“I feel good in my old man's fur coat, it’s as if you’re wearing your own house. They'll ask if it's cold outside today, and you don't know what to say, maybe it is, but how do I know?” – Osip Mandelstam wrote of a Russian shuba. Indeed, a good shuba helps to stay warm even in the harshest cold.

'Embassy of the Grand Duke of Moscow to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II in Regensburg,' 1576 etching. All Russian envoys in the picture a seen wearing posh shubas

Public domainThe very word “shuba” supposedly came into the Russian language from the Arab word jubba, where it means “a long-sleeved overcoat.” In Russia since ancient times, wearing a shuba has been a sign of wealth, because fur was always expensive, and to make even a knee-long shuba, a furrier needed 50-60 marten or silver fox pelts. What did ordinary people wear then? Coats made of sheep, or hare, animals much cheaper and easy to procure than marten, silver fox, or sable.

In Kievan Rus’, and in the Russian lands in general, before the Mongol-Tatar invasion of the 13th century, fur was used as money, and when exported to the Middle East and Europe, fur was exchanged for silver and gold, thus promoting the use of precious metal for minting coinage in Russia. After the Mongol-Tatar invasion, some of Russian lands paid Mongol-Tatar tributes in fur – for example, Novgorod region was made to pay in black sable.

A still from 'Mongol' movie, 2007. A Mongol military commander is seen in a kind of shuba

Sergey Bodrov-senior/STV, 2007High ranking Mongol commanders used Russian furs to make shubas and wore them as signs of wealth and power. Their shubas were worn in a peculiar manner. One shuba was worn with fur facing inside, for warmth, and another one, with fur facing outside, for show. Russian princes and then boyars borrowed this fashion of showing wealth, along with many other things they adopted from the Mongol-Tatars. Even the crowns of the Russian tsars were edged with fur, following the Mongol tradition.

A Russian boyar in a shuba. You can see the boyar is wearing a shuba with a turndown fur collar.

Konstantin MakovskyHowever, Russian princes, boyards, and generally wealthy people adopted the habit of wearing shubas with fur on the inside. They were shaped like a bell (expanding downwards), with wide sleeves and turndown fur collars. On the outer, ‘skin’ side, these overcoats were covered with expensive fabric, such as brocade, satin or velvet, embroidered with gold and precious stones.

Wealthy people sometimes wore several shubas at once – especially at festive occasions. As a ‘status clothing,’ shubas were even worn in summer! Imagine how those boyars sweated in their shubas and high fur hats in a stuffy room of a dusty wooden palace on a busy afternoon!

'An arrival of a voevoda' by Sergey Ivanov

Sergey IvanovPeter the Great got rid of the shubas in court in the 18th century – now, all courtiers, officials and military commanders were made to adopt European-style clothing. But in winter, they sure went back to the good old shubas, that just looked a bit different, without all the embroidery. But shubas were still worn with the fur facing inside – only simple folk wore them with the fur facing outwards, as we do now. Contemporary shuba in the 18th-19th centuries would suit a coachman or a peasant.

But everyone, no matter the class or denomination, suffered from omnipresent lice. Charles François Masson, a Frenchman in Russian service in the late 18th century, wrote: “When arriving to a ball, Russian ladies leave their magnificent black-and-brown, arctic fox, ermine, marten and sable fur coats to the footmen; while waiting for their mistresses, the footmen lie down on these fur coats. When the ladies are taking their leave, the footmen wrap them in precious furs, infested with parasites...” So, that was an additional price to pay for wearing a shuba. But that didn’t stop the ladies.

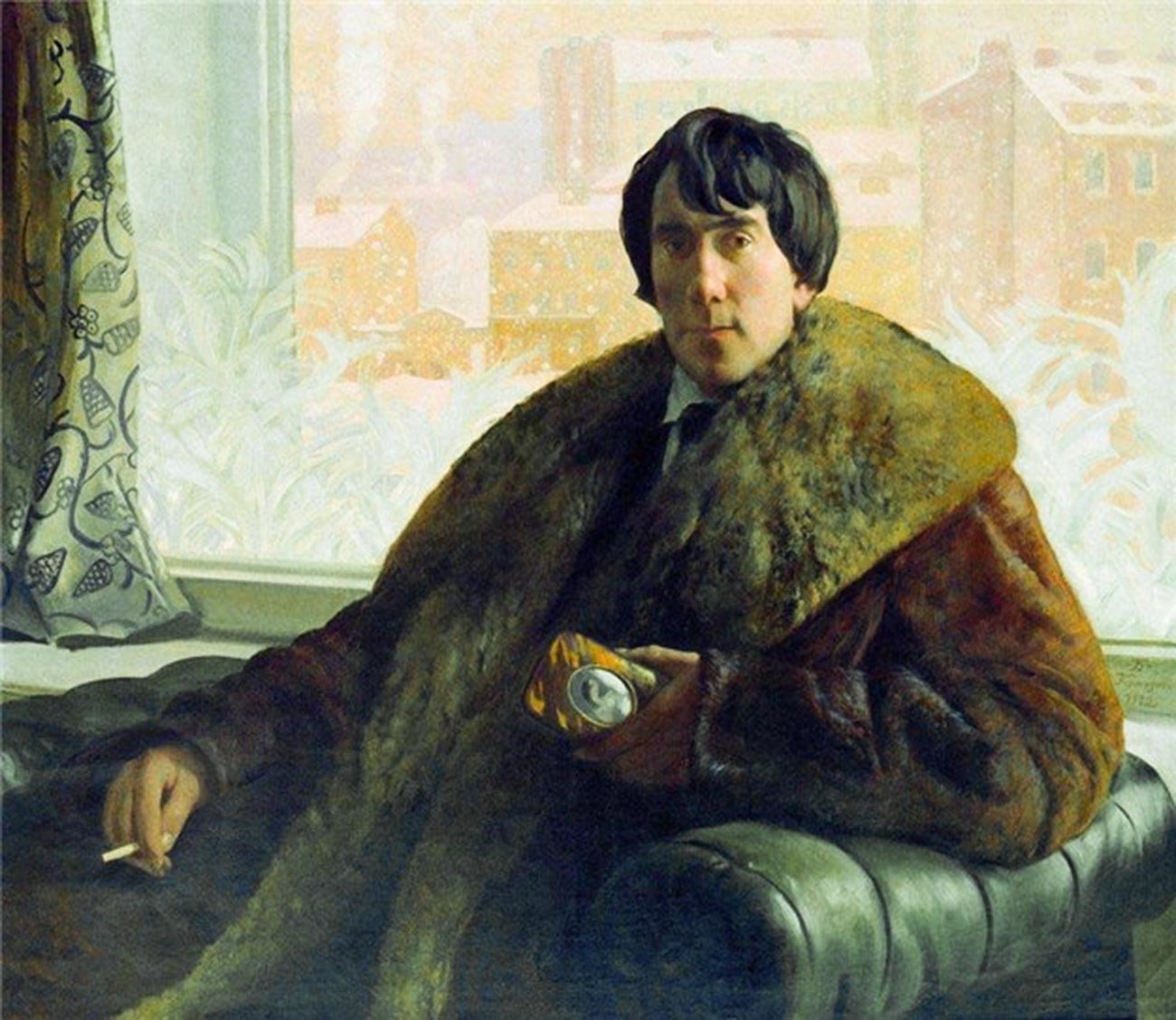

'Portrait of the sculptor and architect I. S. Zolotarevsky,' 1922, by Boris Kustodiev

Boris KustodievThere were certain rules for ladies wearing furs. As historian Julia Demidenko says, “There were hierarchic rules in the wearing of furs – not by class, but by age and social status. Women of senior age wear sable, and young girls – either Siberian squirrel, or Karakul sheep fur, or hare.” Young girls were obliged to wear cheap furs, even if their wealth allowed them to wear mink and sable – that was the custom. By the end of the 19th century, for girls and women it became trendy to wear shubas with the fur outside, to show the beauty of the fur.

In Russia, nobody would normally think of throwing out an old shuba. Even if it was worn and dusty, it could still be remodeled, or at least good parts of it could be used to make a hat or a collar for another shuba, because furs were always expensive.

The situation didn’t change much in Soviet times: a decent shuba could really cost a lot for a Soviet citizen, while fur exports - so important for the Russian economy - continued: in 1925-1926, the share of furs in Soviet exports was 89.6%. From the 1930s, fur production was monopolized by the state. On November 25, 1939, the government banned individual fur production and banned any individuals from trading furs – in order to protect domestic trade from profiteers.

A Soviet military intelligence officer, 1943, wearing a shuba

Sergey Shimanskiy/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruThe exports - and vast amounts of fur coats produced for the Red Army during WWII - Soviet Russia all but depleted reserves of fur-producing animals. In the 1960s, natural fur was still in short supply. Fur production managers complained that only a third of raw fur materials shipped to fur factories was of good quality. In 1958, Nikita Khrushchev actively advocated the introduction of artificial fur – an artificial fur ‘sheep’ shuba could cost 1,000 rubles (compared witht 4,000 rubles for natural sheep shuba). A cleaning lady’s salary in those years was 30 rubles a month, a seller in a department store made 100 rubles a month, a highly-skilled worker could make up to 200 rubles in a month. So for most people, a shuba cost a fortune.

However, artificial fur shubas had a major drawback – they were only half as warm as natural fur. So Soviet people still preferred natural fur, tried to procure ‘natural’ shubas, hats, overcoats by any means, and spent a lot of time looking after and repairing them.

About the contemporary Russian shubas, you can read our article: Why do Russian women still wear fur coats?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox