In an ordinary Moscow apartment, a guy and a girl sit on a sofa. Both are no more than 16 years old. In the air hangs the faint smell of white wine and awkwardness. In the guy’s ear is a wireless earpiece – his father and friends are observing the couple via hidden cameras and giving advice about when to make a move. But just before he plants a kiss, the line suddenly goes dead – one of the “helpers” has spilled coffee on the equipment. The son is forced to go it alone.

When the connection is re-established, we see the same girl, but now wearing a veil and wedding dress. Her boyfriend (also the same as before) is holding her hand looking like a rabbit caught in the headlights – a clear hint that the girl eventually got pregnant, and the guy, being a “proper gentleman,” had to marry her.

It’s a clip from a joint video by Russian rap group Kasta and Latvian rock band Brainstorm for their song “About Sex,” which urges parents to pay attention to their kids’ sexual education to avoid waking up one morning to an unplanned pregnancy and a divorce-doomed shotgun wedding.

There are no recommended materials for sex education in Russia, save for a short chapter in a textbook about general health and welfare for eleventh graders. Instead, school students’ knowledge about relationships, contraceptives, and the risks of unprotected sex is drawn from such founts of wisdom as commercials, movies, video games, pornography, and – most terrifying of all – classmates.

At the same time, children are embarrassed about asking their parents, who in turn are more than happy to shift responsibility for birds-and-the-bees conversations to teachers. According to a poll by the All-Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM), more than 60% of Russians support the introduction of sex education in schools.

In Soviet times, too, the topic was off the school curriculum, although a chapter on the reproductive process did appear in anatomy textbooks in 1986.

In 2014, the State Duma approved the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which provides for the introduction of sex education in schools. As yet, there are still no training courses, and the government as a whole cannot reach a common opinion on the issue. Deputy Prime Minister Tatyana Golikova has said that contraception should be taught at school, but Education Minister Olga Vasilyeva and Children’s Ombudsman Anna Kuznetsova do not support the idea.

The introduction of sex education classes also complicates the 2012 law “On Protecting Children from Information Harmful to Their Health and Development,” which prohibits the depiction and description of acts of a sexual nature to children under the age of 16. It could potentially work against teachers, but some are not averse to risk-taking.

Two years ago, 34-year-old English teacher Svetlana gave an after-school lesson about HIV to eighth graders. During the conversation, it turned out that almost half the class was sexually active, but no one used condoms.

“To my astonishment, they said they were too ashamed to buy them. I burst out: ‘You’re OK with buying cigarettes and alcohol [illegal to sell to children in Russia under 18], but not condoms [no age restrictions]?’ Everyone replied in unison: ‘Yes,’” she recalls.

After that, Svetlana held a separate conversation with the female half of the class about contraceptive methods and abortions. And she had no intention of asking their parents for permission to do so.

“We rarely contact parents and still less complain about the children, because you don’t know what might happen. One time, we found out that a boy whose teachers had complained about was beaten by his father and locked in a cellar. Since then, we try to solve problems without parents,” she says ruefully.

Daria, a physics teacher from Moscow, acknowledges that sometimes even children from well-off families lack basic knowledge.

“Some girls don’t know that menstruation and urine come from different parts of the body; they don’t know about tampons or what the hymen is. Boys are embarrassed about wet dreams and erections,” she opines.

In her view, Russian biology textbooks only cover the reproductive system and HIV in very general terms. And in any case, many teachers prefer to skip these chapters altogether.

Alexandra Sotova, a 25-year-old cashier from Volokolamsk, is due to give birth to her first child, a girl, in August this year. She would like her daughter’s sex education to be different from hers.

“We were basically told that a girl could get pregnant by touch,” she states.

She was properly informed about contraception only in college, but by age 16 it was no longer relevant to everyone, since there were 2-3 pregnant students in each group.

Some schools even invite priests to give talks on morality, says 26-year-old speech therapist Tatiana Gribanova.

“There were two representatives: a priest and his wife. They told the girls not to wear trousers because they rub the labia and cause women’s diseases,” Tatiana recalls.

Students were also told that biological information about all previous sexual partners of a woman is transmitted to her child. The following example was used to illustrate the point: “If you try to cross a mare with a zebra, and then the same mare with a stallion, the result will be striped foals.”

It is unacceptable for priests to share their personal, “pseudoscientific” points of view without the consent of the diocese, asserts Alexander Volkov, head of the press service of Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia.

“Such statements do not correspond to the official position of the Church. They are the private views of individuals. In such cases, parents are fully entitled to complain to the school administration or the diocese,” he says.

Moreover, visits by clergy are permitted only with the consent of the school administration itself.

“Schools often ask for help with teaching such topics. They sometimes don’t know how to broach ethical and moral issues with the children they encounter on a daily basis,” explains Volkov.

Sex education can damage a child’s psyche. This is the first line of attack from opponents of such lessons in schools.

Second, some teachers and parents consider the topic too intimate for discussion outside the family unit.

“We somehow managed to learn everything without such lessons, so today’s children can do the same,” is the third most common argument.

Forty-year-old Alexei, a father of a ten-year-old daughter, got his sex education from erotic films, adult magazines, and Christian literature for children.

“Our generation turned out all right. And today’s children are smarter than us, especially with their ‘internets,’” he believes.

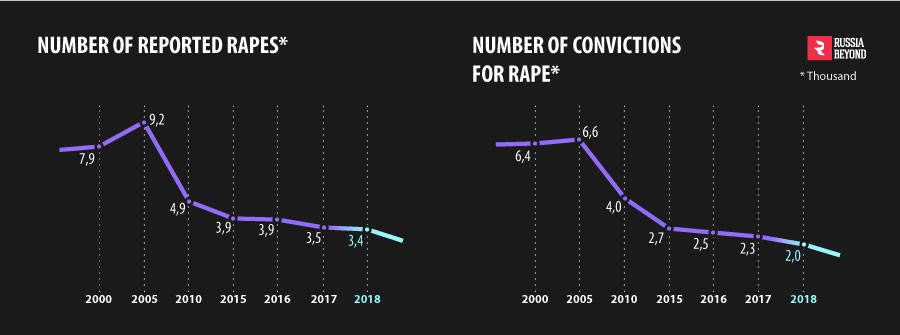

While it’s hard to tell which generation is smarter – parents with their video tapes or children with the Internet, it’s harder still to count how many victims of sexual violence there are in Russia, and how many minors are among them. Headlines such as “Teenagers film schoolgirl being raped with a marker pen” or “Two men rape underage girls” appear almost daily in the Russian media.

While some argue about the need to introduce sex education in schools, activists have long taken the campaign online.

For instance, UNESCO started the Dvor (Yard) community in the Russian social network Vkontakte. There, using memes, they share helpful advice about contraceptives, relationships, and ways to deal with depression.

According to Alexandra Ilieva of the UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education, sex education is not only about contraceptives and personal hygiene, but about how to protect oneself from violence from the opposite sex.

“It’s important for teenagers to learn not only about physiology, but how to say no and who to turn to for help if they feel pressured,” says Ilieva.

Alexandra regrets that the group is attended by almost no adults. She is sure that parents and teachers would also benefit from reading and digesting the information, for them to then pass on to their children and students.

Sex education is starting to become a topic for Russian vloggers, too. Tatiana Mingalimova, who usually interviews pop stars on her YouTube channel, launched the “Friends” project, in which she and a group of female buddies sit in a bar and discuss the first time they had sex, types of orgasms, and the do’s and don’ts of foreplay.

All this is discussed during special sessions and lectures for adults, says Yana Zadorozhnaya, a PR expert for the “Kinky Russia” online community. She says that sexual technique is far from being the main topic.

“First and foremost, we teach the culture of sex, including protection and mutual consent. After all, adults themselves need to learn something before they can instruct children,” says Yana, and it’s hard not to agree with her.

READ MORE: What were Russian kids in the 20th century told about sex?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox