Olga Kozlova, a 57-year-old blonde of medium height with an impossibly slim figure for her age, sits in a small two-room apartment at a wooden table bedecked with a white tablecloth. On the edge stands a small, permanently-on TV set, and a plate of cheese (probably Roquefort), an aromatic candle, and a laptop all within reach. Meet my mother.

From morning till late evening, she works in an insurance company. When at home, she watches Game of Thrones. She hasn’t seen the last season yet, but has read all the spoilers, so she’s upset and demanding that I find a new series.

“What about Chernobyl?” I suggest, pushing Lucky, our overly active white husky, away from the cheese.

“Saw it all in Pripyat. I remember now, I went there after the accident...”

“WHAT?!”

“You never listen to me, I already told you!”

It is August 1986. Mom steps off the train at Melitopol railway station (1,100 km from Moscow). She is 24 and a few years ago graduated from the Institute of Communications and Computer Science with a degree in engineering. She works for the Moscow city telephone service, and spends her vacation on the Sea of Azov.

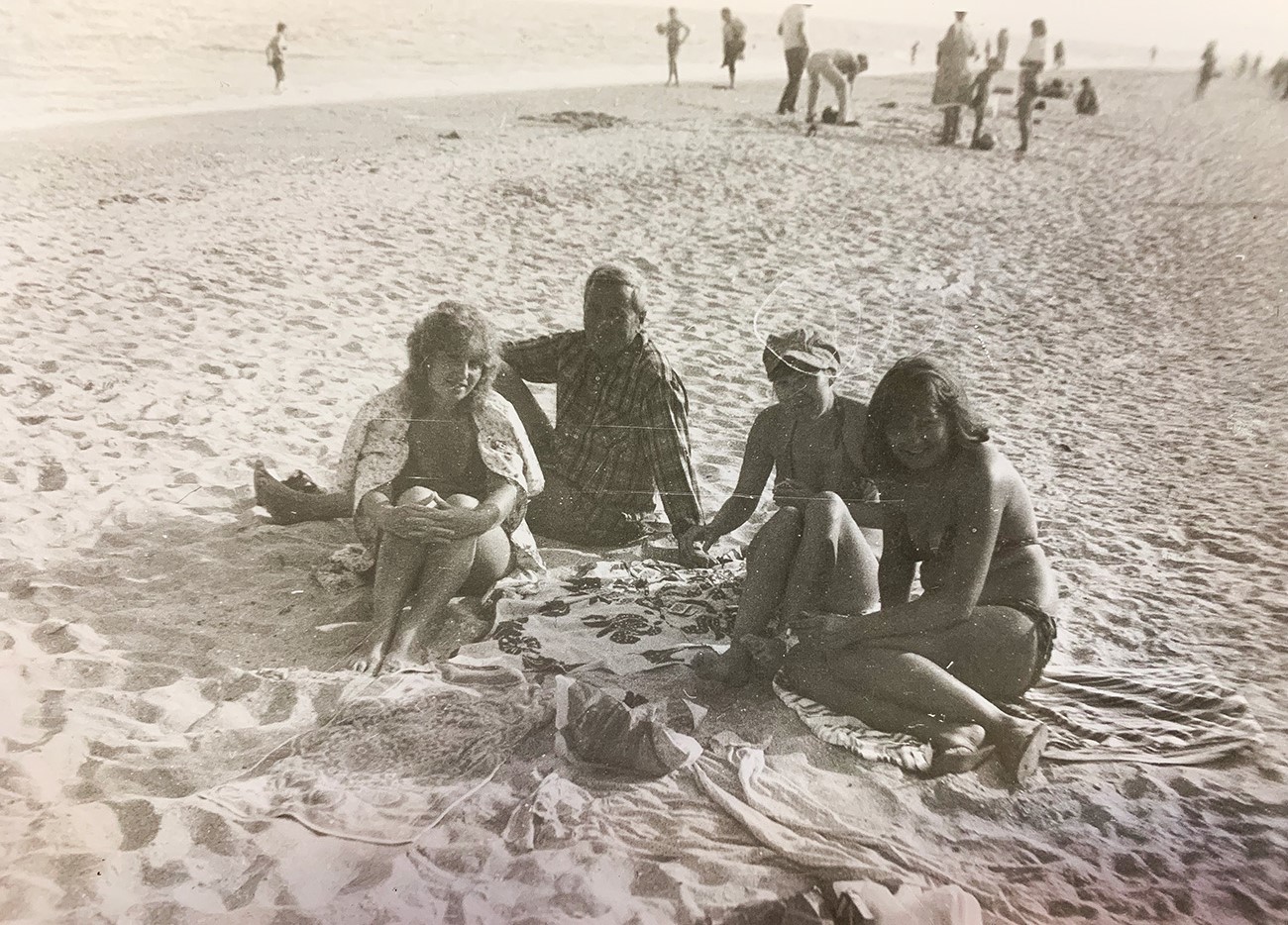

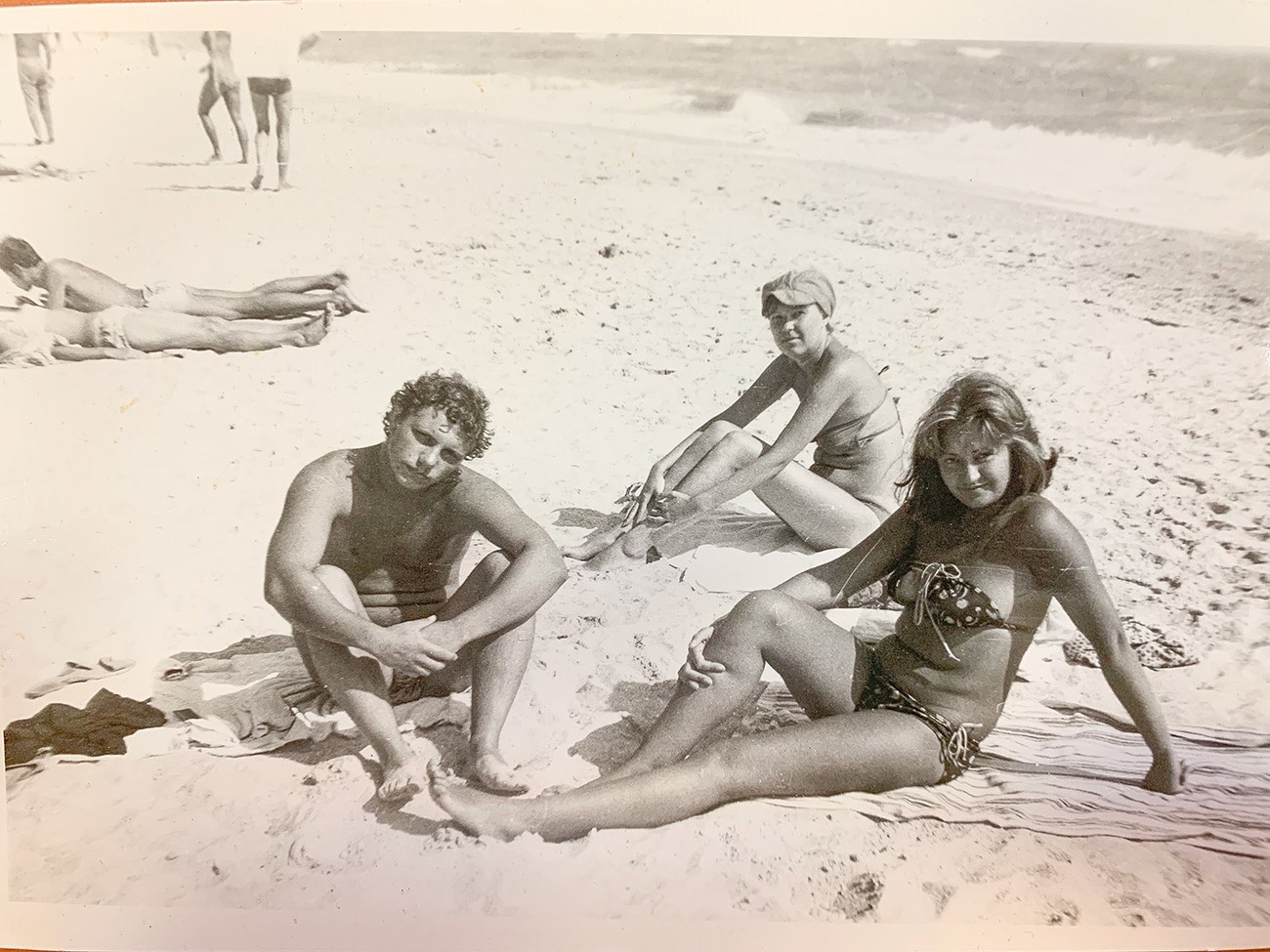

With her on the platform are several middle-aged and pre-retirement couples, plus a tall, fair-haired lad, looking as if he’s just had a perm, and a tall chestnut-haired woman of about 30.

“I immediately made friends with that girl, Ira. She said she’d come to Ukraine to find a fiancé, but everywhere there were just couples. The guy Alexei was only 18, still at college studying to be a dentist,” my mother recalls.

A tall gray-haired pleasant-looking man of about 50 approaches the group with suitcases and backpacks. He turns out to be Ostap, the tour guide. What Ostap does besides giving tours is of no interest to my mother.

“He put us all in a small bus and drove to a village near Melitopol. There we stayed in small wooden huts rented out by locals. There were three people to a room, but it was cheap and cheerful,” she continues.

The first week of the trip was relaxed. Ostap sometimes took us on excursions around Ukraine, we drank wine in the evenings and went swimming. One thing caught my mother’s attention – in some places along the coast there were signs saying that swimming was prohibited from 16:00 to 20:00.

“I asked Ostap why, and he said ‘radiation, but all’s well’ and laughed. I was wary, but not overly so,” she says.

“Are you ready, children? “Yes captain!” With unanimous childish delight, the group unhesitatingly agrees to Ostap’s proposal to visit “the one and only Chernobyl.”

“Sure, everyone knew about the accident. But I was sure the radiation would have no effect on me. For us back then, the word ‘Chernobyl’ sounded distant somehow. So what if it exploded, things do,” mom recalls.

The journey from Melitopol to Pripyat (a town 3 km from the nuclear plant where the accident occurred) was about 850 km by car. This August day in 1986 is hot, a little over 30 C. Mom recounts that the group had armed itself with bottles of wine in advance, so all she remembers of the way there are the canteen stop and the “Contaminated” signs. They had no protective gear, only summer clothes.

Approaching 7pm, the bus stops in the forestland near the Pripyat River. Ostap climbs out holding a bottle of wine in one hand and a Geiger counter in the other.

The whole tour lasts about two hours – the group strolls through the forest, taking photos.

“Many of the trees and bushes seemed unnaturally bright and fresh, although it hadn’t rained for a long time. The roofs of already abandoned buildings were visible from afar, nothing more,” mom shares her impressions.

Suddenly a fly lands on her hand. Looking back today, mom claims it was half the size of her palm.

“Yes, if you encounter mutants, don’t be alarmed,” jokes Ostap. Everyone laughs and starts looking for mutant insects. Someone is trying to pick leaves from the trees, which is not allowed. Having found nothing more of interest, the tourists ask to be taken to the city itself.

In response, the guide glances at the Geiger counter. A second later, as if suddenly sobered up, he commands in a businesslike manner: “All aboard, excursion’s over!” Everyone grumbles, but having stopped for a smoke and a group photo for keepsakes, they slowly get on the bus.

A couple of months later, back in Moscow, my mother felt an unbearable pain in her lower abdomen. She then got a phone call from Alexei and Ira – he was suffering from similar pains, while she complained of constant weakness and dizziness. Other people from the tour also phoned to complain of pain and to offer advice, but she no longer remembers their names.

“The diagnosis took ten days. At first, they thought it was appendicitis, but it turned out to be appendagitis [inflammation of the appendages],” she says.

Alexei really did have appendicitis as it happened.

“As a dentist, he diagnosed himself and went to the hospital. He wasn’t wrong,” mom recalls.

Irina, it transpired, was on the verge of cancer. The doctors found an increased number of leukocytes in her bloodstream, and she was given an emergency blood transfusion. All three successfully recovered, although it took mom at least three months. She knows nothing of the fate of the other tour participants.

“Can you imagine, I was even advised to get pregnant – they said it was the best way to prevent the inflammation,” she recalls.

“But you did tell the doctors you’d just been to Chernobyl, didn’t you?” I say indignantly, glad to have been born ten years afterwards.

“No, why? I told you it was just an ordinary tour, you never listen to me! Only my parents went off on a rant when they found out.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox