Arshak Makichyan is a 25 year old violinist who has just graduated from the prestigious Moscow State Conservatory. He’s also a young activist who knows he cannot save the world by playing the violin. Last weekend was his 28th week of striking in a row to demand urgent action on climate change. Every Friday since the Global Climate Strike for Future, Arshak has been holding a single picket in the middle of Pushkin Square in Central Moscow.

On the first day of the Global Week for Future (September 20-27, 2019), some 4 million people in 150 countries took to the streets for the biggest global climate strike to date to demand urgent action on climate change. One of the key movements in this strike is Fridays For Future, also known as the School Strike For Climate, which was started by one, now very famous, young Swedish girl in August, 2018. She’s a household name now. Inspired by Greta Thunberg, school children and students around the world have begun skipping school on certain days to demand 100% clean energy and keeping fossil fuels in the ground.

Arshak Makichyan. Striking for the climate

Zhanna IsmailovaWhile last weekend’s climate strikes were the biggest to date, in St. Petersburg, only 100 young people came out and in Moscow and Novosibirsk that number was even less (around 30-40), according to Konstantin Fomin, the press officer for Greenpeace Russia. Even though the numbers are humble, at least, Arshak Makichyan is not alone anymore, becoming Russia’s own Greta Thunberg: he has inspired young people in Irkutsk, Kaliningrad, Kursk, Novosibirsk, Nizhny Novgorod, Sochi and other cities across Russia, to come out and demand a clean, safe and habitable future.

“The main problem in Russia is that there is so little information in the mass media about the climate crisis, as well as the youth movements like Extinction Rebellion and FridaysForFuture that are fighting for their future,” Arshak explained to Russia Beyond.

Irina Kozlovskikh, a specialist at Greenpeace Russia’s “Zero Waste” project, also believes that one of the greatest obstacles to the growth of this movement in Russia is a serious gap in knowledge among the Russian public about the causes and effects of global warming.

“According to recent studies, ecological problems are in the top three concerns for many Russians. But to most Russians, ecological problems are usually limited to dumps and air quality… in some parts of Russia the construction of waste incinerators is also a very serious concern. Climate change, however, is still a very abstract concept for the majority of Russians and its consequences are something that’s quite difficult to measure on a day-to-day basis. When people in Russia hear the phrase “ecological catastrophe” they imagine tornadoes, typhoons, forest fires, etc. Climate change is something that is happening gradually, but we’re beginning to feel the consequences more and more as time goes by and nothing is done,” Irina explained.

Arshak’s despair that no one is doing anything about this in Russia soon turned into determination to start doing something about the situation and to bring the urgency of this global crisis to the spotlight in his country. “The most important thing to do now is to stop shutting up the truth and to explain just how dire the climate emergency is. As soon as people find out the truth we’ll find a solution. Together,” he said.

According to Chingis Balbarov, social media coordinator at WWF Russia, Russian youth are ramping up their fight for things like clean air and clean water, as part of the broader battle for their rights. After all, they are the ones that are inheriting the planet with its rapidly deteriorating environmental conditions from the previous generations. If the government keeps ignoring their demands, they will start taking to the streets more actively, the expert told Russia Beyond.

However, the situation with organizing rallies and mass gatherings is legally quite complex in Russia – especially for young people. Those under the age of 18 are not allowed by law to organize mass protests or even hold single pickets.

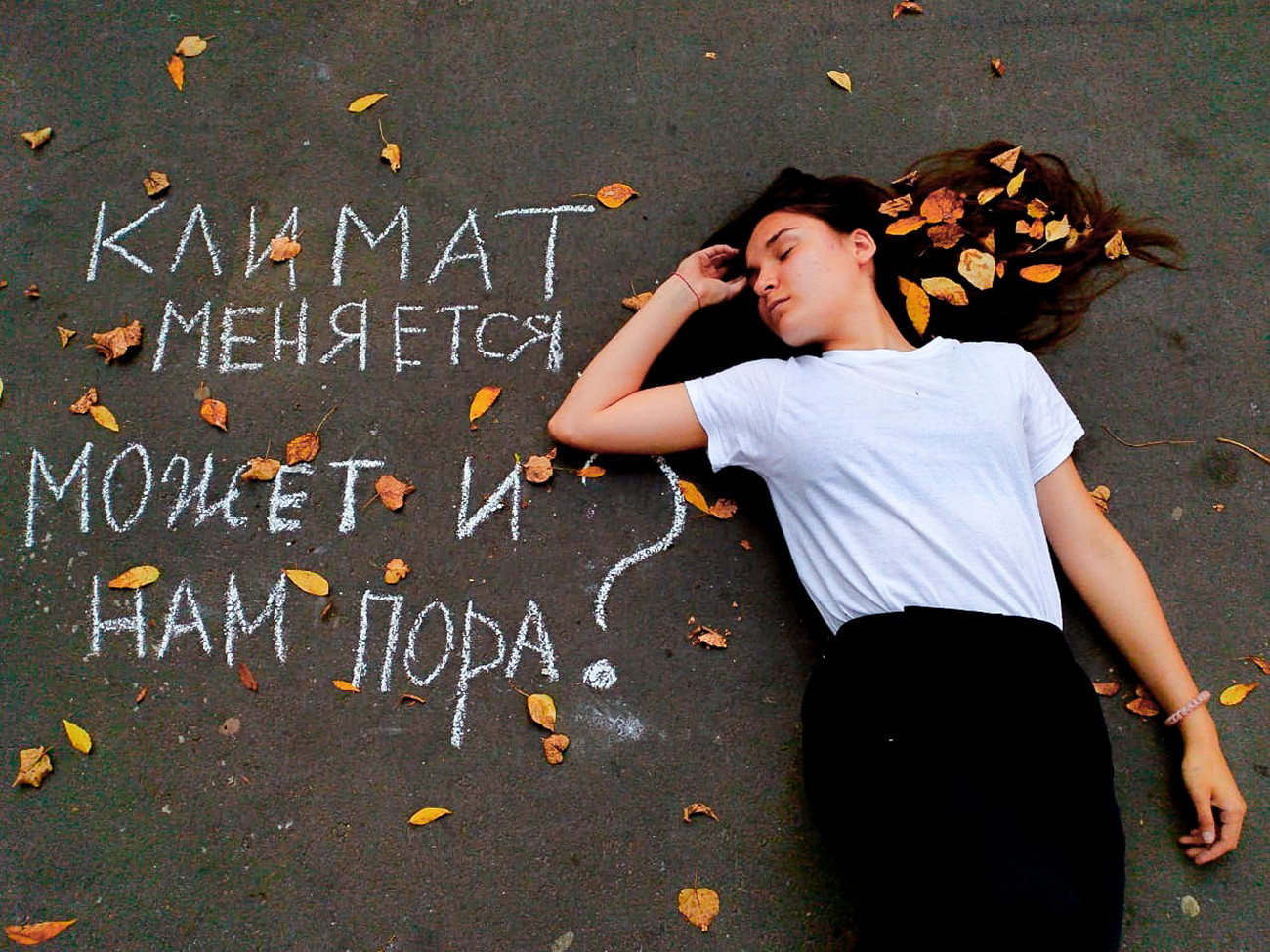

Karina Kuznetsova: The climate is changing. Maybe we should too

Personal ArchiveSome of the activists are not being stopped by these limitations. In the small town of Gus’-Khrustalny, 16 year old high school student Karina Kuznetsova is the only one who comes out on Fridays to strike for her future. She remembers her first picket protest like it was yesterday: “It was scary. In a town as small as ours where everyone knows each other, it is a brave thing to do. I’m thankful that one friend accompanied me for moral support. But it went well, people had different reactions: some smiled as they walked by, got into a discussion or asked me why the planet is dying.”

Karina Kuznetsova: Our planet is dying, but we don't talk about it

Personal ArchiveAdditionally, it is often a cumbersome task to coordinate a rally or protest with local authorities and get the necessary permissions. In Moscow, Arshak’s requests to hold rallies are either denied and the only place he is allowed to gather people is the so-called “Hyde Park”, a remote part of Moscow’s Sokolniki Park, which sees virtually no passers by.

Looking at how far the Russian branch of Fridays For Future has come since Arshak began his single pickets in March, Konstantin Fomin thinks the movement does have a future in Russia: “The breakthrough movement for Fridays For Future in Russia happened in May [2019], when Moscow authorities finally approved two groups. In the past two weeks, we’ve observed a growth in numbers of young Russians joining the movement – possibly because people heard Greta’s speech at the UN General Assembly and saw the huge global turnout for the latest Climate Strike.”

Greenpeace Russia action next to the House of Government (the Russian White House)

Greenpeace RussiaOne such person is Ksenia Stadnikova, 25, an IT specialist from Nizhny Novgorod. Already last year, Ksenia noticed news about Greta Thunberg and her School Strike for Climate movement. In March, she learned of climate strikes that took place in several Russian cities. She immediately went on fridaysforfuture.org to see if there were any events planned for Nizhny Novgorod, but instead saw that Russia was one big empty spot compared to the rest of the world. By that time, some 2 million had already come out to strike for climate action worldwide. Ksenia offered to organize an event herself. Together with some other local activists they submitted a notice and held their first picket in the city center on May 24.

“I felt a sense of danger, especially after detentions of peaceful protesters in other cities across Russia. But all went smoothly: 13 people came together and managed to attract the attention of passers by. We also held these ‘mass’ pickets on July 12 and September 20,” Ksenia recounted.

Irina Kozlovskikh, who participated in several Friday for Future rallies in Moscow and Kaliningrad, said she was surprised by the amount of young – “really young” – people who came to speak out. She said she was inspired that these Russian youngsters all knew the intricacies of the Paris Climate Agreement, were very aware of the extreme environmental damage caused by animal agriculture and were up to date on the latest scientific findings in general.

Irina Kozlovskikh: I want to be like Greta when I grow up

Personal Archive“It’s important that young people keep attending these protests to show that it’s not something scary, that these events do stay within legal boundaries and there is no reason for detainment or arrest. We need to keep talking about positive examples from other countries, like Australia, where 300,000 young people came out to strike last week, or in Berlin where 270,000 came out and, in total, 4 million worldwide. We need to keep repeating that if we don’t slow down the pace of global warming we, the human race, simply won’t have a future on this planet,” she concludes.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox