries through dialogue.

“While I recognize there will be some differences between us, there are some complex and serious areas of concern and issues to discuss; I hope we will be able to have a frank and open relationship and dialogue,” May said.

The proverbial British understatement (“some differences between us”) is yet another celebration of the exquisite art of diplomacy that has fine-tuned non-aggressive verbal communications for centuries. In the context of the strained British-Russian relationship, it helps overcome a conflict of unmatchable interests.

“Doing a Trump” obviously falls short of a full “reset” but once again, as diplomats phrase it, this is a step in the right direction, is it not?

Zeroing in on a bargain over Syria

Moscow and Washington seem to be close to striking a compromise on the Syrian quagmire, though there are a few remaining “tough issues,” as U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry conceded.

However, it seems clear that Obama, now a “lame duck” with only two months left of his presidency to run, is keen to go down in the history books with some achievements on the foreign policy track that would portray him as someone truly worth of the Nobel Peace Prize he received in 2009 as a sort of advance payment for a yet unaccomplished deed.

Obama was frank about his skeptical attitude to the prospects of the cessation of hostilities in Syria. The outgoing U.S. president has good grounds to be doubtful. Washington is demanding that Moscow apply pressure on Damascus to stop targeting the so-called moderate opposition (pro-West militants?) and create a “humanitarian corridor” to Turkey through Syria’s northern regions.

Even if Moscow manages to convince and persuade Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad to call off air support of its ground forces, the anti-Assad opposition and Islamic State, which have been reinforced lately and are on the offensive, regaining lost territories, will not be tempted to respect the restraint possibly showed by the Syrian government.

The only end result of the implementation of the U.S. proposal might be a reversal of the tide in the civil war in Syria. Yet there are elements of this bargain in the pipeline that remain unknown for now.

The Kremlin turns its nose up at the G7

On the eve of the G20 meeting, German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier suggested inviting Russia to attend the next G7 summit provided there is enough progress in the resolution of crises in Ukraine and Syria.

In response, Putin's spokesperson Dmitry Peskov explained that Moscow gives preference to the G20 for the reason it “most fully reflects the line-up of forces and enables Russia to better display its potential in this format.”

Concurrently, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov reiterated that Moscow “is not clinging to the G8 format” and will not undertake initiatives to re-join this Western exclusive club.

Russia became a G7 “club member” in 1998, and back then it was considered a major achievement equal to the final burial of the Cold War hatchet and acceptance of the biggest chunk of the defunct USSR as a bona fide partner of the West.

Later, in 2014, the G7 blacklisted Russia and froze its membership in relation to the dramatic events in the east of Ukraine.

What has actually happened in the last two years to lead to such a cold-shouldered rebuff from Moscow to Steinmeier’s conditional invitation back into the fold? Why does Russia now favour the G20? Fyodor Shelov-Kovedyayev, an academic and former First Deputy Foreign Minister of Russia, provided his insight for RBTH.

“The G7 has largely overestimated its carrot and stick tactics regarding Russia. The G7 acted like a head teacher who would welcome a pupil at school one day and dismiss him or her back home the other. The G7’s behavior did not make Moscow feel welcome.”

– Some say the G20 lacks the eminent clout of stable democracies that is a hallmark of the G7.

“TheG20 is a platform for discussion and not so much for decision-making. For Moscow, it offers the chance to talk to major Western powers as well while reaching out to a wider audience.”

– Does this mean the G20 is nothing more than a discussion platform?

“Going back to the post-war period, it is noteworthy that Franklin D. Roosevelt suggested that only three superpowers have the right of passing ultimate decisions: the United States, Great Britain, and the USSR. Stalin then successfully pressed for France and China to be included into the UN Security Council, consisting of five permanent member states. He believed that it would deprive the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ duo of the ability to dominate. Stalin hoped that China’s leader would simply echo his words, and France would be cooperative due to [its] gratitude for defeating Nazi Germany.”

– Do you believe the UN Security Council is still in demand to manage the world order?

“…or manage world disorder. For the moment, yes, this is the best tool at our disposal. But the world is changing, and its fundamental pillars are no longer untouchable.”

– Is there a privileged place reserved for the G20, as of today?

“New actors have entered the diplomatic fray amid a dynamic upgrade of the technological basis: transnational corporations, professional associations, mass media, etc. At the same time, the death rites for nation states turned out to be premature. No one knows what the future configuration of international institutions focused on global governance will be.”

A pragmatic voice

It would be no surprise that Russia, which produces only 3 percent of global GDP, is often considered a minor player in this premier league.

Nevertheless, Moscow can list as its contribution to global “perestroika” the so-far symbolic link-up between the Chinese One Belt, One Road initiative with the Eurasian Economic Union, the concept of a North-South logistics corridor, and a legal basis for the intensified cooperation of the Caspian basin nations, among others.

Furthermore, aggregating certain competitive edges (airspace technologies, nuclear power generation, 15 percent of global grain market share, an efficient armed forces – as demonstrated recently in Syria – and a pragmatic pro-active diplomacy), Russia is accepted within the G20 as an equal and worthy partner in re-shaping the world order.

A lot depends on whether the G20 is part of the problem in constructing a new world order, or part of a solution.

Disharmony in the G20: What’s next?

Chinese President Xi Jinping, the host of the Hangzhou G20 summit, attempted to subordinate the plenary meetings solely to the convulsions of the global economy due to feeble growth in demand, rising protectionist barriers, and turbulence on the financial markets.

However, his call for pro-active monetary and fiscal policies coupled with structural reforms to ensure “sustainable, balanced and inclusive growth” would hardly have any leverage in the absence of a consensus among the G20 nations on who must compromise first.

Disputes are abundant. China is accusing Australia of blocking the $7.7 billion sale of the country's biggest energy grid to Chinese bidders last month, which comes in the wake of a similar fit of renascent protectionism when a China-led consortium was prevented from buying Australian cattle company Kidman & Co.

In turn, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker blamed China for an “industrial overcapacity” that has wiped out many jobs in the EU steel industry. Finally, the United States has recently imposed 522 percent duties on cold-rolled steel made in China, claiming it was an adequate response to dumping tactics.

Unfortunately, with the U.S. and the “Anglo-Saxon” alliance fixed on two trade blocs embracing countries of the Pacific Rim and the European Union (both excluding China), the chances of giving more powers to the G20 to manage global economy are so slim as to be practically anorexic.

The next G20 summit in Hamburg is most likely to be focused on the “immigration crisis” and for this reason the idea of empowering the institution to manage global economic crisis will not be high on the agenda, if at all.

By and large, the actual balance of interests within the G20 spells doom for the prospect of fulfilling President’s Xi grand Chinese dream. “We should turn the G20 group into an action team, instead of a talk shop,” said Xi. Yet judging by his look at the moment, Xi hardly believes in the feasibility of his proposal.

Special section: Troika Report>>>

Read more: What are Russia's objectives in the Middle East and in the Caspian?

The opinion of the writer may not necessarily reflect the position of RBTH or its staff.

Subscribe and get RBTH best stories every Wednesday

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox