“The consciousness becomes confused, there are frightening hallucinations: the afflicted sees the devil, a scary man or something of the sort; she begins to scream, sings, rhythmically hitting her head against a wall, or swinging it from side to side, tearing her hair out.”

This is how a typical episode of this peculiar disease was described in the early 20th century by doctor Sergey Mitskevich, after examining a Yakut woman. This culture-bound syndrome became translated into Russian as miryachenye - from the verb miryachit’ - being overcome, or being in a state of total submission. The word is a Russian bastardization of the Yakut word Menerik - with various terms across the northern hemisphere (and beyond) describing essentially the same trance-like, disoriented condition. The choice of word is arbitrary and dependent largely upon what Arctic culture one is referring to. Russians, meanwhile, began to encounter the condition in the early 19th century, noticing that only people in the north were afflicted with these sudden states. Sometimes, they affected individuals, at other times - entire groups.

The symptoms were very similar across the board: the person suddenly found themselves completely detached from physical reality, entering into a virtual trance state; episodes were accompanied by tremors and spasms. Ethnographer Vaclav Seroshevsky observed very powerful physical and mental anguish that would befall them. “The sufferer wails, shouts, snivels, tells incredible tales, while also breaking down and being thrown about the place, until, completely drained, they fall asleep.”

The episodes are marked by the person repeating the words and actions of those around them, becoming extremely susceptible to external control, even when the commands given are dangerous and/or nonsensical. “If someone in the presence of the sufferer were to jump or hit themselves, they would do the same; they can smash a dearly valued item, or even let go of a baby in their arms, if someone in front of them were to perform the action of throwing,” researchers would note. Meanwhile, if one were to try and limit the actions of the afflicted person, they would sink into a raucous state, demonstrating unusual physical strength. There is plenty of evidence of cases where several adult men would not be able to restrain a teenager during an episode.

Lapland expedition A. V. Barchenko (1922)

Public domainHowever strange, while some episodes could be chalked up to temporary confusion, insanity or a prank, when an entire group of 70 people experienced the condition, researchers had serious reason to suspect that something much more worrying was at play. In 1870, a case was registered among the Cossacks of the Nizhne-Kolymsky unit in the midst of doing drills. The company suddenly began repeating their instructor’s commands, as though they were parroting him for fun. The commander was incensed and quickly became angry, then was taken aback by his own threats being repeated right back at him by his soldiers. The company then all simultaneously dropped their rifles.

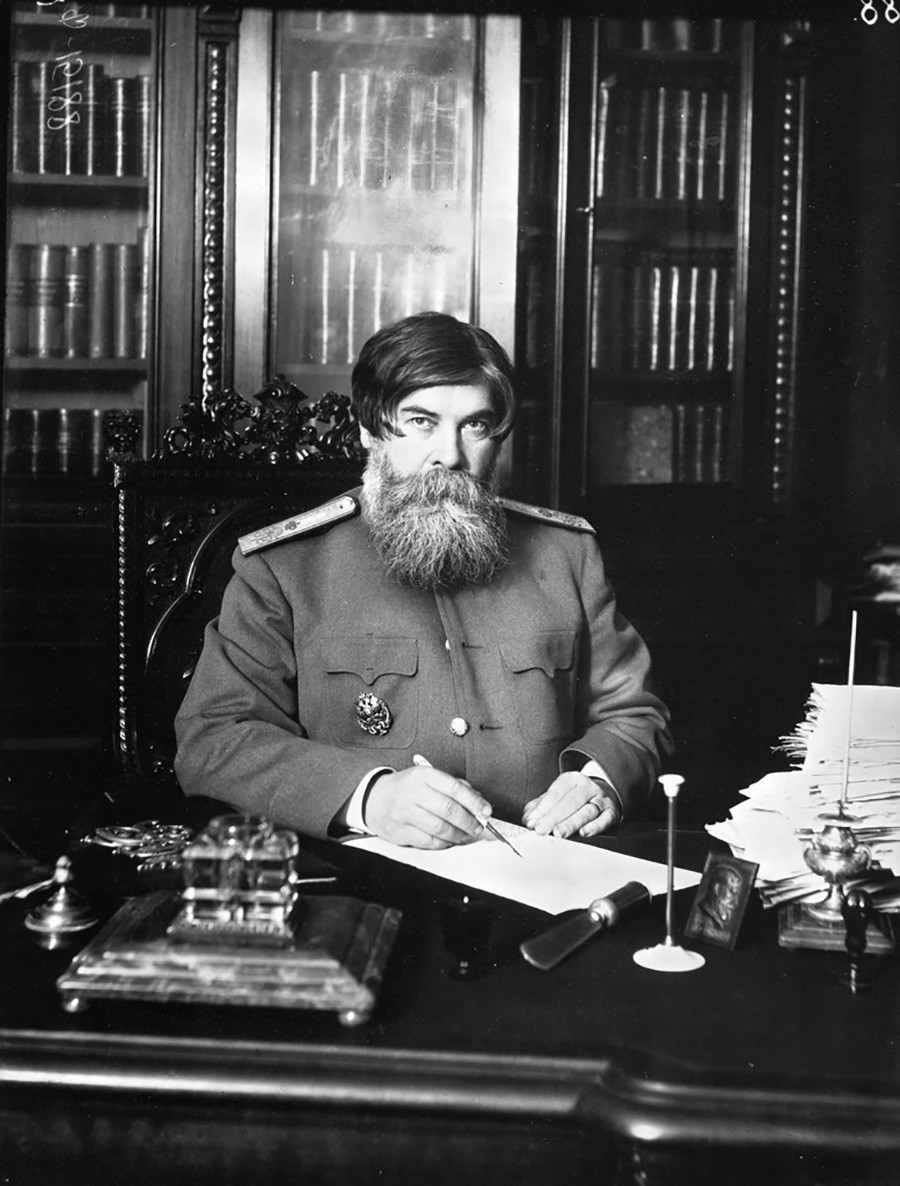

Serious research on the menerik was not conducted until 1922. There was already plenty of evidence of the phenomenon by then. Psychiatrist and researcher Vladimir Bekhterev took an interest after receiving word from a doctor and former exile in the district of Lovozero, on the Kola Peninsula. Having observed spontaneous episodes of the sickness as they took place in neighboring communities as well, the doctor finally drew the connection with instances of aurora borealis - Northern Lights, which earned it the nickname ‘The Call of the Polar Star’. Menerik was the result of external natural occurrences, according to the doctor (only known by his last name - Grigoryev).

Vladimir Bekhterev

Public domainBekhterev founded and headed the Institute of the Human Brain, which, aside from studying physiology and psychiatry, also searched for scientific explanations to things like telepathy, telekinesis and hypnosis. He traveled to the Kola Peninsula with a party, headed by Aleksandr Barchenko - a prominent esotericist and researcher. In reality, the main objective of the expedition wasn’t the study of a polar psychosis, but the hunt for the remnants of a mythological hyperboreal civilization (one the Nazis had previously searched for, believing it to be the progenitor of the Aryan race). However, Soviet intelligence took a special interest in menerik, with VChK chairman Felix Dzerzhinsky personally supporting the idea. So, when Barchenko arrived on the scene, he would spend the next two years rigorously studying and collecting data on the sickness - even falling prey to it himself.

А. V. Barchenko (upper left) with the expedition at the "sacred" Lopar underground cave at Lake Lovozero. 1922.

Public domainAround Lovozero, he attempted to get local shamans to let the expedition through to the sacred island of Rogovoy. Having been denied, the group went anyway. While on their journey, near Seydozero lake, they began encountering smoothed-out rectangular granite rocks, reminiscent of pyramids, as well as what looked like remnants of paved roads, followed by a strange path that led underground. The group didn’t manage to get inside, however. According to their testimony, everyone was suddenly struck by an inexplicable feeling of sheer terror - they’d all lost control of their emotions.

The Lapland Expedition of A. V. Barchenko

Public domainUpon return, Barchenko presented a closed report on the phenomenon, but the reasons for its occurrence remained a complete mystery. The report was classified. Modern researchers later tried to research it through FSB archives, but were told that all the data was completely destroyed in 1941, when Nazi forces were on approach to Moscow. Barchenko, meanwhile, was accused of spying for Britain, as well as creating a Masonic counter-revolutionary organization and was executed by firing squad on the very same day - April 25, 1938. Other participants of the group also faced Stalin’s repressions in the late 1930s.

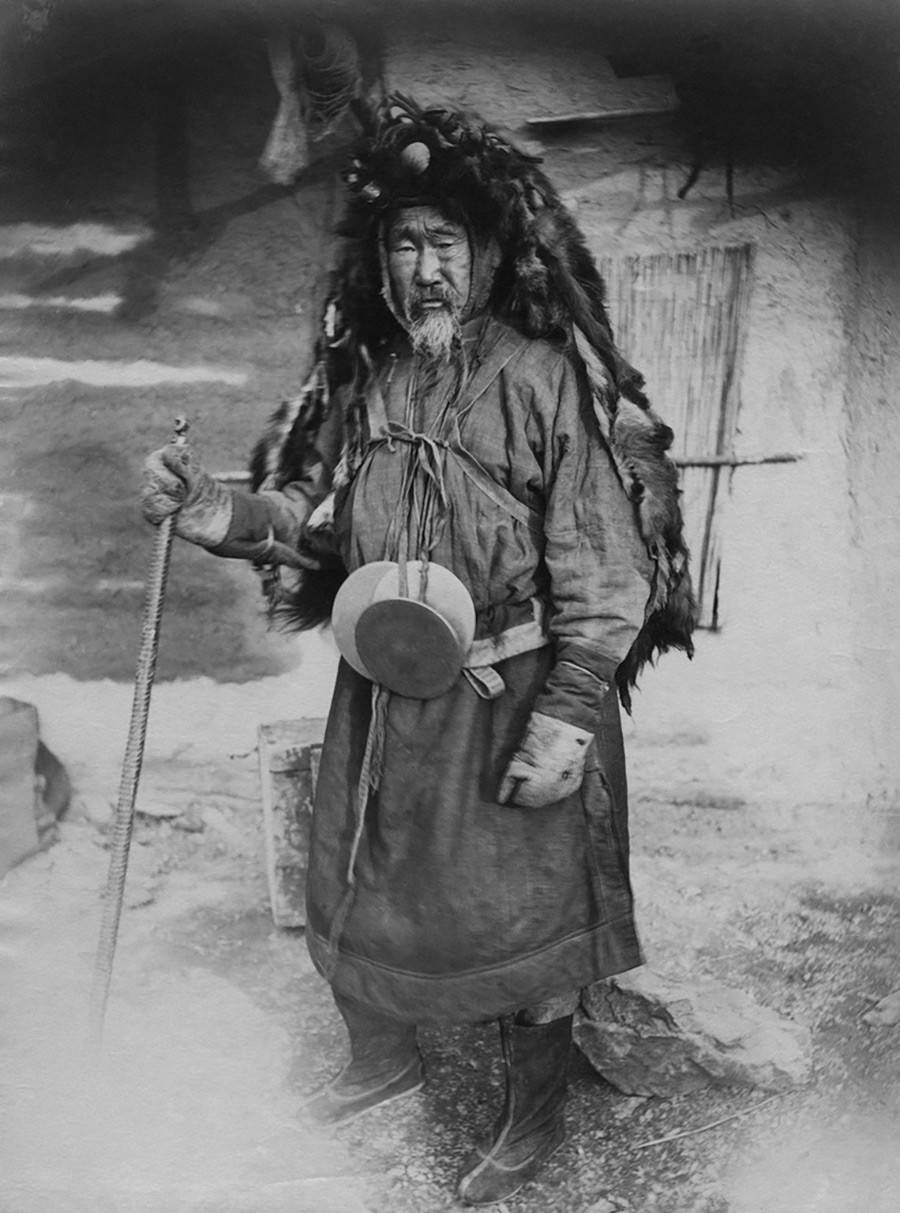

Northerners believe menerik to be the harbinger of the so-called “shaman’s sickness”, owing to the similarities in how people act during spiritual seances. Both phenomena are explained by spirit possession; however, if the shaman invokes the presence of the spirit at will, those afflicted with menerik have no choice in the matter.

Shaman. Date of shooting: 1900s

В. Soldatov / Union of Russian PhotographersPsychiatrists have drawn similar parallels, but believe the root of both conditions is hidden in the northern peoples’ increased malleability to psychotic epidemics. “The concentration of a large number of persons sharing similar traits of heightened malleability created in the native societies of the North and Siberia a particular psychological climate, conducive to a heightened sensitivity to the cultural meaning of shamanism. It’s no accident that the death of a shaman frequently led to a spark in psychogenic illnesses,” scientists note. “The epidemic would usually stop as soon as one of the sick became a shaman.”

Researchers point to similarities in these expressions of hysteria witnessed among other indigenous peoples: there is latah among the Malay, jumping among the Native Americans, imu among the Ainu and so on; and a number of parallels can be drawn with screaming types of hysteria that incorporate additional religious connotations: the screamers cannot stand to be around Christian symbolism - be it objects or rituals, prayer and the inability to perform a sacrament.

This specific psychological constitution was not borne out of nothing, scientists believe. Lovozero, which the Soviet expedition visited on its research trip, is located smack in the middle of the Kola Peninsula. There is tundra and swampy taiga for miles around, with the occasional volcano. The place experiences winter for most of the year. And the polar night - the period when the sun does not reappear in the sky - lasts an entire month. The polar day (the opposite), meanwhile, lasts 52 days. All of that increases the strain on the nervous system and has a negative effect on a person’s health. Psychiatrist and ethnographer Pavel Yakobi wrote that the psychogenic epidemic “develops only in an exhausted, weakened people - physically, culturally and mentally”.

Skin primer in a camp of lapps

Legion MediaEthnographer Vasily Anuchy recalled stories of political exile to Turkhansky Region (an area in Eastern Siberia, today Krasnoyarsk Region). The punishment was in wide use in 1905, after the first Russian Revolution. “The exiled would often complain of insomnia, migraines, heart palpitations, stomach pains, visual and auditory hallucinations, irritability and hospital in Tomsk a mere year later,” he wrote, noting that the practice would later be banned by the government, owing to its “excessive cruelty” (the Soviets would resume it later).

Northern lights

Bettmann/Getty ImagesPsychotic episodes coinciding with Northern Lights can be linked with the organism’s ability to react to changes in the magnetic field (the brightest Northern Lights usually happen during magnetic storms). It’s no accident that northern shamans often time their rituals to coincide with the natural phenomenon. It would seem then that menerik can be explained by a combination of climatic, socio-cultural and physio-geographical. Especially as it wasn’t only the local that got sick, but outsiders as well, after spending a substantial amount of time there.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox