For years, émigrés were the main source of the most prevalent anti-Soviet, and then anti-Russian, myths. Emigration from the Soviet Union was one-way. On exit, you were stripped of your Soviet citizenship, and lost all meaningful contact with friends and family that remained behind. Whatever real memories you did have of the place were subject to constant conditioning and adjustment - be it through the recitation of the facts in your own asylum application, or absorption of the stereotypes that already existed in the place where you arrived.

The fact that most emigrants of those times were refugees had, of course, a lot to do with it. The thoughts and desires of those wishing to emigrate fit in well with the geopolitical objectives of the Western Bloc during the Cold War: they were willing to keep telling everyone how awful the Soviet Union was. For many, this involvement in anti-Soviet propaganda, in some form, would become the only meaningful profession and enduring pastime in the West.

The nineties were a confusing time in the sociology of Russian migration. No longer refugees, the new country’s citizens started to travel - and come back. In order to stay in the West, they would now have to cope with elaborate and complex rules on professional and family immigration. Those who emigrated from Russia in the 90s, enabled by the easing of travel restrictions - or turned off by the post-Soviet chaos at home - were mostly professionals, or those who already had family members abroad.

No one took away their passports, residency registration - “propiska” - or property rights acquired during privatisation. Their bank accounts still worked and sometimes continued to accumulate trickling social payments. The Internet meant staying in touch with friends and family who could tell them what things were really like. They left behind a place they could easily come back to.

These factors changed the face of immigration for years to come. Many of us, who left Russia in the 1990s, still dwelled on the reinforcement of our reasons for doing so, but those reasons were no longer about hating the place we came from. They were more about the feeling that we were now in the “real” world. Having your kid play on a colorful playground or shop at Toys R US, seeing the abundance of choice in a local supermarket, watching cable TV, leasing a new “foreign” car, or going to Starbucks felt like a world worth being a part of, because Russia still didn’t have those things.

In the Putin years, the supermarkets, colorful playgrounds, Starbucks and cable TV quickly became even more abundant in Moscow than in the West. Very soon, you could watch CNN, get a latte, shop for groceries at 3 am, put cash into an ATM machine, drive a Volvo, or buy a new TV on credit. Consumer-driven emigration became pointless. On return visits, emigrants had started to discover that in Russia they were more likely to acquire a Volvo, or attain a social status needed in order to be able to afford one. Their language knowledge or western education or experience enhanced their Russian-baseed career prospects. Some found a niche in some market or other, others discovered that the family business had made it big, and so on.

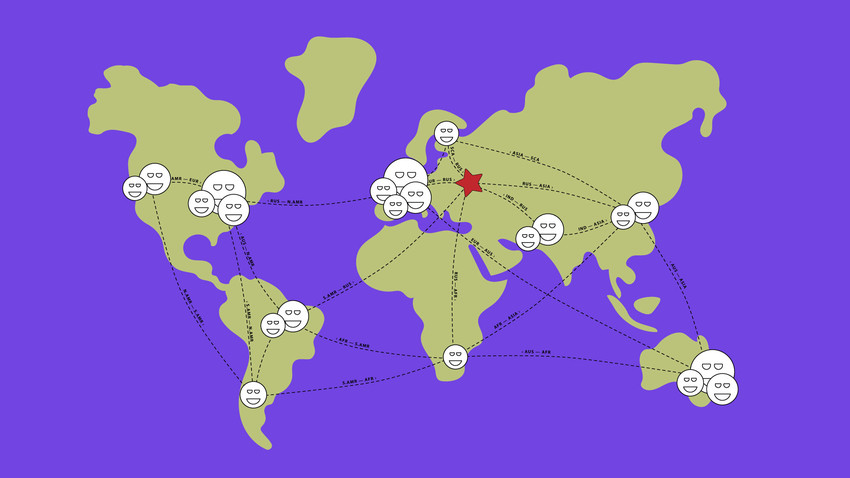

For the same reasons, many younger Russians, who were now able to travel extensively, often were unwilling to cut the cord. Russia now has an enormous number of people who have, in the past 20 years, visited dozens of different countries each. Many of them, drawing on the money from Russia-based remote jobs or a family business, have lived and bought property overseas - not just in the western countries, but also places like Goa or Montenegro. The Russians have become a global nation - they absorbed knowledge and understanding of not just the East and West as traditionally understood, but culture, economy, geography and life hacks of the whole world.

With such knowledge and understanding, any sort of migration becomes a useless label. The sort of “living” those Russians do in the West is often peripatetic - limited to a course of study, or a contract of employment, which can just as easily be followed by an endeavour back home, or in a different place. Many have dutifully followed the rules of an immigration program that led to naturalisation in a Western country, only to pocket the new passport and continue the journey. There are now Russians who hold citizenships of three or four different countries, and own homes in at least as many - not necessarily the same ones.

Russians today are a much more global nation than they were 20 years ago. Of course, this does not apply to all Russians - but it applies to those who would be emigrants otherwise. If they owe their very ability to travel and live abroad to the income and resources of their families or careers in Russia, it is not a place they are going to want to permanently leave behind.

It is also not a place they are willing to berate or belittle. While many of the ’global’ Russians are critical of the country’s government or customs in one way or another, they are increasingly less likely to share those inhibitions with anyone in the West. The same years of the Putin government that enabled their existence as global citizens, have also re-polarized the world in which they now find themselves. But the new wave of Russophobia no longer feeds off of the sentiments of immigrant Russians - instead, it targets them as representatives of their country of origin, often ignoring the fact that they are also citizens of the West.

Over the recent years, this process has led to a resurgence in Russian patriotism among Russians abroad, and an entrenchment of the global Russian diasporas in their right to be, and remain Russian. The Western propaganda has dusted off its old Cold War arsenal in the hope that it will work just as well against the modern Russia as it did against the Soviet Union - but it will soon run out of ideas and backfire. Unlike the refugees and refuseniks of the past, the Global Russians will not help maintain it.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox