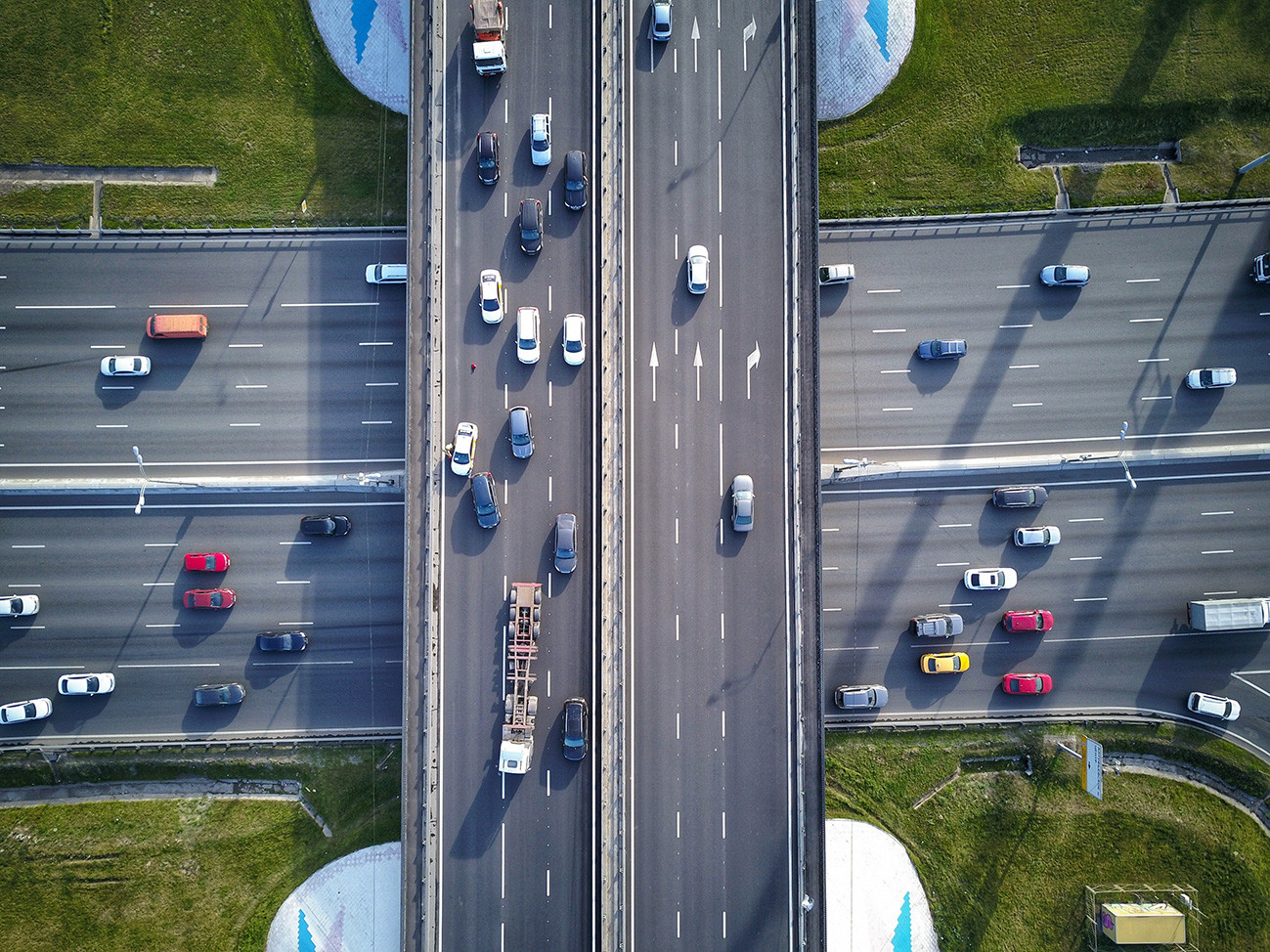

Cars slowly move along a bridge in traffic jam in central Moscow on March 6, 2020

AFP“The streets were deserted, like in some post-apocalyptic movie. It was especially creepy in the center of Moscow, where all life had completely stopped,” is how Moscow driver Ruslan Seregin describes the roads in Moscow during the coronavirus pandemic in the spring of 2020. Back then, motorists could only get around with a special digital pass in the form of a QR code, obtained in advance by specifying the purpose of the trip using a special app or website. For the first time ever, Seregin got to enjoy near empty roads in Moscow.

A traffic jam as police check IDs and passes of each person driving into Moscow at a checkpoint at the entrance to Moscow, Russia, Wednesday, April 15, 2020

APThis blissful state lasted from April 11 to June 1, 2020. With the lifting of the first lockdown restrictions, the number of vehicles on the streets soon approached pre-COVID levels and traffic jams that day jumped to a score of 6/10 on the Yandex traffic congestion scale.

At the end of 2020, Moscow and the surrounding region ranked first in the world by number of traffic jams, according to TomTom, a supplier of GPS navigation devices. Moscow has featured in the Top 10 cities with the largest traffic jams for the past decade, dropping to 13th place only once in 2015.

To combat traffic jams, every year Moscow builds new highways, roads and interchanges, as well as repairs and expands the old road network by at least 100 km annually, according to the website of the Moscow Urban Development and Construction Complex (MUDCC).

As a result, the share of congested road sections has decreased by 18% over the past ten years and the average travel time has decreased by nine minutes, according to the website.

From 2010 to 2020, more than 1,000 km of roads were built in Moscow, enough to relieve road congestion, stated Moscow Deputy Mayor Andrey Bochkarev in late 2020.

The final stage of the construction of the overpass between Yuzhnoportovaya Street and the 2nd Yuzhnoportovy Passage

Moscow Agency“Despite the number of cars increasing annually by 250–300 thousand, our total traffic volume did not rise and Moscow ceased to be a global traffic jam leader. So our efforts were not in vain,” Bochkarev said.

Nevertheless, the constant building and reconstruction of new roads has temporarily increased the number of traffic jams in certain areas of Moscow, say local residents.

“Around Medvedkovo District, where I live, a lot of interchanges are being rebuilt and wherever I try to go, I get stuck in a traffic jam. Before, it took me 40 minutes to get where I needed to be, but now it’s an hour and a half. Not like during the pandemic — I really miss those times,” says photographer Anton Ukhanov.

Thirty-six-year-old Muscovite Valeria Dashkevich has used public transport only once in the past five years. That was in early April 2021. As she explains, she encountered overcrowded trains in the subway and buses stuck on gridlocked streets.

“I thought I’d get there faster than by car, but because the road I needed was blocked and I had to change buses, it took even longer. My fear of public transport will last another five years,” says Dashkevich.

Electric bus

Kirill Zykov/Moscow AgencyThat said, the Moscow Department of Transport is actively developing the subway system: 56 new stations have been opened in Moscow since 2011, according to the MUDCC website. The new Big Circle Line is also being built. Set to consist of 31 stations, it should reduce any journey to 30 minutes, it is claimed on the same website.

In addition, a new overland rail transport line has appeared in Moscow — the Moscow Central Circle (MCC), plus new stations and services on existing commuter rail lines, known as the Moscow Central Diameters (MCD). The system is intended to help residents of Moscow Region to quickly reach and move around the city, hopping from one type of transport to another.

New routes are also being built for trams, buses, electric buses and trolleybuses — in Moscow there are more than 1,050 overland routes and more than 400 km of tram lines, reads the website of the mayor of Moscow.

A further 351 km of dedicated lanes for public transport have been built in Moscow. But, according to some Muscovites, they have not reduced the number of traffic jams at all.

Mask mode in Moscow on October 6, 2020

Alexander Avilov/Moscow Agency“I have a car with a permit to drive in bus lanes. I work as a cab driver. Recently, in a traffic jam, a man of retirement age ran up to me and asked for help — his wife was ill and he couldn’t get to the hospital,” recalls driver Ruslan Seregin. “The hospital wasn’t far, just a couple of miles away. But even using the bus lane, it took me about 30 minutes. Thank God, I drove the woman to the hospital and she was able to get treatment.”

Other Moscow residents still are afraid to use public transport for fear of contracting COVID-19.

“I used to take the subway to the center and to work and the car for trips outside the city. Now I go everywhere by car. I only use the subway when it’s not rush hour and even then I feel uncomfortable — too many people coughing all around,” says Muscovite Andrei Sobolev, 35.

In an attempt to rid the streets of “excess cars” and force Moscow residents to switch to public transport, the Mayor’s Office introduced a paid parking system back in 2012. The cost of parking varies from 40 to 380 rubles per hour (approx. $0.50–$5), depending on how busy the street is and the time spent using the parking lot.

Motorists face a fine of 5,000 rubles (approx. $65) for not paying for parking, and 3,000 rubles (approx. $39) for stopping in a public transport lane.

According to Moscow’s official parking website, in the first year that toll parking was introduced (that is, 2012–13), the average speed of traffic in the city increased by 12% and the number of cars using the Garden Ring Road (which encircles the heart of Moscow) fell by 25%.

Paid parking in Moscow

Sergey Kiselyov/Moscow AgencyBecause of the high likelihood of fines and expensive parking, some Moscow residents have switched permanently to public transport, but their decision was also influenced by traffic jams.

“After the pandemic, traffic jams increased several fold and expensive parking spaces in central Moscow are no good to me. So, now I use the car only to get to the nearest subway station and, from there, I travel the rest of the way to work. Lately, even the journey from home to the subway has been taking an hour, although without traffic jams it’s no more than 15 minutes away,” complains Anastasia, a resident of Podolsk, a city near Moscow.

In November 2020, Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin said that only fast public transport would motivate Muscovites to use their cars less and beat the traffic congestion problem.

“We already have millions of cars in Moscow and a million more get added every five years. There are so many cars there won’t be enough roads,” Sobyanin admitted.

Despite the growth in the number of private cars, the measures applied in Moscow to combat traffic are helping to slowly reduce the demand for private vehicles, according to Alexander Kulakov, director of the Center for Transport Modeling at the Faculty of Urban and Regional Development of the Higher School of Economics in Moscow.

A man crosses a street during a traffic jam on the embankment of the Moskva River in downtown Moscow

AP“The methods used in Moscow and the surrounding region do work, but they never show good results in a short time, especially in conditions that are not conducive to reducing the use of personal transport. To further combat traffic jams in the region, we need to continue working to improve the connectivity of the road network and develop a network of high-speed public transport,” says Kulakov.

Ilya Varlamov, a well-known blogger and urbanist in Russia, agrees on the need to develop public transport, yet he is against expanding the road network. In his view, new roads only encourage Muscovites to buy cars, thereby creating additional traffic jams.

As he sees it, the primary cause of road congestion is drivers who violate the traffic rules, resulting in accidents and snarl-ups.

“You can build 100 new state-of-the-art highways, but if some f*ckers continue to break the rules, the jams will remain. There’s no proper driving culture in this country. <...> What to do with these f*ckers? <...> The only thing is to increase the fines for reckless behavior. <…> 5,000–10,000 rubles [$65–130]!” writes Varlamov on Instagram.

According to Alexander Shumsky, head of the Probok.Net expert center, Moscow topped the traffic congestion rating only because it was the first in the world to come out of lockdown. That said, measures are still needed to tackle the problem.

“We need to reduce the demand for private vehicles. That is the next stage of transport development that we have to complete. We have introduced toll-only parking, but there is no charge to drive into Moscow or certain areas of the city and no restrictions or tariffs based on the green classification of vehicles or regions,” explains Shumsky.

Nonetheless, the Telegram account of the Moscow Department of Transport also stated that road congestion in 2020 was down by 5%, year on year, and the mere fact of traffic jams during the pandemic is not a negative indicator.

Cars are stuck in a traffic jam on a bank of the Moskva River outside the Kremlin, with the Christ the Savior Cathedral, left, in the background, in Moscow, Russia

AP“Moscow is the global leader in terms of traffic jams, but this time that’s a good thing. It always seemed like traffic congestion was a bad indicator. But in COVID-hit 2020, the opposite can be said to hold true. It means the city did not put life on pause <...> roads were open and public transport, albeit with severe restrictions, continued to operate,” wrote the department.

Russia Beyond sent a request for comment to the Moscow Department of Transport, but had not received a response at the time of publication.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox