Chewing gum met the fate of many other things that did not fit the Soviet notion of what was right. It was not officially banned, but it was frowned upon.

The rubber candy became a real “forbidden fruit” for Soviet children and teenagers. They were eager to possess it and were willing to do anything for it. Some even begged foreigners for chewing gum, risking the attention of law enforcement.

Up until the 1970s, the USSR did not produce chewing gum. Only a handful of people who had been abroad knew about it and had tried it: diplomatic staff and their families, the nomenklatura, translators, etc. But the average Soviet citizen was unfamiliar with it. Chewing gum, however, was condemned by Soviet ideologists as a reflection of the meaninglessness of the capitalist system and a symbol of the hostile American culture.

With the weakening of the Iron Curtain after Stalin’s death, elements of Western culture gradually began to penetrate Soviet reality. In 1955, Soviet citizens even had the opportunity to travel abroad. Very few had this opportunity and travel was subject to many conditions: impeccable reputation, recommendations, filling out an exhaustive five-page questionnaire with personal information and even a medical certificate.

May 1st, 1969. Soviet tourists in Versailles.

Vladimir Voytenko/TASSArt historian Mikhail Herman later recounted: “I got a medical certificate as a payola. Even the healthy ones were given one very reluctantly. One could be fit for military service, <…> but not fit for a trip abroad.” However, even when going abroad, a Soviet person had the right to take a rather limited amount of money with him and exchange it for currency. Everyone tried to use it to buy something significant, anything from clothing or equipment, and there was not much left over for chewing gum or other small things, so they did not bring it in such large quantities.

It is not known exactly when chewing gum first came to the Soviet Union on a mass scale. Probably the first wave of popularity is associated with the VI World Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow in 1957. There were many foreign visitors to the capital, who sometimes gave chewing gum as a souvenir and received Soviet trinkets, such as badges, in return. If a friendly exchange turned into a commercial action, it was already called ‘fartsovka’ - buy-sell or barter with foreigners. That’s how before and after the festival, a fair amount of Western household items made their way into the USSR. ‘Fartsovka’ dealers could be detained for speculation or foreign currency transactions, but that did not stop the Soviet youth.

July 31st, 1957. Electrician from Finland shows soviet kids his badges.

Yevgeny Yasenov/TASSThe next “gum boom” happened during the 1980 Olympics in Moscow.

The atmosphere before it was quite tense, as the capitalist powers boycotted it and the Soviet authorities did not rule out possible sabotage. Free entry to Moscow was closed and children were also advised to leave the city, because it was summer vacation. However, authorities still felt it necessary to urge the residents remaining in the city to be vigilant.

Closing ceremony of 1980 Olympics.

МАММ / МДФ/Russia in photoNow, it is difficult to establish the original source of the rumors, but a rumor began to spread through the cities where the competitions were held, that police officers allegedly were going to some schools and factories and warning that it was dangerous to make contact with a foreigner and that foreign gum might be poisoned or even filled with razor blades. There was talk of some schoolboy who had accepted such a “gift” and ended up in the hospital. The point was also made that accepting any gift meant “worshiping the West” and that the person accepting the gift was just a few steps away from being recruited by foreign intelligence.

Among young people, however, there were those on whom all threats and prohibitions had no effect. For many, chewing gum became a symbol of colorful Western life, appealing and inaccessible. Moreover, a rare commodity raised one’s status among peers: in an interview with ‘Pionerskaya Pravda’ newspaper, a schoolboy in the late 1970s confessed that, among other things, he needed chewing gum because he loved to be asked for some.

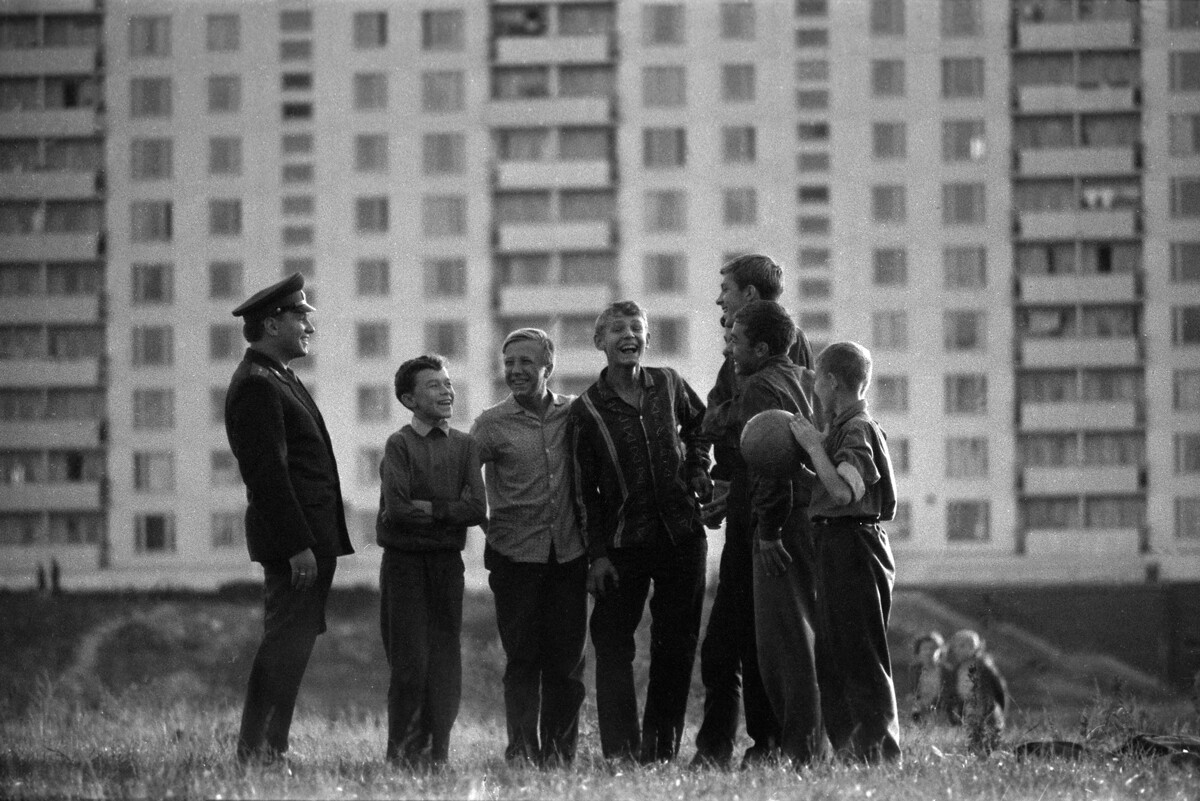

Sublieutenant Ivan Sizonenko with boys, 1967.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/SputnikThe USSR began to produce its own gum after the tragic events of 1975 in the Sokolniki Stadium in Moscow, where the youth hockey teams of the USSR and Canada were playing. The Canadian team was sponsored by Wrigley’s chewing gum, which some of the fans were waiting for at the game. After the game ended, Soviet spectators rushed to the exit of the stadium behind which the Canadian buses were located. However, the exit was blocked and the stadium lights suddenly switched off. According to one version, they turned off the lights on purpose, so that foreign journalists could not film the rush of Soviet teenagers around the chewing gum. Because of the blocked doors and darkness, a jam occurred in which 21 people died. Thirteen of the victims were under 16 years of age.

After the incident in Sokolniki, the first Soviet chewing gum production began in 1977 in Yerevan (Armenian SSR). This was followed by the production of chewing gum at one of the largest Soviet confectionary companies - ‘Rot Front’. Strawberry, orange, mint and coffee chewing gum appeared on the shelves in packages with five pieces each.

Soviet gum.

amgum.ruUp until the collapse of the USSR, chewing gum remained the subject of speculation, but along with the advent of its mass production, excitement around the once-desirable attribute of Western life began to wane. In the 1990s, when imported goods flooded the Russian market, foreign chewing gum quickly replaced Soviet chewing gum and children and teenagers had a new object of exchange and even collect - inserts with pictures from the ‘Turbo’ chewing gum brand. “The value was not in the gum itself - after five minutes, it was completely tasteless. Inside the chewing gum were inserts with pictures of cars and motorcycles, with which all the boys used to learn about the foreign car industry. On the streets, there were only Volgas and Zhigulis, but, on the inserts, you could find everything from Lamborghini and Bugatti to Opel and Toyota,” recalls Arthur, who collected these inserts in the 1990s. They even invented a game with the inserts: they put two inserts on top of each other, curving them slightly upwards on the edges and hit them with their palm; if the inserts flipped over (the paper was very light), then the player would get both. There were several hundred different inserts in ‘Turbo’ chewing gum and many teens wanted to build a collection, so, sometimes, the pictures became stakes in other games.

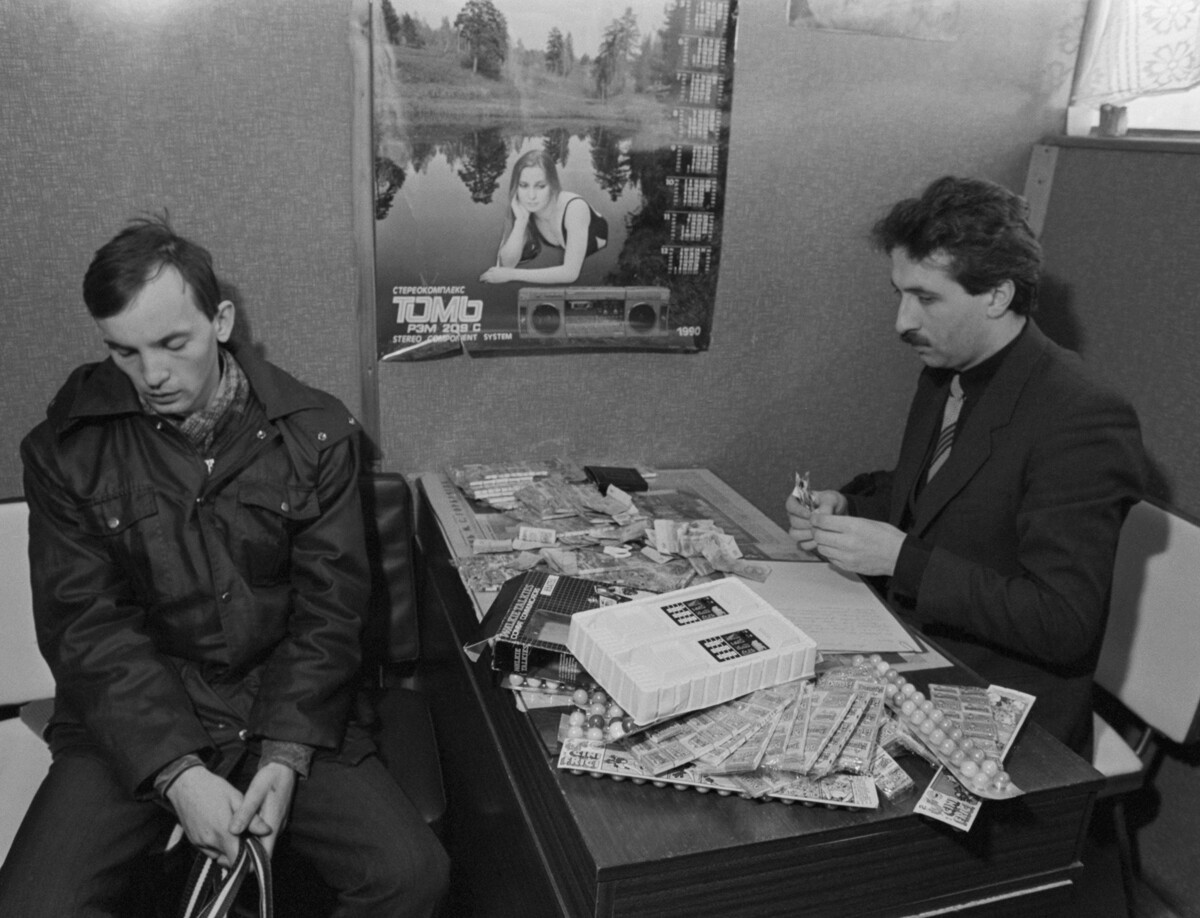

June, 1st. A seller of foreign bubblegum at the police station.

Vladimir Kazantsev/TASSDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox