Many Russians from older generations have fond memories of the free vacation vouchers that Soviet citizens used to receive from their employers. These vouchers allowed them to stay for up to four weeks at holiday hotels or health resorts at which guests were provided with full board, went on excursions and enjoyed late-night discos. Other people recall that the most they could hope for was to visit relatives in the country, while a beach holiday remained beyond their wildest dreams. For them, swimming in a river, fishing and weeding one's garden were the only available pleasures. So how did ordinary Soviet people spend their vacations?

Bathers enjoy a sunny day at the Brigantina holiday centre in Anapa, Krasnodar Territory, 1982

Boris Kavashkin/TASSGenerally speaking, in Russia the concept of paid annual leave was only introduced in 1918. Until 1967, the annual leave allowance was just 12 working days, but it was later raised to 15 (nowadays it is 28 calendar days, or 20 work days). Some people were entitled to longer leave though. For example, if a person worked in the Far North their leave allowance was 45 working days. For those working in educational institutions the leave allowance varied from 24 to 48 working days. People employed in hazardous industries got 36 working days. Before going on leave, everybody received so-called vacation pay, i.e. their average pay for the time they would be on leave plus pay for the days of the month that they had already worked. Thus, vacation pay for a two to three-week holiday was often as much as a person's full monthly salary. Of course, most people preferred to holiday in the summer. So, what could they afford?

In Soviet times, there were numerous health resorts all over the country where people spent their holidays and received medical treatment. In the 1970s, there were thousands of these in Krasnodar Territory, Crimea, Abkhazia, Altay, and on Lake Baikal.

Livadia sanatorium (former tsar palace) in Crimea

Vladimir Vdovin/SputnikVisitors to these health resorts were given a full medical checkup, prescribed a special diet and provided with entertainment each evening. In effect, this was the Soviet version of an all-inclusive resort where holidaymakers practically did not have to spend any more money on anything else.

Radon baths at Kirov sanatorium in Pyatigorsk, the North Caucasus

V. Kuzmin/SputnikDepending on the resort, a holiday voucher for a three-week stay at a health resort by the sea cost 160-220 rubles (the average monthly salary was around 170 rubles), while a voucher to a holiday hotel without any medical treatment cost around 40 rubles. Hardly anyone had to pay the full price though. Usually workers paid only a third of the full amount, while pensioners, veterans and single mothers received holiday vouchers for free.

Visitors consult with a nutritionist in the sanatorium of the Moscow Serp i Molot Steel Plant, 1981

Yuri Lizunov/TASSBen Elmann shared the following childhood memories: "I went to Anapa in September 1986, to a holiday hotel named after Eugenie Cotton, with my father on a voucher he had received from his trade union. I was about 14 at the time. It was like a Soviet version of an all-inclusive holiday: the voucher included two beds in a room for four people, four meals a day, and a medical checkup upon arrival, after which various medical procedures were appointed. I can't remember whether our room had a toilet, but it definitely did not have either a bath or a shower. Everybody washed in a shared bathhouse. The food was very good, and there was always the opportunity to choose between several dishes. The buildings of the holiday hotel, as far as I remember, were located almost by the sea. There were no problems with finding a place on the beach.”

Holiday-makers relaxing on the beach of the Tikhy Don sanatorium for several collective farms

Yakov Ryumkin/SputnikGetting a holiday voucher to a place like that was rather difficult though, especially if the resort was in Sochi or Yalta. Each enterprise was allocated a certain number of holiday vouchers, and there was a waiting list to get one.

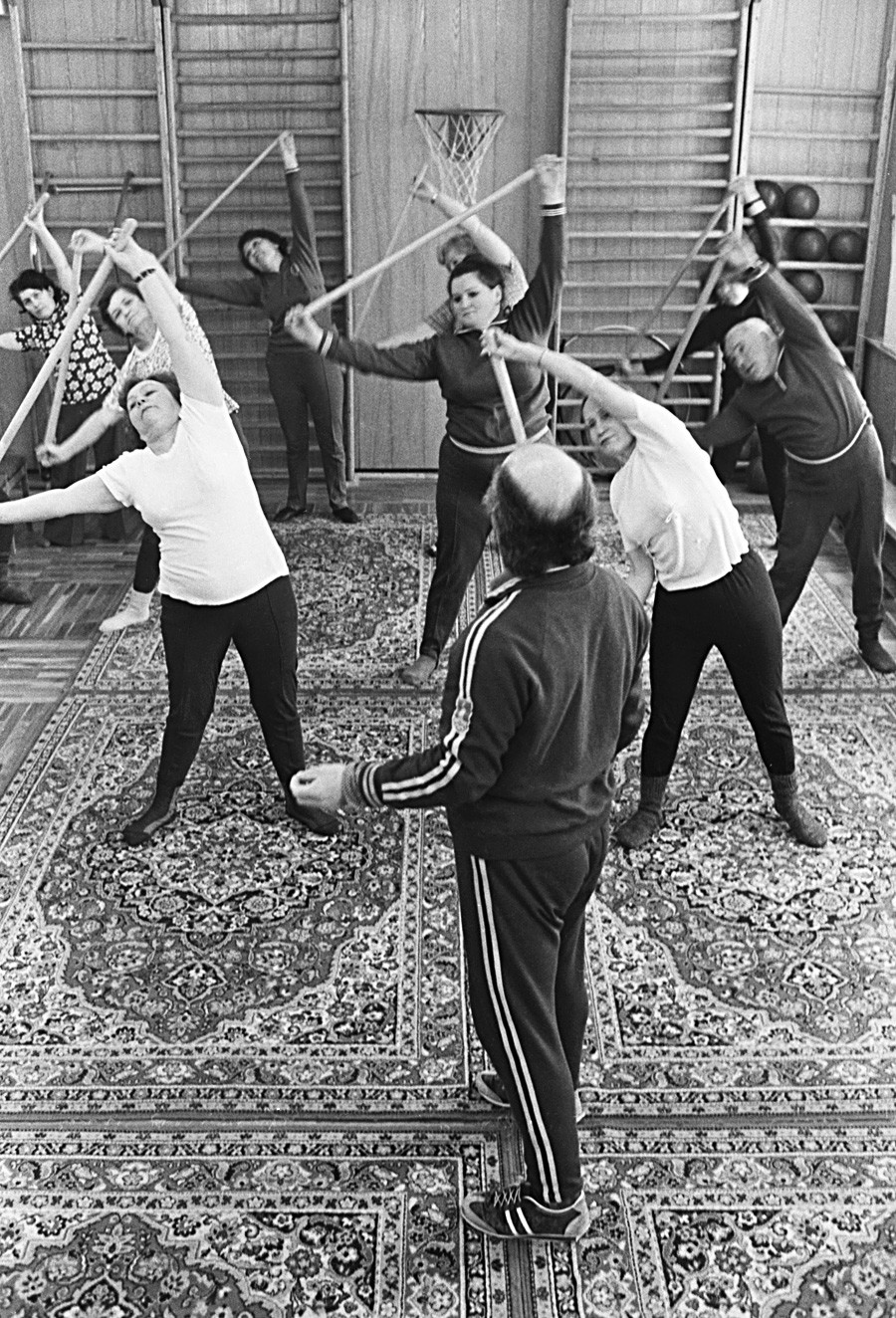

Physical therapy in a Soviet sanatorium, 1981

Viktor Koshevoi/TASSAn ordinary employee could only expect to receive a summer vacation voucher once every few years. Additionally, vacationers had to share rooms with each other, and there was no way of knowing whom you would end up sharing a room with. Many of these health resorts have since been converted into ordinary hotels and charge far higher prices now.

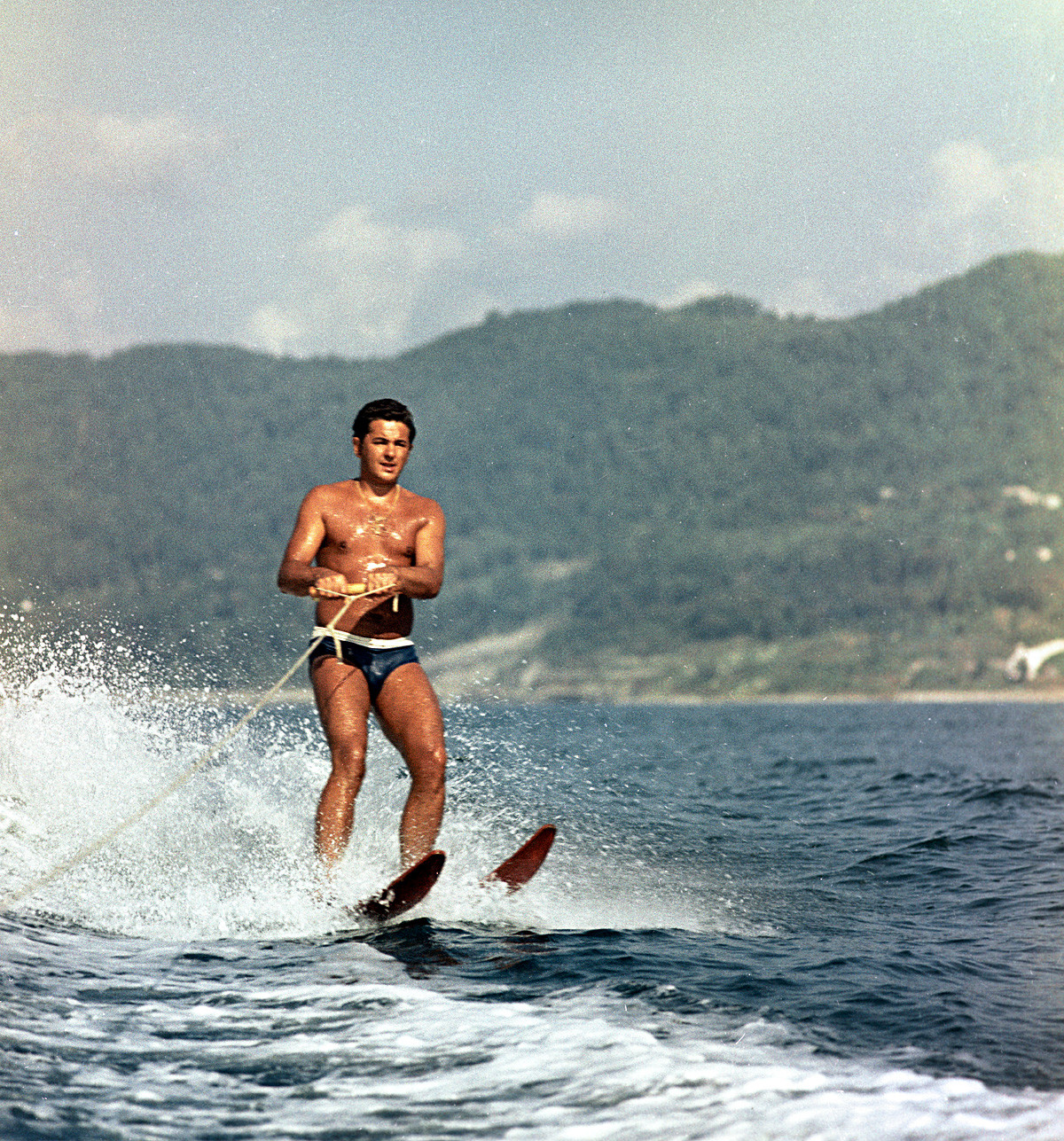

Some people made the way to the sea on their own if they could manage to buy a train or plane ticket. The most popular destinations were the southern coast of Crimea (Alushta, Yalta), Sochi, Anapa and Abkhazia.

Camping on the Black Sea shore

Sergey Smetanin/SputnikAccommodation was rented from local residents. In the past, there were not as many hostels and hotels as today, and prices were relatively cheap. For example, in Crimea in the 1970s, a bed cost from 1 to 3 rubles per day. Some lucky married couples managed to rent a whole room for themselves, while single travelers often had to share a room with strangers.

Diana from St. Petersburg recalls the following experience: “I went to the Black Sea, to Sevastopol, twice, with my aunt. We rented accommodation from local residents and bought third-class train tickets (my aunt was a teacher, my mother, an engineer, she also received a pension for my dad, who was a military man and had been killed). We also holidayed in Jurmala with my mother, also renting accommodation from locals. It was easier for people from St. Petersburg to rent a room there as they were considered cultured people, so local residents would often meet trains from Leningrad. In Jurmala, rooms cost up to 7 rubles a day, I seem to remember.”

A holiday at the Black Sea

Oleg Ivanov/SputnikIf a person had a car—a rarity during Soviet times—that resolved how they spent their holidays. They packed up a tent, a cooking pot and two weeks' worth of food supplies into their Lada or Volga, and the whole family drove south.

Elena, who is from Moscow but now lives in Prague, wrote down her memories: “When we went on holiday by car, we took with us as much non-perishable food as we could: cans, cereals, dry sausage... I think we even melted butter and took it with us in a jar. And we always took toilet paper. If you forgot it, that was that: the chances of buying it anywhere on the road were nil."

Camping in Kostroma Region, 1976

Sergei Metelitsa/TASSPeople who travelled to sea resorts independently cooked themselves or ate at canteens. A kebab cost 75 kopecks, while dinner for two at a restaurant could set you back 10 rubles. Recreational pastimes included renting a boat for around 40-50 kopecks an hour, amusement parks rides for 50 kopecks or boat trips for 1.5 rubles. Tourists often brought fruits and berries back with them from the south. Sometimes they even made jam right at the resorts…

According to the TASS news agency, in 1968 Crimea received 3 million independent travellers and 1 million tourists with holiday vouchers, whereas in 1988 the figures were 6 and 2 million respectively.

Overall, by 1991 health resorts all over the Soviet Union could accommodate 1.3 million people, while the entire population in 1986 stood at 286 million.

The popular blogger Germanych touched on the exclusivity of seaside holidays: “Among my relatives, far from everybody had been to the Black Sea (or indeed to the Azov or Caspian seas either). Among my classmates (and therefore their parents), too, far from everyone had been to the sea. When I served in the army, especially in Siberia, I don’t think any of my fellow servicemen had ever been to the sea.”

Dacha time, 1986

N.Zheludovich/TASSIn other words, not everyone could afford an independent trip to the sea or a holiday camp. If teenagers or students were unable to attend a summer camp, adults most often chose the least expensive option, which meant going to the country. Not many people had dachas of their own, but almost everyone had relatives who lived in the country. They could visit them and spend their time weeding their hosts' kitchen gardens, bathing in a local pond and fishing.

Another popular option was to rent a dacha for the summer. This could be quite inexpensive and often consisted of renting just a terrace or a couple of rooms in the house. The price depended on its distance from large cities and how accessible it was by transport. But, of course, no matter how big or small the dacha was, it was guaranteed to be without running water or toilets—these facilities were located outside.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox