If we were to briefly describe what February 23 means for people in Russia, we would say: It’s the male equivalent of International Women’s Day. Only, unlike March 8, which was imported from the West, February 23 is an entirely Russian invention.

Over many years, the date has repeatedly changed in significance and, in the end, it has mutated into one of the two gender-based holidays (the other one, as you can guess, is International Women’s Day). In the same way as March 8 is associated for a vast majority of people in Russia with flowers, candy and gift vouchers from a cosmetics store rather than the struggle for equality, in the popular imagination, February 23 goes hand in hand with socks and shaving cream… But how did it come to this?

February 23 became a holiday under the Soviet authorities - it was they who invented it. It was marked for the first time in 1919. There were several reasons for it.

On January 28, 1918, the Soviets passed a decree on the formation of their own army. Two weeks later, on February 11, they issued a decree creating the navy. The new authorities regarded both events as of great significance and their first anniversary was expected to be celebrated, but, owing to bureaucratic delays, the Bolsheviks didn’t manage to declare the holiday in time. Also, a charity event was planned for February 17, 1919, when, as conceived by the Bolsheviks, members of the public were supposed to donate gifts to Red Army soldiers. The event was dubbed ‘Red Gift Day’. But it fell on an inappropriate day - a Monday. It was then decided to celebrate all three events on the same day on the nearest Sunday, which was February 23.

The first military parade on Palace Square during the celebration of the anniversary of the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army. February 23, 1919.

TASSThe fifth anniversary was celebrated on a grand scale and nationwide. And not on January 28 or February 11 - the actual days of the signing of the decrees - but on February 23, just as it had been the first time round. The holiday was given a new official name - ‘Red Army and Navy Day’. According to historians, at this point, attempts began to be made to invent some event to justify its celebration on February 23.

In the same year, the ‘Voennaya Mysl i Revolyutsiya’ (“Military Thought and Revolution”) journal claimed that the first Red Army unit to take part in fighting on the Northwestern Front (in World War I) was formed on February 23.

Red Army Oath, 1918-1919

Yakov Steinberg / MAMM / MDF / Russia in photoThe following year, the ‘Voyenny Vestnik’ (“Military Bulletin”) published a photocopy of Lenin’s decree on the establishment of the Red Army, but this time with the false date of February 23.

And in the second half of the 1930s, another theory grew legs: It alleged that a decisive battle between the newly-formed Red Army and German troops had taken place near Pskov and Narva on February 23, 1918, in which the Reds won their first victory.

The Red-Banner Baltic Fleet

SputnikIn the post-Stalin period, however, it turned out that, according to archival records, the German Army was 55 km from Pskov and 170 km from Narva on the day in question. Some historians, in particular Sergey Nayda, believe that no significant battles took place at that time at all and that the reason for the holiday were the rallies in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) and the mass enlistment of volunteers into the Red Army after the publication of Lenin’s appeal, “The Socialist Fatherland is in Danger!”, in response to the German advance. Others, for example historian Vadim Erlichman, suggest that it could relate to 300 Latvian riflemen who tried to repulse the Germans in the town of Valka. The only trouble was that, according to the archives, they were not victorious at all.

Participants of a ski tour along the Moscow-Pskov-Narva-Moscow route with ampoules of earth from the places where the Red Army's first victories were won. 1968

Budan Victor, Savostyanov Vladimir /TASSThis idea - that, at the dawn of its existence, Red Army detachments were of no great use - is supported by the words of Lenin himself: In an article in ‘Pravda’ newspaper on February 25, 1918, titled ‘A Hard, But Necessary Lesson’, he wrote: “There have been painful and shameful reports of regiments refusing to retain their positions, of refusing to defend even the Narva Line and of failing to carry out the order to destroy anything and everything in the event of retreat, not to mention the desertion, chaos, ineptitude, helplessness and disorderliness… The Soviet Republic has no army.”

Sailors and officers in the parade ranks during the celebration of Soviet Army and Navy Day in 1964.

TASSOfficial ideology, however, continued to adhere to the story of “victory at Pskov and Narva”. The matter was settled by Joseph Stalin in his order of February 23, 1942. “Young Red Army detachments, which had joined the war for the first time, delivered a drubbing to the German invaders at Pskov and Narva on February 23, 1918. This is why February 23, 1918, has been declared the birth date of the Red Army,” it said.

The story of the “victory at Narva and Pskov” was maintained for many years by USSR state propaganda. It became traditional to hold a formal session of the party and to organize celebrations in army units, at factories, at higher educational establishments and in schools to mark the day.

During a demonstration on Palace Square.

Adamovich Nikolai, Berketov Nikolai, Yevdokimov Vyacheslav /TASSAnniversaries were marked by the opening of museums and exhibitions and by military-sporting competitions for school children.

February 23 became particularly relevant in the wake of World War II, when patriotism was elevated to a high pitch. In 1946, the holiday was renamed again: Instead of ‘Red Army and Navy Day’, it became ‘Soviet Army and Navy Day’. This was the name it had until 1991.

After the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the holiday acquired its present name: ‘Defender of the Fatherland Day’. And, whereas previously it was a working day for all Soviet citizens (except servicemen), since 2002, it has been a public holiday for everyone.

The exhibition of weapons was shown to schoolchildren.

Evgeny Yepanchintsev/TASSSimultaneously, its significance has been eroding. February 23 is beginning to be regarded as a celebration for all men without exception, irrespective of whether they have been in the military or served in the army at any point. At the same time, the military theme in the form of camouflage apparel and military songs is still popular when the day is marked.

Along similar lines to International Women’s Day on March 8, it is also customary in Russia to give small presents on March 23 - to all men. The tradition is widespread in families, at schools and factories and, particularly, in offices.

In the run-up to each February 23, the female part of the workforce secretly hatches a plan on how to mark the day and what presents to give the men and phrases referring to the “stronger sex” and “strength and courage” and other attributes of masculinity form part of their wishes and greetings. Many people try to think up original ways of marking the day.

"After February 23..."

“At work, we were greeted in the morning by the girls, dressed in multicolored dresses, who handed out colas and hamburgers and took photos. They then walked around in tight-fitting trousers and white shirts, wearing ties and carrying pistols, setting us tasks (my treat was a kiss from all the girls, while a guy had to lift one up ten times!) and distributed ‘funeral urns’' - thermal mugs with the company logo,” recalls ‘SnakeAiz’ online.

“We got shower caps from the girls - some in the form of aviator’s helmets and others modeled on military side caps. Then, they laid out a table spread and put 4,500 rubles a head on our bank cards,” says Technar.

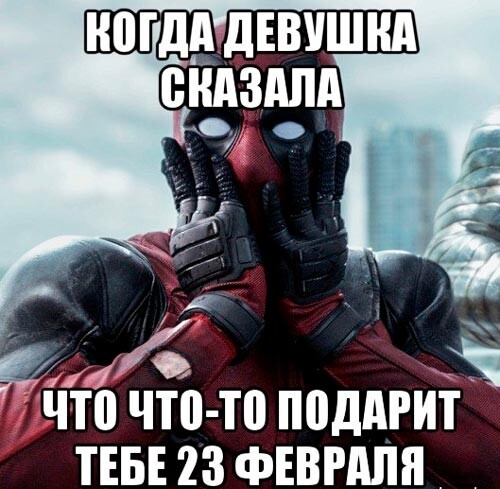

"When a girlfriend said she was getting me something for February 23"

At the same time, the day is much more frequently marked on a tight budget (because each member of staff, as a rule, pays for the presents out of their own pocket), so many people give only small gifts. Topping the list are pens, mugs, socks, shower gel, notepads, calendars and… yes, shaving cream.

This last item has pretty much become the embodiment of the standard February 23 present.

Each year, according to opinion polls, socks and shaving accessories are named among the most unwelcome gifts, but here and there in Russia, shaving cream and razors are still sold out before each February 23 and tongue-in-cheek selections of the best shaving cream to suit all budgets are published in the media.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox